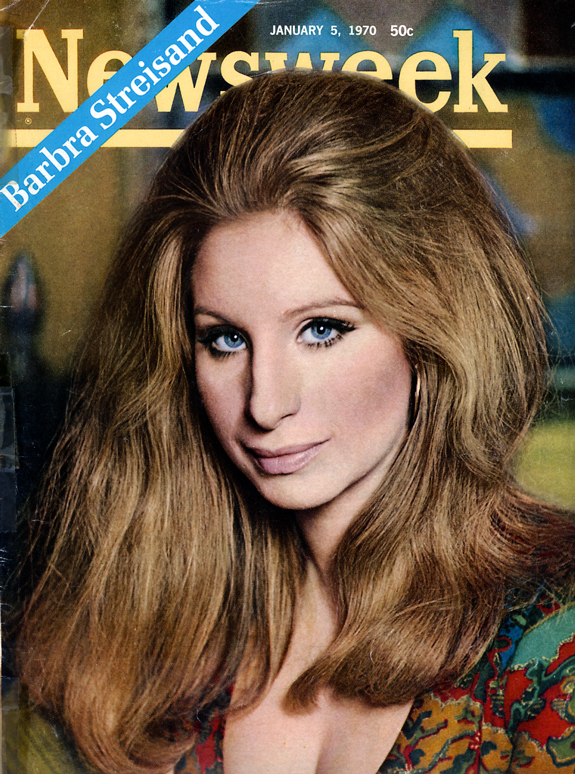

Newsweek

January 5, 1970

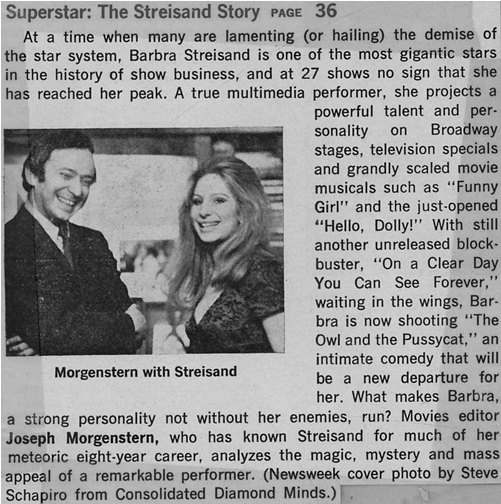

SUPERSTAR: THE STREISAND STORY

by JOSEPH MORGENSTERN

By any standard but raw musculature, Barbra Streisand is the most powerful entertainer in America today. She could get financing if she wanted her next movie to be based on Van Nostrand's Scientific Encyclopedia. (Not such a bad idea: we open on "Photosynthesis," with Barbra in the greenhouse dressed in silver lame gardening togs . . .) She's seen on the screen in "Hello, Dolly!" in 70-mm, Todd-AO, she's heard on records in 360 Stereo Sound and she's dissected by gossip columnists in 8-point malice. The movie version of "Funny Girl," her first star vehicle, which won her an Academy Award, is still playing on Times Square. "On a Clear Day You Can See Forever" will be released next spring, and she's now shooting "The Owl and the Pussycat" in New York.

Several of her TV specials have been stunning. Her records have sold nearly 9 million copies. She seems to be seen everywhere, and the volume of copy is vast about what she does, where she goes and with whom. How she wields her personal power is one thing. How she uses her artistic power is another, though, and it is the essential thing about her, as it has been ever since she appeared on Broadway more than seven years ago as Miss Marmelstein in "I Can Get It for You Wholesale." What matters most about her is her gifts, or her art, or whatever you want to call it. It's how she's able to make such a lot go such a long way.

She made her Miss Marmelstein entrance in a swivel chair: Yetta Tessye Marmelstein, a bizarre, beehived, unbeloved child of 19, swooping and swiveling toward us to ask why other girls get called by their first names right away. "Oh, why is it always Miss Marmelstein . . .?" She chose that preposterous chairbound entrance because she was too scared to face her audience standing up and because most secretaries, she figured, spend most of their time in chairs anyway. A great performance is a collection of such precisely right choices: theatrical, extravagant, but above all true. She rolled on stage, and then the most peculiar thing happened. This beehive office girl who really seemed to have come out of an office put on a whole little musical by herself. It was heroic, in its way, and desperately funny.

