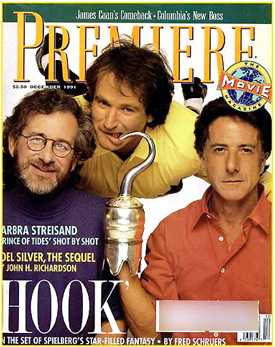

Premiere Magazine

December 1991

SHOT BY SHOT

Barbra Streisand uses a flashback sequence to provide the emotional underpinnings for Nick Nolt's character in 'The Prince of Tides'

by Nancy Griffin

AS A SUPREME HYPHENATE, BARBRA STREISAND WAS FULLY prepared to carry a heavy load as the director-producer-star of her new film, The Prince of Tides. But she never expected she'd have to literally labor under the weight of her once-bulky leading man Nick Nolte. Lucky for her she had asked him to lose 30 pounds for the role, because when it came time to shoot their love scenes, he insisted on verisimilitude. Streisand recalls that as she staged one firelit tryst for the cameras, "he was making me crazy laughing because he kept wanting to really do things. And I'm saying, 'No, no, no, cut! Cut!' You know, he gets carried away and goes, 'I really have to be on top of you, blah-blah- blah.' He was supposed to have just had an orgasm, and I'm saying, 'Jump on the side there,' and he goes, 'No, I have to do it on you.' " So which was it? "As a director, honey, I serve my actors," she says, laughing, "so if he had to jump on me, he had to jump on me."

She may be kidding, but the lengths to which Streisand went (supine or otherwise) to help Nolte create a role that has Hollywood humming about his first Oscar nomination are no joke. Streisand streamlined Pat Conroy's novel to home in on the story of Tom Wingo (Nolte), a South Carolina high school coach whose mid-life torpor is threatening his marriage. Streisand costars as Susan Lowenstein, Manhattan-based psychiatrist to Savannah Wingo, Tom's troubled twin. It is Savannah's suicide attempt that brings Tom to New York City, where Lowenstein quizzes him in an attempt to root out Savannah's malaise. Those office sessions lead to self-discovery for Tom and, in time, more recreational pursuits. ("Her questions made me as dizzy as her perfume," says Nolte in a gravelly voice-over.)

Streisand's aim was to help Nolte create in Tom both an irresistible romantic figure—"I want women to swoon over him," she says—and a complex psychological portrait. "This is a story about a man's journey, a man who has to learn to grieve," she says. Tom and his sister are tormented soul mates, suffering from long-buried childhood traumas. To illuminate the source of their pain, Streisand designed a series of flashbacks that build to a dramatic catharsis as Lowenstein leads Tom through a revisitation of his early family life.

Streisand was eager to travel back in time cinematically, although that device has defeated many a filmmaker. "I love the form of flashback—I've been obsessed with it since I was really young," she says. Even so, as she stepped behind the camera in June 1990 to film her first flashback, a dinner-table sequence that vividly establishes the Wingo family's dysfunctional dynamics, "I was petrified—are you kidding?" It happened to be her first day on the job as a film director since Yentl, and as she assembled her cast and crew on a sweltering set in a school gymnasium on location in Beaufort, South Carolina, "I'm going, 'I haven't directed in eight years. Jesus Christ, what if I don't know what I'm doing?' "

As The Prince of Tides' producer, she could have scheduled something a little, um, easier to kick off shooting. Not only was the flashback an emotionally charged ensemble scene, it featured four notorious filmmakers' headaches: three children and one dog. But Streisand had conceived the flashbacks as the psychological spine of the story and felt they needed to be completed first. "I figured, 'Get the hardest thing over with fast.' It was also a money problem, but the main reason was that I wanted the flashbacks to have occurred and to be in all our hearts, in our minds, when we shot the next scenes."

Had she wanted something easy to do, Streisand would not have dedicated her formidable talents and determination to making a big-screen version of The Prince of Tides. Conroy's 567-page best-seller is an epic family melodrama, dense with subplots and secondary characters. Fans of the novel—Streisand became one when it was published in 1987—adore its psychological reverberations as well as its flowery language. "It touches a lot of people where they live," she says, "in their guts, somewhere that's deep."

Conroy, who cowrote the script with Becky Johnston, has been unusually lucky with Hollywood adaptations of his novels; he says he's happy with the film versions of The Water Is Wide (renamed Conrack for the screen), The Great Santini, and The Lords of Discipline. But he proclaims himself most thrilled with Streisand's effort. "I was simply blown out by this movie," he says. "What you hope for, when they translate it into this form, is that some magic is retained. And she got it."

