Vogue

August 1993

No woman in Hollywood has more talent or power than Barbra Streisand. She has conquered the stage, won an Oscar, and become a critically acclaimed film director. As she demonstrates again with her new album, she is also the biggest-selling female recording artist in the world. And she's a Friend of Bill. Yet no star is as controversial or, as JULIA REED learns, as vulnerable to criticism.

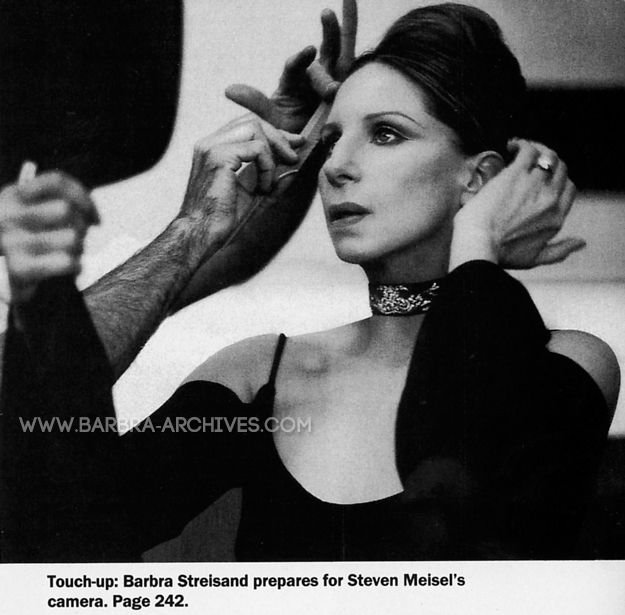

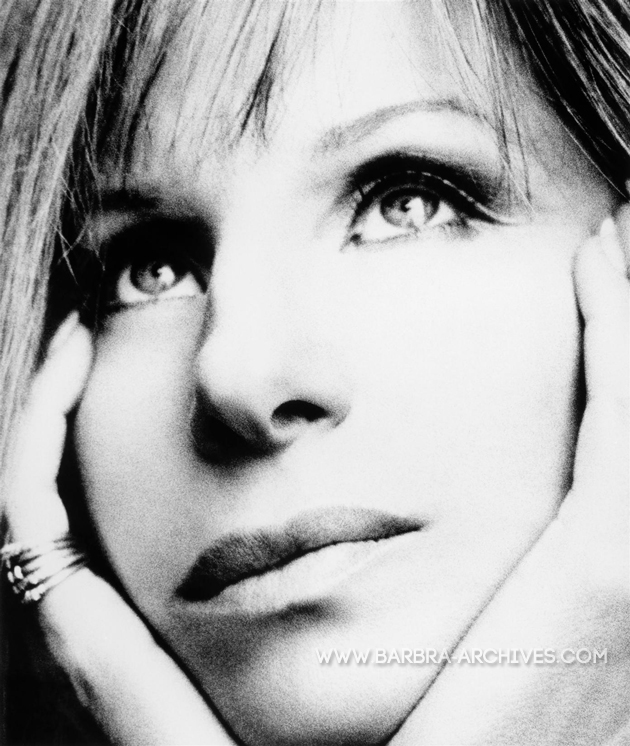

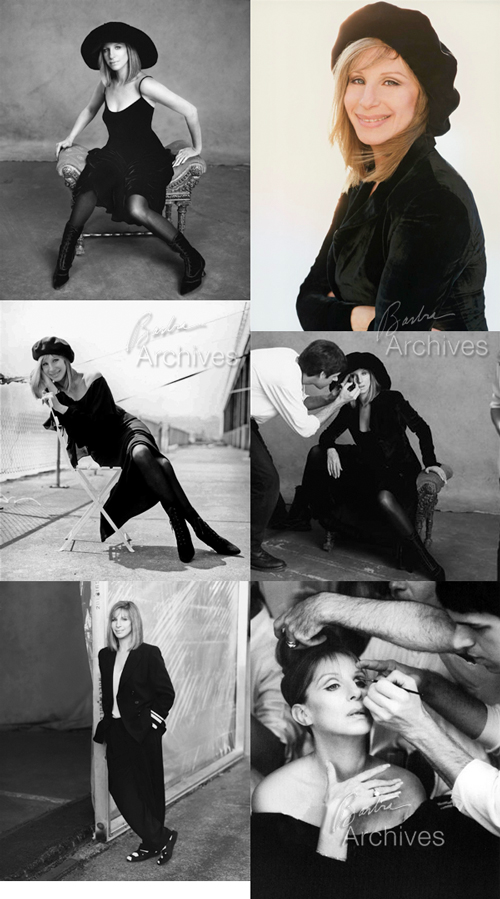

Photographed by STEVEN MEISEL.