Wallflower: The heroine that she so quickly became had a particular desperation all her own. She was a wallflower. She had this Jewish problem, and this homely problem. "Nobody Makes a Pass at Me," she sang in the 25th anniversary recording of "Pins and Needles," a garment workers' union show with a charming score by Harold Rome, who also did the "Wholesale" score. It was much the same character that Rome had written in the Miss Marmelstein number, except that Barbra threw new anger into it, comic self-hate and harsh self-appraisal. "Just like Ivory soap, I'm 99 and 44/100ths per cent pure," she wailed, and the "pure" came out as a filthy word. PURE!

She was purely her own invention, nothing prefabricated, no resemblance to starlets living or dead. She was a regular person with a genuine past from a real place that happened to be Brooklyn, which made people laugh. She really was pure, but pure what, exactly? Her first starring role. Fanny Brice in the Broadway production of "Funny Girl," supplied one answer—pure oddball. It was such a persuasive answer that it seemed for a time to be the only one.

"When you're younger," she said slowly and cautiously in a long discussion of her work one recent evening, "you have only your imagination to draw on, so what happens is it transcends reality, it almost makes its own art." She was talking, at this point, about her work as an acting-school student of 16 or 17. (According to a friend who knew her then, she was the only one in the class who asked questions, who wasn't passive, wasn't awed by the teacher or the material.) "As you get older," Barbra said, "reality sets in."

Whatever its shortcomings as a cohesive piece of theater, "Funny Girl" made remarkably shrewd use of its star. The choreography gave her a chance to do some sublime clowning in the "Beautiful Bride" number, in which Fanny, surrounded by long-stemmed beauties, sang sweetly that she was the beautiful reflection of her love's affection, which was all well and good except that the girl was visibly, hugely pregnant. Isobel Lennart's book gave her an antic facade and a romantic, passionate spirit. The score, by Jule Styne and Bob Merrill, gave her two distinctive ballads—"People" and "The Music That Makes Me Dance." Most shrewdly of all, the score provided an opening number, sung not by Fanny but by her friends and neighbors, that briskly explored the problem of success, sex and the homely girl: "If a Girl Isn't Pretty" ("If a girl's incidentals aren't bigger than two lentils ...").

In her own opening number she sang wistfully, comically, that she was the greatest star but no one knew it. By the time the movie version of "Funny Girl" came out in 1968 almost everyone knew it. Rather, they knew with more than a little skepticism that she was supposed to be the greatest. But Barbra had never made a movie, and cameras are notorious unmaskers of fraud. The cameras in "Funny Girl" unmasked an artist even more gifted than she was supposed to be. I remember worrying about superlatives in my review. Would I make a fool of myself by calling it the most accomplished, original and enjoyable musical comedy performance ever put on film? I searched my memory and finally decided that, what the hell, it simply was the greatest; why not say so?

Livepan: But what do such superlatives mean? What did she do that was so good? A fair question to ask and a hard one to answer, since the one thing she didn't do was hold still long enough for the categorizers to draw a clear bead on her. She did a livepan deadpan, a deadpan livepan. She had her ethnic material at least both ways, comedy and parody plus a bit of self-parody thrown in whenever she wanted to play dummy to her own ventriloquist. She worked a warm, roman- tic singing voice against a taut, comic speaking voice. Her transitions from one mood to the next were instantaneous and dazzling. In the scene leading to "Don't Rain on My Parade," she put her hands over her ears, shook her head and said "Don't tell me" as her fellow Follies girls tried to convince her that her man, Nicky Arnstein, was a stinker. Suddenly, without warning, she was into her song, repeating "Don't tell me" with an explosive "Don't" that carried her all the way to a tugboat deck and intermission.

Her energy was limitless, her sense of fun almost infallible. And at the end of a movie that didn't have its own dramatic end-poor pasteboard Nicky comes back to Fanny from the hoosegow but their marriage has nowhere to go—Barbra sang "My Man." She had the sound recorded live, an artistic gamble which most movie stars wouldn't dream of taking. She wore black against a black background: nothing to be seen or heard of her but two hands, a face and a voice. She started small, injured, all trembly-tearful as if there were nothing else to do with an old chestnut about a lovelorn lady. Before the end of the first chorus, however, her funny girl made a decision to sing herself back to life. Her voice soared defiantly, a spirit lost and found in the space of a few bars, and since you'd paid your money you could now take your choice of being wiped out by the sheer, shameless sentiment of the situation, or by the virtuosity of an actress looking lovely, feminine and vulnerable at the same time she was belting out a ballad with the force of a mighty Wurlitzer.