While the style of the film is a throwback to old-fashioned Hollywood romanticism, its subtext of healing the inner child taps right into the Zeitgeist of the '90s. "It's a film about forgiveness," says Streisand, "about saying, 'I need to love my mother and father in all their flawed outrageous humanity.' I chose to put that line at the end, because I felt this is the lesson of the movie."

The Prince of Tides has taken some typical Hollywood twists and turns. Before the book was even published, producer Andrew Karsch set up the project at United Artists in 1986; Conroy wrote a script that was subsequently revised by Jay Presson Allen. When Robert Redford got the scent and jumped in as a possible Tom Wingo, two more drafts were commissioned from Joan Tewkesbury and an unknown writer named Becky Johnston.

Having looked for a project to reunite them for the first time since The Way We Were, Streisand and Redford discussed co-starring in the film. "We loved working together," she says. But Redford, characteristically, was on the fence, while Streisand's desire to make the film burned more fiercely by the day. "He couldn't commit to it," she says. "You know, he's like Warren Beatty— they don't commit. It's like my life, I would become an old lady—but I can't wait around anymore. And then he was kind enough to just give it to me with his blessings."

Streisand's resolution to direct The Prince of Tides sprang from an impulse as undefinable as it was undeniable. Why had she taken an eight-year hiatus from film directing? "I never found anything I loved with a passion," she says.

And the critical heat she took for Yentl, her five-year labor of love that won Golden Globes for Best Musical/Comedy and Best Director and precious little from the Academy, has made her wary of putting her hand near the fire again. "I get attacked a lot for who I am rather than what the work is about," she says. "I thought women were very cruel about Yentl. Not the men, the men were very perceptive. And there were some great reviewers, like Pauline Kael and Sheila Benson—but some reviewers, it's like they attacked me for directing, acting, and producing. I couldn't understand that. Why didn't they talk about what the movie was about, how it celebrated women?" Consequently, "it makes me, like, go away. It's like 'Oh, who cares? I don't need this.' I don't know, I get very lazy, I don't make too many movies. I like designing houses, and I like just not working. Because when I work, I become so obsessed that I have no other life, practically."

When UA began to falter, Streisand found a new home for The Prince of Tides at Columbia and a guardian angel in her old pal Jon Peters. The former studio chief oversaw production, sanctioned up to twenty days of cost and time overruns, and made sure Streisand was left alone creatively. Since Peters departed the studio, Streisand says, Columbia's support has remained "absolutely great—Peter Guber has made it 'Anything you want, Barbra.' "

SHE SHAPED THE SCRIPT with her customary fervor. "I had a very, very specific outline of this film in my head," she says. She moved Johnston into her Malibu house in May 1989 so she and the writer could toil daily on realizing that vision on paper. She was adamant from the beginning that she wanted flashbacks, which had not been a prominent feature in earlier script drafts. "I couldn't understand making this picture without that history," she says. "Why did the sister go nuts this time? And I wanted to pick those moments that had a profound effect on [Tom's] life. He was humiliated when his father roughed him up at the table and said, 'You're not going to cry; go put on one of your sister's dresses.' This is the story of all our lives, you know—we've all had those traumas. You become who you are from those moments in your life."

Two months before production, Streisand asked Conroy to polish the script with her. "I thought I was going to have to work with Count Dracula," he says. "And you know, we got along splendidly. I kept waiting for her to yell at me or something, hurt my feelings, but she never did. It was the best collaboration I've ever had. She's smart as hell." One of the perks of collaborating with Streisand was getting to camp out in her exquisite New York apartment. "When I was with Barbra, I lived like Louis Quatorze. She lives in the nicest places I've ever seen and eats the most wonderful food."

For Streisand, who virtually memorized the novel and during rehearsals frequently read passages to the cast, Conroy's input was a sweet bonus. "We just had a ball," she says. "What we did mainly was, like, exploring Tom Wingo. What a luxury this is—the author of the book! He was so cute, because I kept saying, 'Well, wait a minute: on page 338 . . .' 'cause he'd forget the book already." As a filmed homage to the author, "I put Nick in suspenders, because Pat wore them."

In Nolte, Streisand found a macho good ol' boy who would dive into his soul for her. "I thought Nick was the absolute right choice for the movie, in terms of combining the physical presence, his maleness, with the sensitivity and the coming to terms with the feeling and the pain. He was willing to go to those places that several actors that I know probably wouldn't let themselves go." She's not coy about how she would feel if he walked off with a golden statuette next March. "That would be wonderful. God, I would love that."

