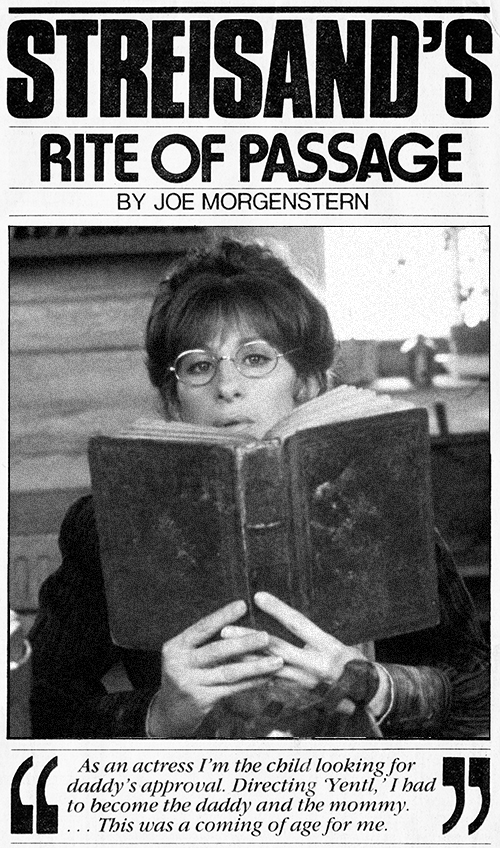

Streisand's Rite of Passage

Los Angeles Herald-Examiner

Sunday, November 13, 1983

One night when I was still living on Central Park West in New York, my extremely upstairs neighbor Barbra Streisand, who lived on the 21st floor in the penthouse once occupied by Lorenz Hart, called to ask a favor. A man named Valentine Sherry had just brought her a short story he thought would make a good movie. She wondered if I would read it and tell her what I thought.

The story was Isaac Bashevis Singer's “Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy.” I read it and was enchanted by its intricate and funny account of a young girl in an Eastern European shtetl who passes herself off as a boy so she can study the Talmud, then falls in love with a male student. I called Barbra back and told her what I thought, that she should grab it and make it her next movie.

I would like to be able to report that my neighbor, acting solely on the basis of my ineffable wisdom, grabbed the story and made it her next movie. That's not the way it worked, though. The night she called me was at least 15 years ago — neither of us can pin it down more precisely — and I was only the first of many people whose advice and support she solicited on “Yentl” ’s long and difficult journey to the screen.

Why was it so long and difficult? “Because nothing to me is ever right or good enough,” Barbra said when we talked about it recently. That’s shorthand for perfectionism, of course, a blessed curse to which she's never been a complete stranger. But there were other reasons for her plunging slowly on this one.

Unlike most movie projects presented for her approval, “Yentl” began with the original short story and nothing more. It hadn’t been pre-tested on Broadway, like “Funny Girl,” “Hello, Dolly!” or “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.” It didn't have a script, like “The Owl and the Pussycat,” or even a treatment, like “The Way We Were.”

“On ‘The Way We Were,’” Barbra said, “l knew what I'd do right away because there was a 50-page treatment with five great scenes in it. As soon as l finished reading the treatment I called Ray Stark and said: ‘I want this to be my next movie.’ ”

For all its shimmering promise of beauty and humor, the Singer short story presented some formidable practical problems, like how to play an 18-year-old convincingly when your audience knows you’re close to 30 (Ivan Passer thought she was too old as well as too famous for the part when he was supposed to direct it in the late 1960s); how to convince studio chiefs you can direct it yourself, and how to secure major financing for an unclassifiable period piece about love of learning and Jewish boys and girls together at the turn of the 20th century.

Four or five years ago, when Barbra was in her mid-30s and “Yentl” seemed no closer to production than ever, I heard her discussing it with the late Paddy Chayefsky and wondered whether she was going to talk poor “Yentl” to death rather that shoot it, or play the part from a wheelchair, like Sarah Bernhardt, and become the oldest 18-year-old in history.

What I didn’t understand until I saw the movie, with its splendid performances, rich textures and accomplished, adventurous direction, was that Barbra wasn‘t just talking all those years, she was learning. Barbra is a ferocious learner. She collects knowledge with the intensity of a bag lady collecting string, then weaves it secretly, sometimes subconsciously, into fabrics of her own design.

She solved the age problem partly by looking young — astonishingly young, considering that she was working both sides of the camera and waiting till the end of the day to shoot many of her own scenes — and by making Yentl ageless, neither young nor old but a rebellious girl-woman who’s ahead of her time: in other words, a shtetl version of Streisand breaking out of Brooklyn.