We talked about typecasting. Italian audiences had no interest in seeing Marcello Mastroianni's superb performance in "The Organizer." They wanted their romantic leading man, not a union organizer out of the smoky past. American audiences were indifferent to Gary Grant's fine work in Clifford Odets's film about an ill-starred Cockney, "None but the Lonely Heart." "I suppose the audience just didn't buy it because they want what they understand," Barbra said uncertainly, with no pleasure at the thought. "But ... I can't buy that either. I always think if something's really good and right they've got to buy that. I mean I want to play all different kinds of parts: you know, from bitches to sweet girls to stupid girls to bright girls to every kind of girl. 'Cause I have all these possibilities. I'm slightly dumb, I'm very smart. I'm many things. You know? I want to use them, want to express them. It's kind of funny, because I'm in these sort of big pictures and yet I'm an odd ... I'm an odd ball. I mean, I'm not a Doris Day or a Julie Andrews. That's what's weird about it. I don't know how I got into these things. Honestly."

She mistrusts the press but trusts the audience. "The audience is the best judge of anything. They cannot be lied to. I mean, this is something I discovered . . . not discovered . .. but after almost two years on the stage one learns that. The slightest tinge of falseness, they go back from you, they retreat. The truth brings them closer. A moment that lags, I mean, they're gonna cough. A moment that is held, they're not gonna cough. They don't know why, they can't intellectualize it, but they know it's right or wrong. Individually they may be a bunch of asses but together as a whole they are the .. . wisest thing."

Of all the gossip that's gossiped about her, the most intriguing part is her reputation for being difficult to work with. She has this habit, people say, of directing her directors. People often say that about stars. Power is a fascinating subject, and people love to think of moviemaking in terms of power and nothing but power, as an epic struggle between ego-maniacs: on one side the director, wearing jodhpurs, boots, riding crop, monocle and leer; on the other side the star, fussing with her face and refusing to play her scene in the county workhouse unless they let her wear the Golden Fleece. One never knows the truth of these things. The actor- director relationship is uniquely intimate. One can only make guesses based on the movie's end result.

Her director in "Funny Girl" was William Wyler, a man of vast experience and proven artistry. He'd made some 40 movies before this; Barbra had made none. She, on the other hand, had created her own role, had played it 798 times on Broadway and in London and knew more about it, instinctively and intellectually, than anyone else on earth. There was every reason for these two artists with complementary equipment to collaborate on the film and—based on the strong end result—every reason to believe they did collaborate. Not without anger or pain, surely, since stars and directors are both playing for high stakes in such elaborate productions, but not without purpose either.

As a matter of fact, if Barbra directed Gene Kelly, her director in "Hello, Dolly!", she should have done a better job. There's no evidence that he or anyone else directed this great, plodding dinosaur of a film. It's there because it's there, an impressive industrial enterprise in which everyone came dutifully to work in the mornings and picked up where they'd left off the day before. Kelly stages his turn-of-the- century comedy in late 1940s style, as if movie musicals stopped growing when he stopped dancing in them. Like Michael Kidd's choreography, Kelly's technique is antique at best, incompetent at worst. Several shakily written comedy scenes are just as shakily performed because no one knew how to direct or cut them. The "Hello, Dolly!" number comes in fits and starts because no one knew how to make it build, visually or dramatically. The 40 million extras in the big parade scene look like a routine rabble because no one knew where to put the cameras.

Fight: Like her co-stars-Walter Matthau as Horace, Michael Crawford as Cornelius-Barbra has an uphill fight with the foolish material and the flatfooted style. She needs help and doesn't get it, and it hurts. In search of a center for the character of Dolly Levi, she finds two, three or four centers and therefore none: Mae West, Vivien Leigh, Fanny Brice, even Barbra Streisand. She's too young for the part of this doughty Mrs. Fixit, so she does some of her best work out of character. Yet the movie dies utterly when she's off screen and comes obediently back to life when she's on. She may be in trouble from time to time but she bails herself out, and the movie as well, with great resourcefulness.