Evidence of Streisand's shift away from her once-reclusive ways: her very public best-friendship with Donna Karan. She wears the designer's romantic tribute to the Victorian era, OPPOSITE PAGE - an extravagant velvet picture hat and an ankle-skimming coat. Hat (about $445) and coat (about $1,650) by Donna Karan New York. Bergdorf Goodman. Hat also at Nordstrom, San Diego. Coat also at Saks Fifth Avenue, NYC; Neiman Marcus; Nordstrom. Details, more stores, see In This Issue. Fashion Editor: Grace Coddington

I am sitting in Barbra Streisand's enormous apartment on Central Park West, in a room—one of her many studies—decorated almost entirely with Stickley furniture (one of her many obsessions), and we have been talking a long time about everything from plastic surgery (she is too frightened to have it done: "I don't even have pierced ears") to her taste in art ("I love pregnant nudes; I love mother-and-child paintings"). But it is late spring, just after her much-documented trips to Washington, so we also talk—a lot—about the fact that she has become a lightning rod for all the criticism dumped on "insulated and bubbleheaded" movie stars and their involvement in politics in general and the Clinton White House in particular.

This is merely the latest item on a list of slights Streisand has suffered and cataloged since her career's inception, but she is genuinely perplexed, hurt, indignant. "Why, why do people do this?" she asks over and over to the point that it becomes a conversational tic. Why can't people just accept her, like her, leave her alone if they don't? she wants to know. And I begin to wonder the same thing about this intelligent, honest, and right this minute, barefoot woman with no makeup in a fuzzy blue bathrobe, a phenomenon—overpowering even with damp hair—but still awfully, awfully vulnerable, still seeking approval and often not getting it after more than 30 years in show business and 51 on earth.

Streisand is famous for protecting herself by running a tape recorder in tandem with that other interviewer, but (perhaps to proclaim the newfound security she is trying to convince both of us she now possesses) today there is none, so she utters into mine a line that has become her new mantra: "Whatever's said about me is said, you know. I can't control it. If one does good work, that's what stands the test of time. That's what lasts. The rest doesn't matter."

This "it doesn't matter" stuff is as hard won as it is tenuous. But she's giving it a try, putting herself out there, suddenly maintaining a higher public profile than she has in the last 25 years. Within the past year she has sung twice in public (both times on behalf of Bill Clinton), something she has done only two other times since 1967 when she received death threats from the PLO before a free concert in Central Park. She has signed a much-publicized new contract with Sony, giving her up to $60 million for movies she will produce, direct, and/or star in under her Barwood Films banner, as well as for eight albums, which will also earn her royalties of 40 percent on every wholesale unit sold. She is currently looking at scripts for her next project. The Normal Heart, Larry Kramer's controversial love story between two men in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, which she will produce, direct, and probably appear in. And, most staggering for such a famous recluse, she tells me almost in passing that she "probably will do a world tour. I want to touch the people and allow them to touch me. It's a way of going out into the world literally."

Already in just one week in May she was on the front page of The Wall Street Journal defending her political activism that had a few days before been disparaged on the front page of The New York Times; she posed for Vogue for the first time since 1975; she attended a listening party for her new album, Back to Broadway, at the Eugene O'Neill Theatre that also served as an AIDS benefit and where she accepted an award, a huge plaque commemorating the release other fiftieth album (she is the top-selling female recording artist in the world); and she actually went out to a dinner party. "I have a hard work agenda, but normally, socially, most of the time, I would just stay home. Now I'm trying to push myself out in the world."

