She Is Tough, She Is Earthy, She Is Kicky

July 4, 1965

by Martha Weinman Lear

In the far, moon-dappled reaches of Biloxi, Miss.—and there is no further reach from the milieu that produced Miss Barbra Streisand (born Brooklyn, 1942; graduated Erasmus High School; worked as switchboard operator; won singing contest; met David Merrick, and so, and so, and so)—three students from Gulfport High School stood about of a recent evening and pondered a dream incarnate.

“Oh, mah, she is tough,” said Robin Adams, 17. “She is earthy, she is real, she is ethnic.”

“Ah jes love the way she looks,” said Linda Miller, 16. “Ah tried to wear mah hair like hers, but it jes wouldn't go like that. Ah wish Ah could talk the way she does. She talks diffren.”

“She is kicky, thass all,” said Craig Stevens, 17. “No, not kooky. Kicky. Like free. Un-in-hib-i-ted. She does what she wants, and she has an image of her own, y'know? Sort of a female James Bond. We all love somebody with a diffren image.”

Biloxi, man.

(Photo, right): Like any emphatic, high-voltage personality—Ethel Merman, Charles de Gaulle come to mind—Barbra Streisand inspires a dedicated anticult as well as cult. To some (like these autograph seekers, above), she has “duende.” To others, she is “too damn delicatessen.”

Mr. and Mrs. Elliot Gould—both of the theater, she being Miss Streisand—own a 1961 Bentley, beige. They used to own a Rolls-Royce, and a chauffeur. But the Rolls stalled the very first day they bought it. The chauffeur, it was learned, washed his socks in the kitchen sink and used their bathtub when they were out. And one evening, when they were entertaining guests on the terrace, the chauffeur, doubling as houseman, came out to serve blueberry pie, and even in the softly fading twilight it was impossible to miss the blueberry—lone, plump, condemnatory—that hung suspended at the corner of his mouth. The next day the Goulds got rid of the chauffeur and, severing all unhappy ties, the Rolls as well, and bought their Bentley.

Now, Mr. Gould does not let his wife drive the Bentley, or so she says. Like any emphatic, high-voltage personality—Ethel Merman, David Susskind, Charles de Gaulle come to mind—Miss Streisand inspires a dedicated anti-cult as well as cult. Its numbers are limited, but they make a lot of noise. And one of them, himself a 150-watt personality, has been so uncharitable as to suggest that when Miss Streisand wants to drive the Bentley, she doesn't say please. She says, “Push over, People, I'm driving.” This conjecture is probably false, and it is probably true, as most conjectures about Miss Streisand are.

At any rate, what waited at the curb of her Central Park West apartment building the other day was not the Bentley but a station wagon. In it was a close friend who has come, as close friends of famous people so often do, to cherish anonymity—her name is Sis—and Miss Streisand's decorator, Charles F. Murray. [Barbra-Archives note: this is probably Barbra's friend, Cis Corman] Miss Streisand, dressed in black visor cap, black pants, black boots and black blouse relieved by a sprightly stripe of beige, descended from her nine-room duplex and strode to the car. People watched. Pretty? Heavens no; but striking, a sow's ear transformed, by instinct, hard work and sheer will into a sleek silk purse of a face, an original.

“Hey, Sis,” she said, “can I drive?” Sis slid over, and Miss Streisand started up with gusto. The party was bound for a thrift shop where, Mr. Murray informed his client, there awaited a splendid lot of antique porcelain. “She's really terrific,” he said, sotto voce. “We've been working on her apartment for a year, and the knowledge she's picked up is fantastic. Also, she has an innate feeling. She knows when something is right or wrong. Some day she will be a great lady with great collections.”

A cabbie swung close and bellowed out happily. “Hiya, Barbra. Hiya, Barbra baby.” Miss Streisand grinned back, addressing several snappy salutes to her visor. “Yeah, yeah, sure,” she said. “Hiya, baby.” At a light a couple moved in quickly, requesting her autograph for their daughter. “Whaddya mean, daughter?” said Miss Streisand, signing. “Why not for you?” She slowed down respectfully as she passed a Good Humor truck. “Oh, Sis,” she murmured throatily, “banana splits, huh?”

