Holiday

November 1963

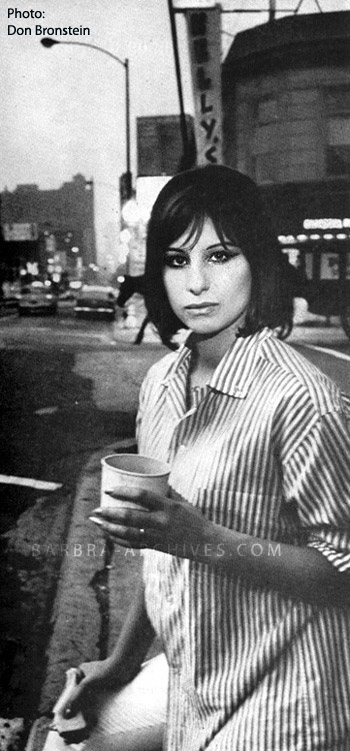

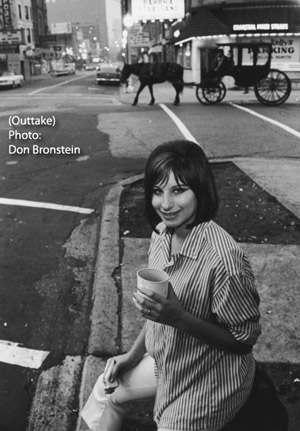

I REMEMBER BARBRA

by: Jerome Weidman

"The trouble with history," Scott Fitzgerald once observed, "is that you never know when you're living in it." This is true, but I am not altogether sure that it is a bad thing. All during the late war, for example, whenever I found myself in an interesting place where Things Were Happening, I became aware of a petulant inner voice saying to me: "Now, don't just stand there with your mouth open. Make an effort to remember everything you see and hear. This is an important event. This will be a part of history."

I always made the effort, mainly because I am a coward in the presence of inner voices. Oddly enough, however, now that almost two decades have separated me from those Things That Were Happening, it is rarely the events themselves I remember. It is almost always something peripheral, something small that I was not even aware I was observing — something my inner voice would have spurned — that had lodged itself indelibly in my mind.

"Ah, did you once see Shelley plain?" Robert Browning asked. "And did he stop and speak to you? And did you speak to him again?" The answer is yes, except that, in my case, it was not Shelley. It was a girl named Barbra Streisand, and it never occurred to me at the time that the meeting would be the part of that particular day that would become for me a moment of history.

Late in November of 1961, on a gray afternoon made grayer by my mood, I took a taxi from my doctor's office to the St. James Theatre. The doctor had just told me that, in his opinion and the opinion of a surgeon who had examined me the day before, I would be well advised to go into the hospital almost at once for an abdominal operation.

In five weeks, on January 2, 1962,I was scheduled to go into rehearsal with a musical play called I Can Get It For You Wholesale that Harold Rome and I had written from a novel of mine with the same title. My doctor and the surgeon felt it would be dangerous for me, and unfair to my colleagues, to enter this period of strenuous activity without surgical correction of my abdominal condition. No one enjoys being told he must go under the knife, and if you tell it to a man who is, by his own admission, a coward in the presence of inner voices, it should not be too difficult to imagine the mood in which I traveled across town to the St. James, where David Merrick, the producer of our show, had scheduled an audition.

It was not an important audition. Most of the cast had been chosen during the preceding weeks. What remained to be filled were a few minor roles. I could, without compunction or hesitation, have left the choice of actors and actresses for these remaining roles in the extremely able hands of my colleagues. There is something about the theatre, however, that converts you into a busybody. Or perhaps it is people who possess the instincts of the busybody who are attracted to the theatre. I don't know. I do know that it is as impossible to become partially involved with a show as it is to partially fall in love.

From the moment I became involved with my first theatrical venture, I became involved in all its aspects, about many of which I knew as much as Columbus, when he hoisted sail at Cadiz, knew about Chicago. I Can Get It For You Wholesale was my third show, and I would just as soon have left the filling of those remaining minor roles in the hands of my colleagues as I would have left in the same hands the correction of my abdominal outline.

My colleagues may have seen only another colleague in a gray mood coming down the aisle of the St. James that afternoon, but I knew better.

In the self-dramatizing inner mirror that is as indispensable to the writer as his pencil and paper, I saw a doomed man forcing himself to the treadmill of his daily task in order to conceal from his colleagues - who might, if they knew the truth, divert their energies from the joint effort - to the fact that he had just been sentenced to death.