She is the most powerful woman in Hollywood, and she's finally acting like it—in addition to The Normal Heart, she has bought film rights to Jeffrey Potter's book about Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and Patricia Bosworth's biography of Diane Arbus; has optioned the story of Lt. Col. Margarethe Cammermeyer, the lesbian who was forced to resign from the Washington National Guard; and is slated to star in and probably direct The Mirror Has Two Faces, a romantic comedy she says is "about the illusions of love, pragmatism versus romanticism," possibly with Harrison Ford. For more than 20 years she has has been one of the Democratic party's biggest fund-raisers, and she's at last acting like that too: accepting invitations to sleep in the same bedroom the queen of England did, while advising the administration on how best to market the as-yet-unveiled plan for national health care; attending both the Gridiron Dinner and the White House Correspondents' Dinner, the two biggest and most photographed media/politics fests of the year; going to dinner - in a restaurant, which she never does - with Attorney General Janet Reno ("I mean, two women who are interesting to each other want to get together and talk about life ... I thought it was exciting").

None of this would be a very big deal except that for Barbra Streisand stepping out usually means stepping into the fire - a pattern that has dogged her since her very first Hollywood outing, a "debut" party given for her by Funny Girl producer Ray Stark. Brando was there and John Wayne, and she was scared, so she arrived a little late, and she was shy, so she kept to herself at a table, and everybody said she was aloof and arrogant and the press reported it the next day, and overnight she got stuck with labels that in almost three decades she has not quite been able to shake. So she pulled in, spending time with close friends in one other seven houses (one in Beverly Hills, one in Manhattan, and five in one spot in Malibu—she bought or built all the houses around the first one she bought so no one else could). And she worked, making 50 albums and fifteen movies, sticking with the theory she keeps voicing that the work will win out. "The people have kept me a star for 30- some years because there's a truth to my work and that's what they get. And if I keep telling the truth, I can't get hurt."

She does get hurt, of course. She tells me so in practically the next breath ("I cannot bear the stereotypes people put on me. They don't allow for the anxiety, the vulnerability. It is a horrible feeling to be misinterpreted, misquoted, misjudged"), but she is right about the work. I once argued with a man I know, a musician, for 20 minutes as he told me why her voice is so perfect and powerful and how nobody else could carry the musicals that she has made her own. He pointed out phrases and notes, and I said, "Fine, but she still doesn't move me; I don't get the much-vaunted Barbra Streisand goose bumps." And then I watched maybe three minutes' worth of a montage from a Barbara Walters Special—Streisand singing "Happy Days Are Here Again" on her first TV special, Streisand in Funny Girl belting out "Don't Rain on My Parade," Streisand in the studio recording "If I Loved You" for The Broadway Album—and I had to call the musician up and apologize for being so hardheaded and tell him he was right, there is no escaping the power of this woman. She gets you even when you don't want her to; she gets you when you least expect it. Like in What's Up, Doc? when Ryan O'Neal pulls the drop cloth off the piano and she's lying there on top of it and she starts to sing "As Time Goes By." Or in Yentl when she unbuttons her shirt and Mandy Patinkin realizes she's a girl. Or in The Prince of Tides when she goes beyond the script and has Nick Nolte cry.

A dedicated collector of elaborate Art Deco clothes, Streisand shows off her more casual side in a classic double- breasted jacket and fluid trousers. DKNY jacket, about $395. Bergdorf Goodman. Donna Karan New York wool pants, about $650. Nordstrom.

She won two Grammys for her first album; an Emmy for her first TV special; an Oscar for her first appearance in a movie, Funny Girl. She was the first woman to produce, direct, write, and star in a movie, Yentl, and the first female composer to win an Oscar, for her song "Evergreen," from A Star Is Born, which she also produced. Thirty of her albums have gone gold and 20 have gone platinum, including the latest one, based on advance orders alone, even before it hit the stores.

But: "I still don't think of myself as powerful. I'm saying, look, everything I do is still a struggle. It took me years to get The Normal Heart financed. It took me years to get Yentl made. I couldn't sell The Prince of Tides to any studio. I had to give up all my percentage points. So I do not perceive myself as this powerful person."