She brought music to the story, over the strenuous objections of Singer himself, and used it ingeniously to enhance the drama. And in her work as director, she took the deepest plunge of her life. Instead of making one of those sensitively performed but static and essentially miniaturized feature films that movie actors often turn out as their directorial debuts, she made a bold movie, full of surprising choices and a delight in the medium’s possibilities. (One deliciously choreographed dinner sequence ranks right up there with the great eating scenes of movie history.) Whatever “Yentl” ’s faults may be, caution and timidity are not among them.

“I don't think I'd like to be a director and have that big responsibility of telling people what to do, especially actors, because I hate dealing with egos. And yet I have a feeling about how things should be photographed, how they should look. I'll see something with it darker, or with it lighter, or using a rim light, or just using a source light from over here. .. ”

Barbra told me that in 1969, after she'd done “Funny Girl” and “Hello, Dolly!” and I was writing a cover story about her for Newsweek. She laughed when l exhumed the cassette a few weeks ago, but she also shrugged the resigned shrug of someone who’s just been reminded of something she has known about herself all along. “l think l've always thought like a director,” she said, “and people have either liked me or not liked me for it. As an actress I'm the child looking for daddy’s approval. Yet the child is a very opinionated child. Directing ‘Yentl,’ I had to become the daddy and the mommy. l couldn’t be the child any more. I had to be my own father, and everybody else’s mother. At times I missed wanting to impress my dad, but this was a time of really growing up for me. This was a coming of age for me, becoming an adult. I can no longer call someone and say ‘Rescue me, help me, I need to be taken care of.’ I like the feeling of being taken care of, but I also know I can take care of myself.”

“Basic ideas, principles never change,” she also said in 1969. “That’s why nobody can ever really change. People who are bastards now were bastards then, people who are nice now were nice then. There's no such thing, I don‘t think, as success changing somebody ...”

Success hasn‘t changed her all that much, though the trappings have certainly grown progressively heavy. She still wonders about those trappings: the house in town, the ranch in Malibu, the furniture and the Art Deco treasures. “I lived with my mother who had newspapers on the floor so it shouldn’t get dirty, and crappy plastic covers on the furniture so it wouldn’t get stained. Where’d I get this appreciation for fine things? I don’t know. I just got it.”

She’s still preoccupied by the same things that preoccupied her then: getting it right (“I’m a detail freak, but I don't drive actors to do take after take until they're exhausted. I’m willing to compromise on technical things if the performance is there”), getting it really right once she’s gotten it reasonably right (“I'm also a version freak, an alternate freak; I need options, a range of choices. Everybody kept saying, ‘You've gotta lock the film.’ But I wouldn’t lock the film until I locked the film. It’s a living process. Each stage is connected to each other stage”), and, above all, gaining control to make sure things stay right.

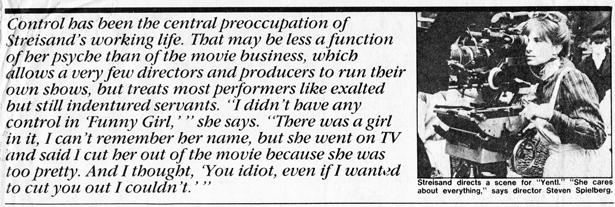

Control has been the central preoccupation of her working life. That may be less a function of her psyche than of the movie business, which allows a very few directors and producers to run their own shows, but treats most performers like exalted but still indentured servants.

“I didn't have any control in ‘Funny Girl.’ There was a girl in it, I can't remember her name, but she went on TV and said I cut her out of the movie because she was too pretty. And I thought, ‘You idiot, even if I wanted to cut you out I couldn’t.’ ”

She had problems of a different sort on “The Way We Were.” Her director, Sydney Pollack, was a man of great modesty and even greater accomplishments, and she thought the world of him. “He’d been an actor himself,” she said, “and he’s very sensitive to other actors.” The feeling was mutual. “My recollection,” Pollack said recently, “is that it was an absolutely perfect collaboration. I could not have wanted in any of my dreams or fantasies anyone more talented or cooperative. As a matter of fact, when I used to read stories about her being difficult, I’d think that must be somebody else they're talking about, it’s not the person I worked with.”

Nonetheless, he was still the director, and she was still the actor. “I could tell Sydney and Maggie (Booth, the editor), ‘Please don't have me crying here, save it for two moments and not four or five.’ But the choice of the director was different, and that's hard, especially when you're the kind of actor I am who believes in serving the director’s vision to the best of your ability. I said to myself, ‘I can’t stand this feeling. I don’t want to be crying here, and I have no control.’ ”

“I want to be in these films where you play an important scene in long shot, or the camera stays on your back or something a little less explicit than you'd expect. And yet sometimes it ’s better to be old-fashioned, to put the camera in the predictable position and show it straightforward. So I go from that to I'm not sure what...”