She spoofs the dumb material, or goes with it, or plays with and against it almost simultaneously. "Such a long life line!" she cries in mock amazement as she reads Matthau's palm, then continues to read it like a hip gypsy. Leaving Matthau in the second act, she does another lightning transition from speech to song—"So Long Dearie" —with seven preposterously impassioned good-bys that she sings, trills, yodels and groans in the styles of Piaf, Marlene Dietrich and, for all I know, Lucrezia Borgia. Trapped by a scene in which Dolly teaches the waltz to an actor we know perfectly well is a professional dancer, she shows him the first rudimentary one-two-three, stands back while he does some exuberant look-ma-I'm- dancing adagios, and then cuts through the whole choice idiocy with a muttered ad lib: "I think he's been holdin' out on us."

As in "Funny Girl," she does a parade number, "Before the Parade Passes By," for her first-act curtain. She's alone on the screen at first, a warm, throbbing body in coarse cartoon-land. Her Dolly is trying to gather her forces in this first chorus (force gathering is what first-act curtains are all about) so she can make her way back into the parade of life. Then there's a drum, and then an elephantine production number that takes the metaphor of the song literally: a parade with 76,000 trombones and the entire membership of the Screen Extras' Guild. And the most amazing thing of all is that the parade itself, for all its blare and vulgar trappings, never comes up to the power of Barbra's performance in the first chorus, just as the whole "Hello, Dolly!" production number adds very little to the outlandish delight of her entrance, a middle-aged marriage broker being played by a sexy young woman in a sparkling gold gown. The girl is human, the production ain't. Who needs it?

That's an odd thing for an oddball to be taxed with, looking sexy and young. Was it done with mirrors, or with Irene Scharaff's costumes, or with Harry Stradling's photography? No, the suspicion doesn't withstand scrutiny because the girl does withstand it. She looks lovely on screen and off, so much so that you wonder what happened to her and when. Had she been taking ugly pills for the "Funny Girl" role and then quit cold turkey? The answer, of course, is that her publicity and her material in the first few years of her career told us she was an oddball, so an oddball is what we saw. She looked lovely in all but the most antic comedy routines of "Funny Girl," yet the material kept saying Homely, Clumsy, Gawky, Screwy, so we took our cues. On records she was singing "Lover, Come Back to Me" with superbly dirty sexuality five years before "Funny Girl" hit the screen, and singing her slow, sensual versions of "Happy Days Are Here Again" and "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" six months before that. The main and basic source of the confusion was that she'd started her Broadway career as a little old maid. Only later did she youthen.

What kind of actress is she? Where do her strengths lie? "Elliott [husband Elliott Gould] once took his great-grand- mother to see me and she was about 85, and she said she liked me because I was so natural-so natchel. And I liked that. I guess my best attribute is my instinct. It just... it hurts me if I hear a wrong line reading or something. And there is no such thing as a wrong line reading, only there is. I mean, everything is so damned . . . needs to be qualified so." A line reading that didn't work, then? "Yeah. Right. It's like music. I mean, acting is even like music. Because I believe in rhythm, you know? Everything is so dominated by our heartbeats, by our pulses, when one goes against certain rhythms it's jarring, it's unnatural, unless we use the dissonance."

She was squirming now and embarrassed by herself. "I'm not articulate and I'm not eloquent. This makes it sound like a lot of crap. It just sounds awful I mean I hear it! But the point is I read a script and I just hear and I see what the people are doing, and I'll have an idea right off the bat, and it's always my first instinct that I trust. I'm also very lazy so I don't delve much further."

When her first flop comes, what kind does she want it to be? "A big one," she grinned. "So I can have a good comeback."

What about other styles of acting? She didn't feel close to actors with "thought-out line readings—you know, they know exactly where the intonation goes, what the key word in the sentence is, what they're reaching for in their speech or whatever. I'm more moved when I see Brando, when I can't quite define his moments, when I see just a life, a mind, a personality. Brando is stronger than any of the characters he plays. There is a difference between preconceiving everything and having it in control, and when it's slightly out of control."