Tides not only got made, it was an enormous box office success and won Nick Nolte his first Oscar nomination, but Streisand did not even receive a nomination for her directing, and that still hurts, at least as much as the fact that Yentl was not nominated in any major category. She has been extremely vocal in her opinion that she has to struggle and that she doesn't win because she's a woman in a town that expects women to be passionate about men but not about their work. She says women are equally hard on her "because they don't have the same opportunities as men, so they're still fighting to get to the top of a pin, and they don't realize that every woman's victory makes it easier for another woman." In the beginning she was "naive," in that she "could never imagine people being jealous and therefore negative on purpose," and she says that she "was shocked when she realized that that's true." She adds—giving me a level look with those laser eyes—that "there are women who are competitive and jealous and write mean things and distort what you say"; I tell her I have no intention of doing that, and she says, "Well, there are women who do" and tells me that "the truth is I didn't give an interview for eight years, Julia; I didn't give an interview for eight years, because something I said was taken out of context."

Now, I realize that this is a warning of sorts, but it's also fairly amazing—eight years is a long time to be silent over one article, so I ask her what happened and she says she had told the Los Angeles Times that Steven Spielberg had looked at the finished version of Yentl and that he had told her, "Don't change a frame." And the L.A. Times wrote only that she had gotten "advice" from Spielberg but not what it was. "I was so devastated by what they did, by how they tried to diminish me as a woman, that I did not direct a movie for eight years. So devastated that I actually forgot it.... I forgot the pain of it. You know how people block out the pain." It came back to her in her dreams while she was at a psychological seminar of sorts she occasionally attends. "And the pain was enormous when I thought, 'How did they leave out the advice?'... It was like saying, 'Well, this woman couldn't have done it without the help of a man.' The man saw a finished movie. You know what I'm saying? It just doesn't make any sense. So I didn't give an interview for eight years."

Streisand's reactions seem less extreme when you realize that most of them stem not just from the genuine unfairness of much of the flak hurled her way but from the need for approval that has frustrated and driven her all her life. It didn't matter that she knew what Spielberg said about Yentl. Her "devastation" derives as much from the omission of what would have been a high public compliment from an astoundingly well respected colleague as it does from the fact that her achievement as a woman was undercut. Currently she is furious with The New York Times in general and Maureen Dowd in particular for writing that she spent her time at the White House Correspondents' Dinner (where she once sang for JFK, which is why she wanted to go again) talking to Colin Powell about Bosnia. In fact, she says that she has known Powell since they met at an American Academy of Achievement Award banquet a year ago, that "he's a guy from the Bronx, I'm a girl from Brooklyn," that they were just friends making small talk. "I don't know about Bosnia and I don't talk about things I don't know about at all." But again, her anger is as much about the fact that her conversation was misrepresented as it is about the fact that the lead of that story features Michael Douglas and not Streisand as the star that "eclipses" the president. "Did you see The Washington Post after the dinner?" she asks me. "I mean, I was like a little girl, thrilled, you know. There's my picture with Colin Powell and one of the articles said, 'Streisand Turns Heads of State' and another is 'Barbra Steals Show at Correspondents' Gala' and another is 'Barbra's the Main Event' or whatever, and this woman at The New York Times acted as if she never read those articles. Why does this woman do that? It disappoints me in women."

During the course of our conversations, she tells me apropos of not very much that on Barbara Walters's first-ever TV special in 1976, she and then-boyfriend Jon Peters shared the billing with only one other couple, the president-elect and Mrs. Jimmy Carter. "Isn't that funny?" Twice she tells me that her guide at the Library of Congress kept asking her if she'd like to see the "like 118 entries of my music and stuff" that the library possesses, explaining that of course she wasn't interested in looking at them, opting instead for Jefferson's drawings of the Capitol dome because she is "very interested in architecture." She tells me about "the many components other nature"—the "glamorous side, the funky side, the waif, the sophisticated side, the tough side, the very vulnerable" one. She describes her Art Deco house, one of the five in Malibu, and the work she put into it (it has only two color spectrums, gray to black and burgundy to rose, and even the clothes in the closets match; she designed the motifs on the tile that covers the floor and the walls; she designed a case holding a collection of Art Deco objects as well as a necklace inside). And then she has her L.A. office fax a letter, which she reads to me out loud in its entirety, from a professor who stayed in the house with his wife, a Jungian analyst who was giving a seminar for Streisand and her friends. In the letter he calls the house "a living museum, surely one of the greatest of its kind in the world," and the pendant she designed "a quintessential piece of Art Deco jewelry." By the end of this tour de force, in which appearances are made by Nietzsche, the ancient Egyptians, the Aztecs, and Jung, he compares Streisand—albeit "archetypally"— to "a temple priestess, perhaps of Isis," and warns her not to be "too obsessed by the resistance of her critics," who are "all too human."