This may seem an unfortunate mood in which to audition actors and actresses for minor comic roles. As it turned out, it proved to be the ideal mood. For more than two hours I sat in the darkened theatre, beside Mr. Rome, and behind Mr. Merrick's staff, brooding about my fate and my plumbing, listening to that petulant inner voice say, "Pay attention to your every emotion. Note carefully how you feel. It isn't every day a man gets told he is doomed. You may want to use it some day in a story."

I was aware, as I brooded, that things were happening on stage. None of these things was, however, distracting. There is a quality about all auditions, especially for minor roles in a musical show, that is not unlike the making of pancakes: each one is, of course, different from all the others, the way every set of fingerprints is different, and yet they are all very much alike in general condition.

First, of course, there is the blinding glare of the work light overhead. Everybody agrees, during all auditions, that it would improve matters considerably if somebody hung a shade or even pasted a piece of newspaper around that damned naked bulb, but nobody ever does it. Something about union rules, somebody mutters.

Then there is the stage manager who, at periodic intervals, appears from the wings and, into the dark cavern of the orchestra that conceals the author, the director, the producer's staff and a few other legitimate busy-bodies, calls out, "Miss Mishallevev Neurokumquat." Or, if he is introducing a male actor, he says, "Mr. Mishallevev Neurokumquat." The names of all unknown actors and actresses, when heard for the first time in a darkened theatre at an audition, sound like an anagram composed of letters taken from the sides of two or more Lithuanian Pullman cars.

If one of the busybodies happens to know the performer, or vice-versa - which is the case quite often, since people in quest of jobs in the theatre go from audition to audition the way Fuller Brush salesmen go from door to door - there is a good deal of delighted squealing, hysterical hand waving, and dubious punning, during which it turns out, always to the surprise to at least this busybody, that "Mishallevev Neurokumquat" is actually "Vicky Smith" or "Nicky Jones."

The director asks Vicky or Nicky or, more often, Mishallevev what he or she is going to sing for us. He or she tells us. There is a small fuss about the music. The size of the fuss depends upon whether the performer has brought an accompanist, or is going to use the all-purpose accompanist provided by the producer. The fuss ends. The performer sings. The performer stops singing. From the depths of the darkened auditorium the director says, "Do you have a ballad. Miss Neurokumquat?" Or Vicky. Or Nicky. She or he has.

Same fuss with the music. Performer sings ballad. If the performer shows any promise at all, the heads of the busybodies come together like the petals of a flower closing for the night, and a good deal of unintelligible murmuring rises into the shadows. This phase always ends with the director turning back to the stage and asking, "Do you dance?"

If the performer does dance, meaning if she is a professional dancer, she says so, then announces with whom she has studied and in what shows she has danced. If the performer does not dance, meaning she is not a professional dancer and has no talent in that direction, she always says, "Well, I'm not primarily a dancer, but I can move."

The director says, "Thank you very much." The performer smiles, says "Thank you very much," gathers her music, and goes off to the next audition down the street. The busybodies in the darkened theatre shift their buttocks, light fresh cigarettes, and the stage manager appears from the wings. "Miss Mishallevev Neurokumquat," he says into the darkened theatre.

When he said, it, on that gray November day, for perhaps the fifteenth or twentieth time, I was trying to remember when I had made my will, and wondering if it would be necessary, before I went into the hospital, to see my lawyer about adding any codicils. The stage manager's numbing syllables had scarcely died away, when I became aware that something unusual was happening on stage. Out of the wings, moving slowly past the stage manager, came not a performer but a far coat.

This is not, of course, a complete description. To describe what was oozing out onto the stage of the St. James at that moment as a fur coat is about as accurate as describing the North Pole as cool. Still, in times of stress, one clutches at straws. Holding onto that particular straw with desperation, my mind began to paw about for clarifying detail.

First, I grasped the color. The coat was a combination of tans, browns, yellows and whites, all swirling about in great shapeless splotches, like a child's painting of the hide of a piebald pony. Wondering if what I was watching was indeed the hide of a horse, my mind made its next discovery: shape. The flat surface that served as the body of the coat was adorned at the neck, the cuffs, and the hem by great fat rolls of not quite but almost jet-black foam rubber that looked like flexible sections of sewer pipe. Wondering desperately where I had seen this coat before, and knowing damned well it had not been on any human being who had ever walked a city street or a country lane in my presence, my mind finally disgorged the startling but satisfying answer: this was the coat worn by Michael Strogoff, The Courier Of The Czar, in the movie of the same name to which Miss Tischler had taken our 4B class as a Washington's Birthday treat when I was a boy of nine in P.S. 188.