Mercurial: We talked about specific performances, agreeing on Jeanne Moreau's mercurial work in "Jules and Jim," different from one second to the next and yet a perfect whole. She expanded on it enthusiastically. "Anything carries when you have conviction. You can be totally different or have the moods change or switch from serious to comedy if you believe it, and everybody will go along. One little shred of doubt, though, and you've lost them all, you know? You have to just do it. It's wild, you know? I mean, the strength of the will, the strength of conviction. I don't know, what is conviction? Is it red or blue? It's so intangible. What . . . what chemical transmits itself in doubt? One flicker of doubt and everybody—gets doubtful. And most people are followers. They need you to be sure. They might resent you for being sure but they need you to be sure. They would fall apart if you weren't sure."

She isn't altogether as free as she'd like to be yet in her performances; the rehearsals are still sometimes better than the takes. She still worries about the way she looks, and worries about worrying about it. Every actor, man or woman, is a narcissist by trade. The trick is to accept this concern with one's body and put it in the proper place—concern and body both. She thinks of herself primarily as an instinctive actress, and her instincts are indeed phenomenal. Yet she can also get hung up temporarily on irrelevant details-a question of gum chewing or something, or the arcane symbolism of some costume. And this confusion is compounded by the fact that irrelevant details may also be crucial in their way. Barbra has an extraordinary grasp of how costumes can define character, and an actress who's worried about gum- chewing techniques in a particular moment may actually be freeing herself to do the important work in the scene with- out thinking about it.

Her completed movie work to date consists of three elaborate musicals: "Funny Girl," "Hello, Dolly!" and "On a Clear Day You Can See Forever," which was directed by Vincente Minnelli. Barbra and musicals have done well by each other. But she's ambivalent about her singing now. She seems to be suggesting that she doesn't want to do any more musicals-no more pat, flat spectacles, the kind with the backgrounds in focus. She knows there are less rigid, less predictable ways of making movies these days, and she'd like to join in the fun. But First Artists, the new movie company she formed six months ago with Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier, has not yet announced a single production, and her own methods for searching out new material are haphazard.

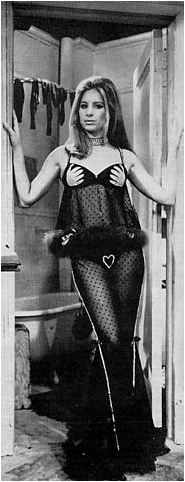

In the meantime, however, she's gainfully and happily employed on "The Owl and the Pussycat." She plays a hooker, Doris ("I'm an actress and a model ..."), to George Segal's Felix, a pseudo-intellectual, in this movie version of Bill Manhoff's Broadway play. Neither Barbra, director Herbert Ross nor anyone else connected with it would represent "The Owl and the Pussycat" as a piece of avant-garde filmmaking. It's a romantic comedy, and it's intended to make people laugh. But it does represent a significant step in her career. It's an intentionally small-scale movie being shot under extremely low pressure at several New York City locations and mainly in a dinky studio on Manhattan's West Side. Its characters and dialogue have some basis in reality, if not necessarily in natchelism. It's not a musical, though she hums a bit. She has some near-nude scenes in it and the movie, to her great pride and pleasure, is X-rated.

(Photo, right:) With 3-year-old Jason: Just a regular person

'Lazy': She even enjoys the unnude scenes. She's at ease with herself on this film. She says she's getting increasingly lazy in her work, but what that means is that she's getting decreasingly compulsive about details that don't matter. Notoriously late in the past, she's a model of promptness on the job. She respects her director and leading man and takes pleasure in a well-founded belief that the feelings are mutual. She likes working in New York, where the men on the crew talk like she does and she can go home after work to her apartment and her 3-year-old son Jason. Up in Central Park for location shooting one recent afternoon, she looked too pretty to not touch in a brown and white Dynel imitation lynx coat and white boots. She and Segal were shooting a scene in which he throws her to the ground and humiliates her until she cries. The scene was difficult for several reasons. It was freezing cold. A pot of charcoal embers hung under the Panavision camera to keep it warm, but there wasn't any charcoal for the actors.- They had to make their wrestling look spontaneous and free while at the same time hitting their marks to be in focus. Finally, Barbra had to cry at the moment that the camera moved in for her close-up.