All this would border on serious self-aggrandizement, except it's so ingenuous, so naive, so needy that it's touching. "Isn't that gorgeous.... Wasn't that worth listening to?" she asks of the letter—not the first that she has made public. The Prince of Tides author Pat Conroy wrote in her copy of his book that "you're many things, Barbra, but you're also a great teacher... one of the greatest to come into my life"—an inscription she later included in Columbia's brochure promoting the movie. She craves endorsement. Denied it by the Academy, most of the press, and early on, her mother, she'll take it from Spielberg, the professor, Conroy, the Library of Congress.

As a child she "lived in an imaginary world" and dreamed not of being rich or famous but of being "liked" and "understood." Her father, an English teacher, died when she was fifteen months old, and she has told countless interviewers that her stepfather, whom she despised, never talked to her except for once when he asked her why she couldn't be more like one of her girlfriends, quiet. When Mike Wallace made fun of her for this on 60 Minutes, when he said, "Your step- father didn't talk to you? Come on ..." like what's the big deal, she said she was "in shock, I couldn't even talk," so she broke down and cried. Obviously it is a big deal for her, as is the fact that her mother did not have the capacity to make up for the loss of her father or the callousness of her stepfather. When she was thirteen, her stepfather left and she was relieved but also "mad that [her mother] had allowed this abusive behavior."

It is, she says, the same story as The Mirror Has Two Faces, "an interesting story about women and mothers and daughters and how a mother is responsible for the daughter's self-esteem and what happens when the mother doesn't give it to the child. The child does not have it, and she spends her whole life trying to disbelieve the myth." Barbra's own mother told her she had a so-so voice and should try to get a job in the school system, and to this day Streisand prefers making records to performing live because "it is private. You don't have to be judged instantly."

Her real father comes up in conversation constantly, touchingly, as in "I'm good at math, like my father" and "I love to be around academicians, scholars. Maybe it's because my father was a teacher." Some of the people closest to her lost their fathers in childhood: Donna Karan, whose clothes she wears almost exclusively and from whom she is "almost inseparable"; Jon Peters, for nine years her live-in boyfriend and sometime business partner; even, she points out, Bill Clinton. She has no photographs of herself with her father, but among her most prized possessions is a love poem he wrote to a girlfriend when he was nineteen, before his marriage to Streisand's mother. The recipient, now in her eighties, reached Streisand a few years ago and sent her the poem, which spells the woman's name with the first letters of each line. "Can you imagine what I'm telling you?" Streisand asks me. "It's a love poem written to her... about how love conquers all." She tells me she recognized his handwriting as soon as she saw it because she had some of his old postcards and that she is going to have the poem preserved by the process they told her about at the National Archives, the same one that enabled her to hold a letter written by George Washington in her hands. And then she tells me about a dream she had a few nights before, in which she was "in a galaxy in a universe" and she looked down and there was "a whole other complete galaxy" below. "It was telling me about going into the depths of me and that there was so much more to explore underneath. That's what it said to me. And my father wrote this poem and the beginning is about how he's sitting on a moonbeam looking at the world below."

That she would share such an intimate possession, not to mention the dream, with me, a relative stranger, illustrates the essential dichotomy in Barbra Streisand's life and explains at least partly why she is open to so much criticism. She craves privacy, but her desire for approval forces her to expose herself, and then she is labeled an egomaniac or a diva. She wrote the liner notes for her recent CD collection, a sentimental 96-page "personal scrapbook," and one critic wrote, "In each anecdote, color her heroic." But she means all that stuff; she is genuine and animated in her sharing of the stories and the letters, which she carries around like talismans. She uses them as she uses therapy and Jungian analysis and all the psych seminars she attends—to make sense of her life, so much of which has been lived on the public stage.