With this much settled, my mind was free to record several other interesting details. Out of the bottom of the coat, helping - but only barely helping - to support it, protruded a couple of very shapely legs that ended in a couple of very dirty tennis sneakers. Out of the top of the coat stuck a ball of brownish steel wool, the kind one uses to scrub pots and pans, that might have been hair. Somewhere around the middle of the coat, where Michael Strogoff had belted his sword, something I could see no sign of a hand - was supporting a bright red plastic briefcase.

And, oh yes, the entire contraption was being tugged forward across the stage by a short leash which, on closer examination, proved to be a long nose.

The coat moved forward perhaps five feet. The red briefcase fell to the stage with a loud slap. The coat collapsed into an enveloping puddle concealing the briefcase, then rose slowly. For a moment the briefcase hung in the air, like a cotton ball caught in the spray of a bubbling fountain, then shot out in an arc, like an orange pip squeezed between thumb and forefinger. The fur coat changed shape. It hurtled up and out like a football player leaving the ground in a flying tackle, and caught the briefcase before it bounced. But then the coat bounced. It hit the stage, crumpled into a wad, then rose straight up into the air, all its rolls of black foam rubber billowing wildly, and from the bottom of the coat the pretty, sneaker-shod legs kicked and clawed, as though trying to get back to earth. They did, with a thump that sent the red briefcase out in another flying arc. It landed on top of the piano, burst open like a melon hitting a sidewalk, slid across the shiny wood, and showered a mass of sheet music into the startled face of the accompanist. The leash pulled the fur coat around to face the darkened theatre. Out of the wad of tangled steel wool came a twanging voice dripping with the ambiance of Bushwick Avenue.

"That guy is a liar," the voice said, and the coat jerked in the direction of the vanished stage manager. "My name is not Mishallevev Neurokumquat. It's Barbra Streisand. With only two 'a's. In the name, I mean. I figure that third 'a' in the middle, who needs it? What would you like me to do?"

Nobody answered. For a moment I did not understand why. Then I looked at Mr. Rome and my other colleagues. Tears were streaming from their eyes. From their mouths emerged meaningless whimpers. Their hands were clutching their navels. They were helpless with laughter. As for me, I did not realize until much later that, in the struggle to catch my own breath, I had, for the first time since I had left my doctor's office, completely forgotten that I was a doomed man.

The nose came forward, dragging from the depths of the foam rubber collar a face. It squinted down into the darkness with monumental distaste.

"What are y'awl? Dead or somethin'?" Miss Streisand demanded. "I said what would you like me to do?"

"Can you sing?" the director asked.

"Can I sing?" Miss Streisand said to the work light. The squint swung down toward us again, like a whip. "If I couldn't sing, would I have the nerve to come out here in a thing like this coat?"

"Okay," the director said. "Sing."

"Sing!" Miss Streisand said to the work light, and I wondered if all her friendships with inanimate objects took shape as quickly as this, or whether this particular work light was one with which rapport had been established long ago. "Even a jukebox you don't just say sing, you gotta first punch a button with the name of a song on it," Miss Streisand said irritably into the darkened theatre. "What should I sing?"

"Anything you want," the director said.

The squint gave place to a look of wide-eyed, childish astonishment, and it occurred to me that Miss Streisand was as pretty as her legs.

"Anything?" she said incredulously.

"Anything," the director said.

Miss Streisand turned to the accompanist and said, "Play that thing it's on top."

What proved to be on top may not actually be the funniest song ever written, but it certainly came out that way when filtered through Miss Streisand's squint, fur coat, gestures and vocal cords. It was what, as a veteran of many auditions, I have come to identify as a "Why?" song. Just as some novelists, trapped by the problem of exposition, frequently solve it by causing one character to feed leading questions to another, so some lyricists, facing the problem of how - in a medium that has already said it thousands of times - to say "I love you" in a new way, solve it by asking a rhetorical question, then go on to answer it. "Why am I so happy?" Because, stupid, I love you. "Why does the sky seem brighter today than usual?" Because, you idiot, today I met you.