Sometimes the child has been more intuitive than opinionated. The first time I met Barbra was at Columbia Records in New York in 1962, when she was 19. She was doing a 25th anniversary record of “Pins and Needles,” the old International Ladies Garment Workers Union revue from the 1930s. Harold Rome, who'd written the music for the show and was supervising the new record, spoke of her with unconcealed awe. “She's 19 years old, for heaven’s sake. She's not a history student, she doesn’t know a thing about the period, and yet she gets into the songs as if she’d been born to them. I don’t know where it’s all coming from.”

Barbra hasn't always known where it's coming from either. But she has always known where she wants it to go.

“In ‘I Can Get It For You Wholesale,’ when I was also 19, I came into an audition for the Miss Marmelstein number and said, ‘I would like to do this sitting down for two reasons: one, because I'm nervous, and two, because, since I'm a secretary, I thought it would be logical to do it sitting on a rolling secretarial chair.’”

Her 1962 portrayal of Miss Marmelstein — Yetta Tessye Marmelstein, the plaintively kvetchy and more than slightly lascivious secretary who never gets called by her first name, was the sensation of that season. And her choice of doing the number while sitting on a beat-up old wood-and-Naugahyde secretarial chair was the perfect choice: Rolling chairs are what poor put-upon secretaries get confined to every day of their working lives. But 19-year-olds with smallish parts in Broadway musicals aren’t supposed to make choices, they‘re supposed to follow orders.

“I spent weeks trying to convince them to let me use my chair. I was told ‘You‘ve got no discipline, you can’t do anything twice the same way,’ but I kept asking for my chair, and they started thinking ‘Oh, my God, we‘ve got a kid with some kind of chair fetish on our hands.” Finally they said, ‘All right, use your chair if you want to,’ and when we opened in Philadelphia I stopped the show. I can’t tell you how I felt stopping that show. I felt guilty is how I felt.”

“I’m doing these films where everything is so pat, but every day I learn something, every day I discard something, every day my ideas change slightly ...”

She loved working with William Wyler on “Funny Girl.” His style was old-fashioned by her lights, and he was deaf in one ear, but he had a distinguished directorial career behind him and he never turned the deaf ear to her questions or suggestions. “On the first day of shooting, where I was coming out as a Ziegfeld girl from the train, I said: ‘This could be a great takeoff on the Garbo thing where she appears in a cloud of smoke.’ He shook his head and said no. OK, so it was no. But the great thing about Willie was you could always talk to him and get a straight answer.”

When she first talked to Gene Kelly, her director on “Hello, Dolly!” she asked about his concept for the film, how he saw it cinematically. “He didn‘t have any answer at all. I couldn’t understand it, because there were so many possibilities. I thought it could have been a wild film.”

This compulsive need to involve herself, this slow dissolve from a not-exactly-passive Dr. Jekyll to an all-inquiring Mrs. Hyde, did not endear her to everyone she came in contact with. Her co-star on “Dolly,” Walter Matthau, was a passionate unadmirer.

“One day I had an idea about something I thought would be funny involving a scene in a wagon. I said, ‘What do you think of this?’ and people started to laugh. But all of a sudden Walter Matthau closed his eyes and started screaming: ‘Who does she think she is‘? I’ve been in 30 movies and this is only her second, the first one hasn't even come out yet, and she thinks she's directing? Who the hell does she think she is?’ I couldn't believe it. I had no defense. I stood there and I was so humiliated I started to cry, and then l ran away. And what came out in the papers was Walter Matthau complaining about Barbra Streisand.”

(A personal note here: Matthau’s hostility toward Barbra predated “Dolly” by several years. In 1965, when my ex-wife Piper Laurie was opening in a revival of “The Glass Menagerie” and Barbra came backstage to see her, Matthau poked his head in the dressing room, took one look at Barbra and said: “Oh, you must be Barbara Harris. You ought to get that nose fixed.”)

“After three pictures I still don't know the names of the lights or the lenses. I guess if I was really going to try to direct I would learn the difference between the 50 and the 75 and what it does to backgrounds and so forth. I’m lazy, though. I'm really not interested in knowing it ...”