“And there's this little-girl quality,” Mr. Murray said. “She's beguiling ...”

The thrift-shop proprietress, a tulip-shaped lady named Ida, was clearly beguiled. She burst into full bloom at Miss Streisand's entrance. “Barbra, you look stunning,” she said. “Have I got something for you!”

Miss Streisand picked up a plate, scrutinized it, fondled it. “French, 18th century,” she said. “This is one of the two cornflower patterns made for Marie Antoinette. Beautiful, Ida, beau—oh, God!” Her gaze had moved to Ida's person and now clung there, awe-struck, the eye of Keats encountering Truth. “Ida ... where did you get that suit?” Wholesale, Ida said. “I've got the same suit! And you got a matching blouse! And I didn't! Where did you get the blouse, Ida?” Ah, said Ida; she'd had it made and, what's more, she just might have enough fabric remaining for Barbra. A wonderment. “For two years I've been hunting for a matching fabric,” said Miss Streisand, “and I come walking in here ... Oh, fun-ny. That's fun-ny.”

She spied a small silver ash tray engraved with a "B." “That's lucky, Barbra,” Murray said. “I know,” she said. “But listen, Charles. Fifteen dollars. I bet you could get it in Tiffany's for that.” Still, it was too lucky to resist. She paid, protestingly, the $1 for the ash tray and, unprotestingly, some $600 for the porcelain, and adjourned for lunch at a White Tower across the street. (“It's not put on, she loves White Towers,” says choreographer-director Joe Layton, who supervised her recent television special, My Name is Barbra. “She knows all the funny little places. She's always taking us into dark little Second Avenue doorways where you can get lemon sherbert at 3 in the morning.”)

Miss Streisand munched a second hamburger. “You're a great cook, y'know?” she told the counterman. One coffee, she said, to go; she had promised to take it back to Ida. Ida bloomed again, and an elderly gentleman—her husband, perhaps—who had been sitting in a corner, silent as a salable item, smiled benignly. “That's nice,” he said. “Such a big star, she acts so simple, like a plain human being. That's very nice.”

A big star? Miss Streisand rose like a phoenix from the pale embers of I Can Get It For You Wholesale, in 1962, and still fans, almost single-handedly, the tepid fires of Funny Girl. She stands first among female LP recording stars. She holds a ten-year, $5,000,000-minimum contract with CBS. Her television show, wherein she effortlessly—or so it seemed—ran the gamut from nursery rhymes to scorching blues, brought out stratospheric adjectives the reviewers hadn't used in years, and one was moved to call her the Compleat Performer, possibly the best musical comedy star the country has produced. The show is scheduled for a rerun next October—tame stuff for an Astaire, perhaps, or a Martin and Merman, but a hallelujah coup for such a young'un. Yes, indeed, a big star.

But simple? Having reached such eminence, Miss Streisand is now fair game for every lay analyst in the business. There is currently even a certain cachet in putting her down. But nobody—not even the most myopic of the women's magazine philosophers—has seen fit to call her simple.

The thing is, Miss Streisand operates largely from instinct, and her instincts are exceedingly complex. They advance confidently, bare their teeth, stop in doubt, retreat in fear, reconnoiter, burrow sideways, under, over and through. Sometimes they collide; then there is a paradox.

She is known to be shy and to have a chutzpa that is positively baroque; to be Secure and Insecure; Nice and Not So Nice (“Everyone wants to know if she's nice,” an acquaintance said recently. “What does that mean, nice? Who's so nice in this business? Well, OK, maybe Claudia McNeil.”); Artful Contrivance and Noble Primitive—which, to revert fleetingly to an aging parlor game, might also be spelled Intentional and Unintentional Camp—and, of course, she is. How could it be otherwise?

Shy? Uncertain? Her manager, Martin Erlichman, recalls her agitation when she was to be introduced to Frank Sinatra at a party. “What will I say to him?” Miss Streisand moaned. They met and talked and soon she was back at Erlichman's elbow, still agitated. “I think I goofed,” she said. What happened? “Well, he sat me down and went away, and when he came back,” she said, “I stood up.”