Miss Streisand's song, traditionally enough, asked why she loved a boy named, if memory serves, Arnie Fleisher. The answer, however, was not traditional, because Miss Streisand, in the midst of making it, remembered that she also loved another boy. I do not know his name. Not because memory, usually so dependable, is not serving in this instance. The truth is I never heard that second boy's name. The words were engulfed in the laughter of the theatre professionals around me. When Miss Streisand had finished, and the theatre walls had settled back into place, the director was just able to honor the tradition of his trade: "Do you have a ballad?" he managed to gasp.

Miss Streisand looked at him as though she were in Aix, where she had been pacing about worriedly for days, and he were the boy who had just arrived with news from Ghent.

"Ooh, have I got a ballad!" she squealed. "Wait till you hear!"

She made a complicated flopping gesture in the direction of the accompanist, revealing for the first time a pair of slender, beautiful hands only partially disfigured by the sort of blood-red talons once popular with the artists who used to illustrate Sax Rohmer's stories about Fu Manchu. The accompanist, who was by now clearly under her spell, seemed to know exactly what Miss Streisand meant. From the tangled mess that had spilled out of the red briefcase, he plucked a sheet of music and struck a few chords.

Miss Streisand folded those lovely hands in front of that appalling coat, looked up toward the second balcony, opened her mouth, and an extraordinary thing happened.

Softly, in a voice as true as a plumb line and pure as the soap that floats, with the quiet authority of someone who had seen the inevitable, as simply and directly and movingly as Homer telling about the death of Hector, she told the haunting story of a girl who had stayed "too long at the fair." It was a song, of course, and a good one. But emerging through the voice and personality of this strange child, it became more than that. We were hearing music and words, but we were experiencing what one gets only from great art: a moment of revealed truth. This, you suddenly felt, is the way it is. This, you finally understood, was what T. S. Eliot had meant when he wrote that the world ends "not with a bang but a whimper." And this, you grasped as you wiped away your tears, was what people meant when they spoke of the X quality that makes a star.

Miss Streisand got the job, and I went to the hospital. There, after I came out of the anesthetic and discovered that my death sentence had been, in Mark Twain's phrase, greatly exaggerated, I was visited by my collaborator. Mr. Rome is a man of many talents. Not the least of these is an extraordinary capacity for friendship. He brought with him a bottle of whisky and news of our project. After we had made a small inroad on the former, he started on the latter.

"I've been thinking of this Streisand kid," Mr. Rome said.

"So have I," I said.

It turned out that our thoughts were not too far apart. Miss Streisand had been hired to play the role of a garment center secretary called Miss Marmelstein.

As conceived originally, in the novel I published in 1937 and in the play Mr. Rome and I wrote in 1961, the role of Miss Marmelstein is not exactly the focal point of the enterprise, and yet you've really got to have her.

The hero of I Can Get It For You Wholesale moves up in the world and, from doing business on the pavements, he begins to function in an office. To satisfy the most minimal demands of verisimilitude, any representation of an office must have a desk and a secretary. Mr. Rome and I had spent very little time writing in the desk, and not much more establishing the secretary. In our original script she was, like the desk, just another piece of furniture.

Until Miss Streisand, aged nineteen, came along.

"You let a kid like that come out on a stage," said Mr. Rome, who hates to be called a Veteran Showman, perhaps because he happens to be a Veteran Showman, "and things are going to happen. You keep her just a piece of furniture, saying things like Call for you, Mr. Jones or Here's those papers you asked for, Mr. Smith, and the audience is going to forget all about Mr. Jones and why he's getting that call, or Mr. Smith and why he asked for those papers. They're going to be watching that girl. Watching her and expecting her to do something. Unless we give her something to do - and it can't be something extraneous, it's got to be part of the story - unless we do that, the story is going to go out the window."

It didn't. Because Mr. Rome was right, of course, and we set about at once, using my incision as a temporary desk, giving Miss Streisand plenty to do. The way she did it is, as Frank Sullivan's cliche expert might put it, a matter of history: she stopped the show on opening night and every night thereafter.

Between those happy occasions and my first glimpse of Barbra at the St. James audition, our paths crossed frequently, about as frequently as the paths of a pair of Siamese twins set afloat in a sealed barrel on a turbulent river. Out of the eleven and a half weeks between the start of rehearsals and the New York opening at the Shubert Theatre on March 23, 1962 - a period that made, for at least one participant, the Battle of Cannae look like a quiet hour with Queen Victoria's Leaves From the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands - a number of moments with Miss Streisand loom up out of the haze of battle, moments that bring into sharper focus that first generalized impression and help to convert, at least for the author of these notes, a talent into a human being.