We were together for the end of the world. It was in New York in 1966, the day the lights went out. Barbra, my wife and I were in our 10th-floor apartment, staring out in bewilderment at the blacked out city. Barbra's husband, Elliott Gould, was somewhere out there in the darkness, trying to get home. Suddenly the news came over the transistor radio that the lights were also going out in Providence, Boston and Montreal. Who knew about power grids half the size of a continent then? We thought it was sabotage, and that a nuclear attack was imminent.

Two or three minutes later the radio said that it was indeed a problem with the power grid, and gave us to believe that life would go on. I remember how quickly Barbra threw off the terror that had gripped the three of us for a brief eternity. Practical soul that she was and still is, she seemed pleased that the world hadn’t ended, so she could get on with her phone calls and appointments.

The trouble was, for Barbra as well as the rest of us, that it was the same old world, with the same old problems. She’d gotten rich and famous in the four phenomenal years since “l Can Get It For You Wholesale.” She'd demanded and received complete artistic control over her first TV special, which was a remarkable production in its own right. Yet every time she signed on for a new feature film, she found herself back in the role of a precocious child trying to please directorial daddys of widely varying talent and wisdom.

When the director was someone she respected, like Sydney Pollack or Irvin Kershner, who directed her in “Up the Sandbox,” she could relax, enjoy, Iisten, ask questions and save string for the future. As her professional power grew and she began producing her own movies, however, Barbra’s career took a new and dangerous turn. On movies like “The Main Event” and “A Star Is Born,” she had final cut as producer, so her working relationships with the directors were doomed to be difficult from the start. She was a producing star who was yearning to direct, and they, by the very nature of their contracts, were now the indentured servants.

Barbra talks about this period of her life in different terms. “In order to gain more control at the end, and even though I was petrified to do, I picked directors who would collaborate with me, people I could have input with.” But she acknowledges that her strategy was a mistake. “I realized I couldn't have a middleman any more. I either wanted to work with very strong directors I could trust, or direct a movie myself. I knew I was taking the chicken way out.”

She still had years to go before making “Yentl,” years of taking meetings and talking terms and negotiating earnestly as a would-be director with studios she’d make hundreds of millions of dollars for as a star. And years of collecting whole balls of string.

“l never saw anybody plan and work like that in my life,” Sydney Pollack said. “l mean, for five years before production she was talking to everyone she could about it. I’d go to a party and she'd come over and say, ‘Now look, if I want to begin on the rooster on the weathervane on top of the church, how would I ....” She was consumed. But it paid off. She went in there as a first-time director and knew exactly what she wanted.”

“I met this new director from Czechoslovakia. His name is Milos Formam, and he’s just made a movie called, ‘Loves of a Blonde.’ I’d like to make pictures like that. I don’t want to make any more pictures with the backgrounds always in focus ... ”

Steven Spielberg, a friend of Barbra's who is no stranger himself to spectacular feature film debuts, is so enthusiastic about her work in “Yentl” that he’s been saying she could have one of the most exciting directorial careers since Francis Coppola. Spielberg was struck by the generosity of her direction. “I think she tried to put everyone ahead of her in her list of priorities. lt’s selfless directing. There was no ego involved at all.” He also expressed amazement at her eye for detail. “l think it comes from the fact that she just cares about everything, from the smallest bit of behavior to the dubbing to the mixing of her sound tracks and the correction of her color.

“l have a feeling,” Spielberg said. “that all this comes from her experience not as an actress being directed and watching other directors work, but from her autonomy as a musician and a vocalist. She's had final cut over her songs since she was a little girl. If you listen to her songs, they're impeccable on every level. That‘s really Barbra directing herself.”

As a tangible measure of her personal as well as her professional growth, Barbra was finally able to use both sides of her face fully. She‘d favored the left side throughout her working life, rarely using the right side in closeups. But “Yentl” changed all that. “lt felt wonderful,” she said, “because (A) it was meant to be — it was so right for this piece, l'd always felt I looked prettier on my left side and more masculine on my right side, so my right side was perfect for playing the boy — and (B) I had no time as a director to wait for the actress to figure out how she would look better.”

“Yentl” is about growth, and how nothing is impossible if you‘re willing to take risks. “Nothing‘s Impossible” is the catchphrase of the ads, but it’s also an article of Barbra's faith, as well it should be. Milos Forman made it to America, and Barbra made it to Czechoslovakia, where she shot the exteriors for “Yentl” two summers ago.

She went there as a mature woman of great wealth and attainment, yet she directed the picture like an audacious, impassioned kid — as if her life depended on it. She didn’t take the chicken way out, except for some scenes with chickens, and with her eagle eye for detail, she made sure lots of backgrounds were out of focus.