On the other hand, her friend Sis (among the few intimates; Miss Streisand is not one for gurgling girlish friendships) remembers Marcello Mastroianni backstage at the Winter Garden, pacing and smoking, pacing and smoking, as he waited to meet Funny Girl's star (“I was nervous just being near him,” Sis says), and Miss Streisand, emerging from her dressing room with no unseemly haste, serene of smile and sure of hand, and welcoming him, after one altogether understandable lapse—“Wow! He's real!”—in Italian. (“She spoke it after 12 lessons. Her piano teacher said she was brilliant after one lesson. She 'gets it' much faster than most people do. That's why she sometimes sounds disjointed. When you're on 'A,' she's already considered 'B' and is occupied with 'C.'”)

Audacious? Jerome Weidman, who co-authored the musical version of his book, I Can Get It For You Wholesale, has recorded with cautious affection the occasion of the cast's first reading. Everyone else paid rapt attention, but Miss Streisand, he noted in Holiday, was totally absorbed in making scribbles on a piece of paper. “When the reading ended, I watched her go up to the press agent. I wandered across and asked what was happening. 'Get a load of this,' the press agent said. 'I asked the cast to give me stuff for the biographical notes. Look what this dame gives me.' I read: 'Not a member of The Actors Studio, Miss Streisand is 19 and this is her first Broadway show. Born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon...'”

In those days, the Streisand Look, a compilation of thrift-shop exotica and face-concealing hair-dos (“That was so she could look out and nobody could look in,” said Mr. Gould, who played the male lead in Wholesale), was what the minor poets called kooky. Now, she wears designer-label exotica and is called High Style, and it is bruited about that she was a very phony kook. “The kookier she was, the more we liked it,” an ex-fan lamented recently. “It was like she was rebelling for all of us. Now it's like, here she comes with all her wigs and jewels, and a lot of us feel betrayed.”

The change, really, is more economic than philosophic. Miss Streisand is innately theatrical, and her appearance has never been designed to lose her in a crowd. But to dismiss it as contrived is simple-minded. Within her, the need to register the rebellious roar has always coexisted with an exquisite understanding of how the roar should be designed, directed and produced.

Miss Streisand considered the matter one recent day, sitting in her apartment. (Living room: period French, pale, Aubusson; study: velvet, paisley, lots of red; master bedroom: Gothic, fur throws, venerable four-poster upon upholstered platform. “Barbra said the next time she decorates she may switch the mood and do a real French whore's bedroom, all chaises longues and satin hangings,” decorator Murray has confided.)

“The way I looked, ” said Miss Streisand, “it was like two things were going on inside me. It was honest, it was the way I wanted to look—a defense, a defiance. But I knew it was right for me, too. Like when I was on PM East [a Channel 5 show on which she appeared frequently in 1961]. When they called me to go on the show, I said to myself, 'What's the big deal? I should go out and buy a dress special for this show? It's not even one of those fancy network shows.' So I'd go like I didn't give a damn, I'd look uglier than I was ...” (“She wore a simple little basic burlap bag,” recalls then-producer Mert Koplin, now president of Off-Network Productions. “She looked like a disreputable Judith Anderson, and she was a completely self-assured, confused little girl”) “... and it was a big, defensive, rebellious thing. But at the same time it was theatrically right for me. I knew it.

“Sometimes I know the right way from watching the wrong way. A guy says, 'That couch should be red'—boom!—I know it should be white. Like, I could never understand a performer getting all involved with his audience. I used to think, 'Listen, don't give me all that. I don't want it. Don't react for me, because then there's nothing left for me to do.' So when I sing, I go inside myself. I'm busy with my own reactions to my own thoughts. Maybe I'm thinking of a big ham with pineapple on it or something, who knows? What does it matter? The point is, I get all involved with myself, and I let them have their won reactions.

“When I was in Wholesale, they yelled at me because I didn't do the song ['Miss Marmelstein,' her show-stopper] with the same gestures every night. I told them, just give me the music and I'll make it work every time. And I did, and then they let me alone.”