The first moment came, appropriately enough, on the first day of rehearsals. In a ritual as fixed by tradition as the moves in a minuet, the day started with the "first reading by the cast." Sitting in a half-circle on stage, the actors and actresses read the play to the authors and the director. It is always a time of curious intimacy. Everybody has the same feeling: please God, make it a hit! Other emotions will succeed this one, many of them revoltingly more intimate. But none will ever recapture that early fragment of shared innocence. It occurred to me, as I listened and watched, that the only person who was not sharing it with me was Miss Streisand.

As the others read their parts, as the director and Mr. Rome and I listened, I became aware that Miss Streisand was doing more than making the occasional note next to a line with which many actors and actresses punctuate the reading. Miss Streisand, scribbling busily, might have been racing the clock to get her translation of the Decline And Fall to the printer before other activities, such as rehearsing a musical play, claimed her attention.

When the reading ended, I watched her go up to the press agent and engage him in a long, animated conversation. It seemed to deal with Miss Streisand's composition, a good deal of which, to judge by the expression on the press agent's face, he found perplexing. I wandered across to them and, now a full-fledged busybody, asked what was happening.

"Get a load of this," the press agent said. "I asked the cast to give me some stuff for the biographical notes in the program. Look what this dame gives me."

He thrust Miss Streisand's composition at me. I read: "Not a member of the Actor's Studio, Miss Streisand is nineteen and this is her first Broad way show. Born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon, she attended Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. She appeared off-Broadway in a one-nighter entitled Another Evening With Harry Stoones. She has appeared at New York's two best known supper clubs, the Bon Soir and the Blue Angel, and was on Mike Wallace's PM East eight times, the Jack Paar show twice, the Gary Moore show, the Tonight Show with Groucho Marx, and is being sought for many top TV entertainments this season."

I looked up and said. "Was it hot in Madagascar?"

"How the hell should I know?" said Miss Streisand. "I never been to the damn place."

"That's my point," the press agent said. "It's a phony. Nobody reading that will believe you."

"What the hell do I care?" said Miss Streisand. "It's me I'm worrying about, not anybody reads the program. I'm so sick and tired of being born in Brooklyn, I could plotz. Whad I do? Sign a contract I gotta be born in Brooklyn? Who asked for it?"

"Don't you like Brooklyn?" I said.

"What's that got to do with it?" she demanded. "I hapna love Brooklyn, but it's like the name Barbara. Every day with the third 'a' in the middle, you could go out of your mind. I mean, what are we here for? Every day the same thing? No change? No variety? Why get born? Every day the same thing, you might as well be dead. I've had nineteen years Barbara with three 'a's' and all my life born in Brooklyn. Enough is enough. Don't you understand that?" ** [see note below]

I certainly did. I had been nineteen myself once.

"Where did you study singing?" asked Mr. Rome, who had joined us.

"Who had time to study singing?" she said. "Nineteen years, and I haven't even had time to get out of Brooklyn yet!"

Her conception of time was clarified for me a week later during a ten-minute rehearsal break. I spent five of those minutes discussing something with Mr. Rome, then went out into the lobby to make a phone call. There were two booths. Both were occupied and both had several people waiting in front of their doors. When the stage manager's whistle sounded the end of the ten-minute break, everybody in the lobby hurried back to the rehearsal. Everybody except me and, I discovered as the lobby emptied, Miss Streisand.

She hurried into one booth. I went into the other. It crossed my mind, as I dropped my dime into the slot, that while I would not be holding up anybody by returning late to the rehearsal, since I was not needed on stage, Miss Streisand was very much needed and would be holding up everybody. The truth of what had crossed my mind was confirmed a moment later.

"Barbra!" the voice of the stage manager came bellowing into the lobby. "For God's sake, on stage!"

Imperturbably, from the adjoining booth. Miss Streisand called, "Just one second! Be right there!" I thought the next sound I would hear would be the opening of the door of the adjoining phone booth, followed by Miss Streisand's footsteps hurrying back to her rehearsal. I was wrong. The next sound I heard was the ping of a coin dropping into the slot in the next phone booth, followed by Miss Streisand's voice saying, "Operator, get me Los Angeles, huh?"