Even the lowest-pressure production can put the squeeze on an actor. The afternoon sunlight was failing and here they were with nary a wet eye in the house. Cry and the world smiles with you. But she couldn't cry, and she couldn't forget that she was supposed to appear a few hours later at the premiere of "Hello, Dolly!" at the Rivoli Theater on Broadway. She racked her brain for a way to make herself cry. The device she claims to have found was the thought of how guilty she'd feel if she went to the premiere of another movie and hadn't done her work properly on this one. It may not be so, but it makes a good story. The fact is that the camera turned, the tears flowed, the shot was made and the girl went home. Smiling.

Willing: "I can't tell you how marvelous she's been," said Ross, a tall, soft-spoken man who has known her since he did the musical staging in "I Can Get It for You Wholesale." "It all comes out sounding like platitudes, but she's so generous —willing to do it my way or George's way. She has a feeling not that everyone loves her but that she's one of us." He spoke of one scene with Segal and Barbra in bed "where she takes off her bra, and it wasn't easy for her at first. She had so many inhibitions to throw off. You know, 'What would my mother think of this?' Once she did it the first time it was easy for her, but it really cost her."

Ross had directed Peter O'Toole in "Goodbye, Mr. Chips," and he said O'Toole and Barbra were the two best actors he's ever worked with. "She isn't technical the way Peter is, a highly disciplined, highly trained actor. She has this ability to make right choices intuitively. But they're both alike in a way. They're never unprepared. They always know who they are and what they're doing. There may be areas within a scene that she's a little fuzzy about, and sometimes she'll get hung up on a little thing, a trifle, but the essentials are always clear." Before doing this movie, he said, he wouldn't have known what to think about her future. "But now I think her range is incredible. She's really what acting is all about—being. The more she tests her range the more expanded that range is going to be."

The most frightening part of stardom, superstardom or whatever the position is that Barbra occupies at this point in her professional life is that it inhibits growth. The historical pattern is plain. A star succeeds, repeats the success, varies the repetition slightly but insignificantly and ends up in a prison of self-parody. The most promising part of Barbra's case is that the pattern may not apply. She seems genuinely eager to test and expand her range, to grow in many directions. If she's only now beginning to be free as an actress, then the best is yet to come.

There would seem to be an undeniable logic to what she's doing now, getting out of those lavish musicals while the getting is good. The studios are collapsing and the studio chiefs, in self-preservational frenzy, are blaming it all on big-budget productions. The true culprits, however, have been bad big-budget productions. "Funny Girl" has made a fortune for its producers, despite its initial cost. Thanks to her presence, even "Hello, Dolly!" has a chance of making back its $25 million cost, though the logic of that budget is, of course, indefensible. To judge from the production photos, "On a Clear Day You Can See Forever" has invested a queen's ransom in costumes, as well as salaries, but there's no reason to think the ransom won't be recouped.

Hopefully, Barbra will do plenty of small movies that leave her free to explore character, reality, the finer texture of life. Hopefully, too, though, she'll be able to think big and sing big and work big again if she wants to. It was great fun seeing her on that tugboat with the Statue of Liberty in the back- ground—in focus. It should be greater fun to watch her pump new life into the musical-comedy form and find new ways to use music in movies; any movies. When a girl can sing "Any Place I Hang My Hat Is Home" the way she does, her voice ought to be free to pop out of its cage at will.

Outtakes

(Bonus photo, below: An alternate shot, not published in this edition of Newsweek, taken by Lawrence Schiller)

Below are the outtakes from Steve Schapiro's sitting with Streisand—his photograph of Streisand was utilized on Newsweek's cover. One shot was used to advertise her engagement at the Riviera Hotel ...

Steve Schapiro recalled photographing Streisand for the session: “Newsweek came to me to shoot it, and we shot it in her apartment. [...] Barbra had decided on the wardrobe. I hadn't done a lot of Newsweek covers at that point. I'm coming with somewhat ridiculous equipment in the sense that I'm going to shoot at a camera aperture of f-2.8, which gives you almost no depth of field. I am holding a small strobe unit in my left hand — assuming that I'm going to be able to bounce light off the ceiling and keep everything in focus—and doing everything else with my right hand [...] We shot five or six rolls of 35-millimeter. Luckily it turned out to be a great cover.”

END