After all, she was a full-fledged star by the time she was 20—a big leap for a girl from Brooklyn who never knew her father and never even had a real date. "I was a personality before I was a person," she told Barbara Walters in 1985. "I never had an adolescence." And when she finally did have it, everybody was looking. We knew her hairstyles and her boyfriends; we watched her political evolution (her first "political" film, Up the Sandbox, about abortion and women's choices, was also the first developed by her own production company) as well as her emotional one. Streisand told Walters, "I've just gotten past my adolescence now." Eight years later she says, "I am still not where I want to be. I don't think one is until one dies, you know. Of course, I am still trying to find out things about myself. I want to be more loving, more compassionate, because I have a tendency to be cut off and not allow feelings in, and it's something I really strive to change in myself."

To that end, she writes down her dreams and watches for signs—when she was deciding between making The Prince of Tides and building an Early American dream house, she woke up in the middle of the night to find that the light above a painting in her bedroom had come on. She decided that the message was "Light up your art" and made the movie. It may sound wacky, but what that really means is that she will use any mechanism to find her own voice. She says the only mistakes she has ever made come from not trusting her instincts. They are—despite the psych jargon and Joseph Campbell-speak that occasionally dominate her vocabulary—what have always guided her, and they are also what give her a reputation for being difficult. She is driven to perfect her own vision—whether it's other houses or her movies.

It usually pays off. She says she was afraid of casting her son, Jason Gould, as Lowenstein's son in The Prince of Tides—"I thought deep, deep down, well, it's dangerous. We could both get attacked for this"—but the critics loved it. She chiseled Nick Nolte's body down and literally forced his emotions out, and he was nominated for an Oscar, which he credits at least in part to Streisand's "great vision." "It was the first time I had worked with a woman director. In working with male directors, I've found that the male actor and male director have a kind of collusive attitude about the emotional points of scenes. With Barbra, there is a lot of continued exploration."

Streisand opens up. She wears Donna Karan's latest take on the "cold shoulder" dress, a dramatic sweep of stretch velvet that flares through the shirt and the sleeves. Dress, about $995. In this story: hair, Garren of Garren, NYC, at Henri Bendel; makeup, Denise Markey for the Stephen Knoll Salon.

That she is true to herself has made her friends extraordinarily true to her. Lyricist Marilyn Bergman has been a close friend for almost 30 years. She met Cis Corman, her close friend and partner in Barwood Films, when she was fifteen and they were in the same acting class. Her ex-husband, Elliott Gould, father of Jason, professes not only to love her but to worry about her still. Ex-beau Jon Peters pushed Columbia to finally back The Prince of Tides and hosted a $200,000 fiftieth birthday bash in her honor featuring fire- eaters, circus animals, a Velcro wall, and face painters. Ex-beau Richard Baskin, the ice cream heir and composer of film scores with whom she was involved for a time in the eighties, was her date to the White House Correspondents' Dinner.

She says she is very close to Jason, now 27 and an independent filmmaker: "He's very much like me." Jason says his mother is "a perfectionist in everything she does" and acknowledges that she is criticized for it. "It seems ridiculous that you can get criticized for caring too much about your work." It is a sentiment that has been echoed by Jule Styne, the Funny Girl composer, who contends that "her reputation for being difficult comes from untalented people misunderstanding truly talented ones. Because she is so talented, she had a tendency— maybe she still does—to show off a bit."

The one area where she really hasn't shown off has been the political arena, despite the recent media flurry. In fact, she has been politically active since before most of the people who currently work in the White House were born- she raised money for Daniel Ellsberg's defense in the Pentagon Papers case; she sang for George McGovern during his 1972 campaign. Her first Democratic fund-raiser, in her own backyard in 1986, at which she gave her first concert in almost 20 years, netted $1.5 million for six senatorial candidates, five of whom won. Her charitable foundation, the Streisand Foundation, has given away $7 million worldwide since its inception seven years ago, mostly to groups that focus on AIDS, the environment, and civil rights; and groups like Project VOTE!, which educates, registers, and turns out low-income and minority voters, people who generally vote Democratic, for which the party should be grateful. Immediately after the 1992 L.A. riots, she forked over more than $ 100,000 to area charities just on her own, and after the 1990 Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska, when she heard that the tiny public radio station near the spill had lost its funding and was going off the air, she sent it enough to keep broadcasting. Last fall she risked the anger of her Aspen-addicted colleagues when she spoke out against Colorado's antigay Amendment 2. "Now, I'm willing to go out on a limb, you know, and say what I believe. And if it turns some people off and people don't go to my movies or buy my records, then so be it. It has to do with my involvement in the real world. Doing movies is about making your own world. You can control it. The real world you have no control over except in these little ways. Just by my saying something about Amendment 2, it gets national attention."