What she got, in addition to Los Angeles, was a bawling out from the director that, even though I thought it completely justified, disturbed me. She took it head down, face concealed by a curtain of tumbled hair, while her hands made small twitching motions in her lap. After all, I thought miserably, she's only a kid. A couple of weeks later, the morning after the Philadelphia opening, I discovered that to describe Miss Streisand - who was clearly a genius, and even more clearly destined for the heights - as"only a kid" was not unlike identifying Savonarola as "only an investigator."

It had been a rough opening, and the reviews, which were not exactly uniform, reminded one of Mr. George Kaufman's definitions of the word "mixed" in the phrase "mixed reviews": "good and lousy." The director had assembled the cast at the back of the theatre for one of those sessions known as "notes." In the theatre this always means the same thing: the cast gathered in an uneasy cluster, sitting cheek by jowl as though to share their bodily warmth against the winds of a cold world; listening, in a manner that can only be described as "nervously scared sincere," to the notes the director has made on their last performance.

I had been on the phone with my agent in New York, assuring him that out-of-town critics had a tendency to overuse the word "disaster," and so I arrived at this particular "notes" session a few minutes late.

I do not know, therefore, if Miss Streisand had done anything special on this particular occasion to annoy the director, or whether the cold rage with which he was addressing her was due to nothing more than the tension under which we were all living plus our heroine's by now established talent for sabotaging any executive attempt at organization.

As the director's words went hurtling toward her like so many venom-tipped darts, the rest of the cast seemed to cringe away, as though afraid to be splashed by criticism so savage and so total that it might be permanently disfiguring even to those who happened to be in the neighborhood. My heart, which should have been sticking around to take care of its owner's bruises, insisted on going out to Miss Streisand.

There she sat, again head down, her face again concealed by that curtain of tumbled hair, her hands again making those small twitching motions in her lap. I was so upset by what was happening to this helpless sliver of a girl under the lashing of the director's verbal knout - after all, she was just a kid, wasn't she - that I almost committed what is in the theatre the equivalent of, at a royal level, turning one's back on the sovereign, namely, interfering in public with the director's total authority over the cast. I was saved from this sin not only by the fact that this was, after all, my third show and, as Mr. Phil Silvers once put it: "If you hang around, you learn!," but also, and in the main, because the sight of Miss Streisand's suffering filled me with so much pity and horror that I could neither speak nor move.

When the holocaust was over, I managed to pull myself together sufficiently to approach the stricken child. She was still sitting there, all alone now, the others having fled as though from a carrier of the plague, her head still bowed, her face still hidden by the curtain of hair, her hands still twitching spasmodically in her lap.

"Barbra," I mumbled, my voice shaking, "I'm sorry, kid."

Her head came up. The curtain of hair fell back, revealing not the tears I expected, but a puzzled frown that took me by surprise.

"Listen, Jerry," she said, and she lifted from her lap not only what her twitching hands had been doing while my heart had been bleeding for her, but also the pencil with which she had done it: the floor plan of a one-room apartment criss-crossed with innumerable sketches of furniture arrangements. She said, "I got this new apartment on Forty-fourth Street, and it's real nice, you know, but the damn fireplace, it's all the way over here on this wall. so where the hell would you put the studio couch, huh?"

I cannot remember if I told her. I would like to think, now that the campaign is over, that I did. After all, it is not often that one can truly say yes, one did see Shelley plain. And about almost nobody I have ever met nobody, that is. I have ever met who is nineteen - do I feel I can say with confidence: Barbra Streisand, like Shelley, is going into the record books.

Not only because she has genius, which I discovered on that first day at the audition in the St. James Theatre; nor even because she is what the lawyers call sui generis, or unique, which is what every star must be.

Barbra Streisand is going into the books, near the top of whatever list gets compiled, because she possesses one other ingredient necessary to stardom, and I discovered it on that dismal morning in Philadelphia: she is made of copper tubing.

END.

** Note: In 2014, when New York Magazine ran this quote in an issue dedicated to New York musicians, Streisand wrote the magazine to set the record straight:

“It simply isn't true. The truth is I didn't want to change anything about myself like my nose, my teeth, my clothes, whatever. But I wanted to have something original, so I took out the second 'a' from Barbara and became Barbra, which is the same name only without an A, and it looked a bit different and unique.”

Related Page: I Can Get It For You Wholesale, Broadway 1962