Pause. A smile, a sweet moment savored. “There was this stage manager, she kept picking on me. She'd tell me not to chew gum onstage. So I'd provoke her. I'd stick it up in the roof of my mouth and go out there and chew. It bothered me, because ... Listen, what does having gum in your mouth matter if you're doing your job? And even if it did, maybe that character would chew gum. Sometimes gum is right. It's a defiance. Like, I'll always say, 'I'm not gonna do nothing.' And somebody says, 'You mean anything.' And I'll say, 'No, I mean nothing. I'm not gonna do nothing.'”

Such a psyche is no roast beef medium. It is rather more an anchovy, or a steak tartare, and some people just don't acquire the taste. Several hardcore anticultists expressed themselves recently by use of an Andalusian word, “duende,” which means a sort of hobgoblin but has come, in the vernacular, to mean “It,” as in “She Hasn't Got It.” For example, they said, Marilyn Monroe had duende; Jayne Mansfield doesn't. Bogart had duende; Alan Ladd didn't, and Sean Connery doesn't. Callas has it; Tebaldi doesn't. Burton has it; Gielgud doesn't. Garland, yes, they said; Merman, yes. Streisand? Bah.

Curiously, there is no indifference here—Miss Streisand almost never engenders indifference—but a passion of distaste: “A pushcart broad”; “Too damn delicatessen. (But don't get me wrong; I hate that egregious ethnic bit Pat O'Brien does, and I'm Irish Catholic myself)”; and, frequently, a soupçon of malice: “Did you hear the hairdresser joke? A woman came in and asked me for the Barbra Streisand Look, so I hit her in the nose with my hairbrush.”

And across the chasm stand the hordes who haven't cheered so lustily since Judy Garland demolished the Palace. What is noteworthy about the Streisand fans is their diversity; she spans the generations at a time when few performers can span so much as a five-year gap.

When she sang at the Forest Hills Music Festival last summer, the tickets had vanished two days after they went on sale and 15,000 pre-Beatle-ands and post-Lombardoans sat under damp skies, in rare and blissful accord, and shouted for more. (“Come closer, Barbra,” one yelled. “How can I come closer?” she said, regretful but eminently reasonable. “If I walk on the wet grass with the microphone I might electrocute myself.”) She will appear at Forest Hills again on Aug. 8, and nobody doubts that the audience will give the same smash performance it gave last year.

What attracts them all? The voice itself is an awesome thing. “There's no use dissecting it in terms of a cultivated singer,” says The Times's Howard Taubman. “It's big, natural, full of gutsy, brassy sound, and the first time we heard it, this girl really socked us between our eyes. Tutored or not, there was a real personality here.”

The voice can belt out a note with all the gorgeous, growling authority of a Sophie Tucker special, and instantly turn wistful as anything that ever went over the rainbow, pained as the deepest blues in the night. It has had some training but not much. What guides it is no primer, but pure blood stream and formidable intelligence.

“Barbra short-circuits all the intellectual responses and goes directly to an emotional response,” says a friend. “She's the first singer of our generation who does what Europeans do with a song. She sings the emotion, not the music.”

“Judy, you felt sorry for,” says Kay Medford, mother to Miss Streisand's Fanny Brice in Funny Girl. “This one, you stand back in awe. I wish I knew how to make it more poetic, but ... it's like when you have the cap off the toothpaste and it just flows free. God, she's so free ... she's like the dancers. She's audacious. After Barbra, everyone else sounds old-fashioned.”

“She does my songs,” a forty-ish devotee said recently. “But not with maudlin sentimentality. She does them with a new jazz ring. She gives me the contemporary spirit, she gives me the nostalgia ... She gives me all of it.”

And what of the youngsters, the smitten swarms who want to look like Streisand, talk like Streisand, act like Streisand—in itself, a no more curious phenomenon than Beatle-aping? The plain ones with great visions anoint themselves in her success. The loners, the shy and awkward ones, feel the curious vulnerability she projects when she sings. The rebels feel her defiance—“Gotta get outa this town,” she intones darkly, and, oh, they know, they know. The misunderstood feel that grownups never understood her, either.