During the nuclear freeze era, she became a student of sorts of physicist Marvin Goldberger, then-president of Cal Tech, who had worked on the Manhattan Project; now she has gone back to the writings of Thomas Jefferson. (Inspired by Monticello, she is redecorating her Manhattan dining room all in white.) She says she has loved being in Washington for the first time as a tourist, was so excited to look at Jefferson's drawings at the Library of Congress, could not get over holding George Washington's inaugural address "in my hands" at the National Archives. "It's just very exciting to feel my roots as an American," she says. "I just feel so patriotic."

This same kind of breathless patriotism, big- time fund-raising ability, and earnest desire to be informed landed Pamela Harriman an ambassadorship to France. Barbra Streisand gets a cartoon depicting her voice coming out of the Pentagon: "Bill and I think you ought to be doing more for the whales. Do you have a problem with that, General?" At the inauguration, Aretha Franklin wore not one but two politically incorrect fur coats, and Hillary Clinton made a temporary transition from working woman to prom queen and nobody mentioned it. But when Streisand raised the fashion level by about 1,000 notches and came out in a great- looking Donna Karan pin-striped suit with a slit up the long skirt and some cleavage peeking out of the low-cut neckline, no less than the op-ed page of The New York Times blasted her for wearing "peek-a-boo power suits" in an article by Anne Taylor Fleming so over the top it almost had to be personal. No matter that the gala at which she wore the offending ensemble raised more than $8 million to offset the costs of the inauguration, a price CBS paid for broadcast rights only because Streisand had promised to sing.

But now she's blasting back at her detractors rather than pulling in. When she and her Hollywood colleagues were invited to the White House to attend a briefing on health care policy, The Washington Post's Jonathan Yardley accused her of passing herself off as a "political savant." She responded that she does not pretend to know about health care, that she went to the White House at the president's request to talk about what she does know, "communications, marketing," and about the possibility of her narrating a documentary on "the health problems of American citizens." She is furious that the Hollywood group received a lecture about their relative stupidity from James Carville—"You do not talk to Sid Sheinberg [the head of MCA] like that.... We have a right as an industry, as people, as professionals, to be taken as seriously as automobile executives"— and she says the idea that Hollywood is trying to "dictate policy to the White House" is "absolutely a joke."

Her response paid off. Both The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post wrote favorable pieces defending her and listing her credentials. The day after those pieces appeared, she called me back, saying she had only a minute to talk, and spent almost 60 telling how happy she was about the pieces and that the other night she had attended a dinner party where almost everybody was a Republican and she argued her point of view. When somebody asked her how she had the courage to do it, she repeated her mantra. "Because I don't care what they think. I have much less fear."

It may sound like a small victory—speaking your mind at a dinner party—but it's part of the new Barbra Streisand policy of engagement. This is, after all, a woman who has by her own admission never known how to have fun. "We didn't have fun when I was growing up. I was never taken anywhere." She jokes that she "went with Jon Peters because he knew what to do on Sundays," but now she's ready to figure it out on her own. It may take a little time—when a friend set her up with a blind date for a dinner, she never talked to him and spent the whole evening talking to Arthur Schlesinger instead. But she hangs out in the Hamptons with Donna Karan, she goes to Washington as a tourist she goes antiquing in Virginia, she says what she thinks and does what she wants and tries to convince herself she doesn't care what people say. She may even sing again, live, around then world. "I want to have more fun. I'm willing to take those chances now, you know, to live life to its fullest."

End.

Meisel Outtakes

Steven Meisel took some *gorgeous* photographs of Barbra for this issue of Vogue. Here are some outtakes, not used in this magazine, but shot during the same session. The photograph of Barbra on the chair was utilized in her 2006 concert tour program. Some of the others appeared in other Streisand tour programs.

[ top of page ]