In the offices of Ellbar Productions (Elliot + Barbra: TV record and concert producing, music publishing, films, Broadway, management and merchandising—“That's where the corporation aspect of Barbra is,” an aide said) three members of the Barbra Streisand Fan Club, all from Brooklyn, gathered recently to pursue the subject further:

Stuart Lippner, 18: “The first time I saw her was on the PM East show. My mother came into my room and told me there was a nut on the TV who was giving the other guests some psychological test. Here she was, a nothing, telling important people they were schizy and all that. I liked her because she wasn't afraid of people bigger than she was. Funny thing, for a long time I didn't even know her name. We called her The Nut from TV.”

David Sherman, 18: “I think everything she did was premeditated. She wanted to look weird. It was a gimmick.”

Barbara Yanofsky, 17: “But she had to, because she couldn't look beautiful, so she chose to look different. What's wrong with that?”

Stuart: “Nothing. She made it work. I give her credit for it.”

David: “She gets across the feeling of freedom. Like life is too small for her and she wants to get out beyond—have more—and this is a repressed desire in all of us.”

Stuart: “She's so great. To hear her sing 'Suppertime' and 'I Had Myself A True Love,' you'd swear she lost a man. Yet we know that she has Elliot and that they are happy and secure. That's what a great actress she is.”

David: “I feel we are a part of the most important theater history of our time. One day I will take out an old corroded Playbill and I will be able to say, ' I saw her in Funny Girl.' It's like my mother always saying, 'I saw Laurette in The Glass Menagerie.' I'd like to see her do a straight dramatic role, like Catherine Holly in Suddenly Last Summer. She was like Barbra—everyone thought she was a nut, and she was the only sane one there.”

Stuart: “She reminds me of Shaw's Cleopatra. She has the same ability to charm people without beauty. She has ambition and will. Personally, I think her success will be greater than Cleopatra's.”

Barbara: “Let's hope she doesn't end the same way.”

Stuart: “She's done a lot for the Brooklyn accent. A lot of kids aren't ashamed of it any more.”

David: “She's done a lot for Brooklyn, too. People always used to say, 'Oh, you come from Brooklyn?' with contempt. Now we can say, 'Well, Barbra Streisand comes from Brooklyn.' Of course, personally we feel she's delighted to be out of Brooklyn.”

Stuart: “I think success has gone to her head. She won't even sign autographs any more. All the kids used to meet at the Winter Garden after school every day, but now a lot of them are moving over to Sammy Davis because he's more cooperative.”

David: “I think a little flop will change her, or maybe having a baby.”

Intruder: “Have you known her long?”

Barbara: “Known her! Are you kidding We've never even met her.”

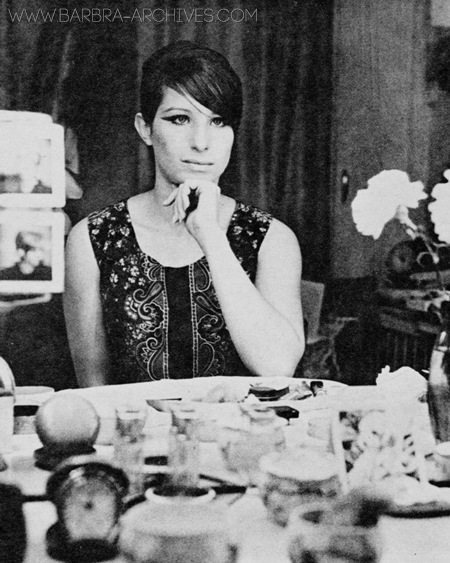

Miss Streisand sits pensively. A long, pale, elegant fingernail flicks through her hair—short now, and sleekly styled—and comes to rest at the corner of her mouth.

“These kids,” she says, “they want to meet me because I'm just like them. Like, I always wanted to meet Marlon Brando. I wanted to say to him, 'Let us speak to one another, because I understand you. You are just like me.'

“So one night I'm waiting to go on at a benefit, and somebody comes up behind me and starts caressing my should—you know—and nuzzling my neck. And I turn around, and there he is! It's Brando! And he says—you know, kidding—'I'm letting you off easy,' and I laugh and say, 'Whaddya mean, easy? This is the best part!' And then—I don't know—what the hell was there to say? It was kind of sad, because he wasn't just like me at all.”

End.

[ top of page ]