She lined up Jeroen Krabbe to play Lowenstein's violinist husband, Herbert Woodruff; Blythe Danner as Tom's wife, Sallie; Kate Nelligan as his mother, Lila Wingo; Brad Sullivan as his father, Henry; and Melinda Dillon as Savannah. Then she faced her trickiest casting decision. Streisand had auditioned an actor of Irish descent to play Lowenstein's son, Bernard, and was seriously considering casting him. Then Conroy, on a visit to her house, looked at a picture of her son, Jason Gould, on the piano. "That's Bernard," he said.

Streisand taped Jason reading the role and concluded that Conroy was right. "I was frightened to use my own son," she says. "What if they attack me for nepotism? But Pat said, 'I'm telling you, this is the kid. How do you use an actor that doesn't look Jewish? He looks like you, he is you.' And then Jason, who is not very ambitious and has never asked for anything in his life, really wanted to play it. And I thought, 'Screw all the possible negativity, I'm going to do what I think is ultimately right for the film.' " She was delighted with Jason's dogged preparation for the role, including three months of practice to play the violin convincingly in a key scene in Grand Central station. "My kid's a perfectionist, like me," she says. "If he didn't deliver, I'd fire him. I mean, I would fire him for his own good."

THROUGHOUT THE 85-DAY shoot, the director and crew had to stay nimble to constantly adapt to South Carolina weather and tidal changes. In New York, the challenges were different; Streisand found herself begging the manager of Grand Central station for another fifteen minutes of shooting time, and buttonholing strangers with "Hi, I'm Barbra Streisand. Do you mind being in the shot? Could you back your car up?" Early on, a family crisis put the movie in perspective. "Three weeks into it, my mother had to have a quadruple bypass. Once she was okay, it was like every day is such a gift."

Streisand aimed for emotional truth through simple rather than showy camerawork. "It's not like I have an opening shot like Scorsese's five-minute shot with a Steadicam. It didn't interest me on this picture." She fussed over every design element, however, devoting special care to Lowenstein's wood-paneled office, where seven scenes were filmed. "I don't know if people even notice things like this, but I will dye the silk of my blouse the exact color green as the chair that I sit on: I'm a detail freak. To me, performances are greater in black-and-white movies. I don't like the eye to look at too many colors. I like a monochromatic frame, where it's more like black and white."

In rehearsals, Streisand tried out several script variations, and she frequently filmed many interpretations of a scene so she'd have lots to play with in the editing room. "I'm like the queen of alternatives," she says.

From Nelligan's vantage point, Streisand "pays an incredible amount of attention to what is going on, and pleasing her is not real, real easy. Her standards of what it is to get it right are very high. She works harder than anyone I've ever seen in my life—there is nobody with her stamina, you see." Can she name one of Streisand's distinguishing traits as a director? Nelligan pauses. "Well, she just always wanted more."

Nolte won Nelligan's respect when he shot his first big scene. "Barbra did a lot of takes," she recalls, "and she'd stop and say, 'Now give me a little more of this or a little more of that,' and it went on, and Nick was on—I don't know how many takes, but it was up there—and at the end of each one, he would look up, and it would be 'What else can I do for you, what more can I give you?' He saw his function entirely in terms of how he could provide her with what she needed. It was really moving, both about him as an actor and also just as a man."

Wearing multiple hats affected Streisand's scheduling decisions. "If I were just an actress, I would have filmed my scenes first, when I felt fresh and not tired. But because I'm the producer and the director and I can save money, and also it's more convenient for the production, we made my office set a cover set. When it rained, we would have to move over, which would waste many hours, and film a scene in my office. Like where he teaches me to throw the football, that was done at 12 midnight, coming in from the rain."

"Barbra is never happier than when surrounded by twenty sweaty film technicians," reports cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt. "She loves it." She doesn't find directing herself a strain. "It's kind of fun to be all dressed up and sit on the camera and have these guys nuzzle me and smell my perfume and flirt with me when I'm setting up a shot. I find it kind of easy; I don't think of it as hard. I like that I can just jump into my role."

Columbia's Christmas wish was a Streisand-sung Prince of Tides theme song. "They would have paid me as much as I got to produce this movie," she says. For the soundtrack album she sang a version of "For All We Know," but she balked at including it in the film. "I didn't want to take the emphasis away from it being his story. I think to have a song at the end—it's like, 'It's his story, now what am I singing for?' I just didn't buy it. I know it would have been a nice marketing tool, and it could have gotten a Best Song nomination. But I said, 'I'm tired of singing for my supper. I always have to sing—why, you mean the movie isn't enough? I have to sing now, too?' "

IN THE FLASHBACK DINNER sequence, the Wingo family is gathered around the table: Henry, Lila, and three young actors playing Tom, Savannah, and brother Luke. The scene "is very significant, because it's about trying to get to the root of a man's problem; how our parents sort of inflicted this 'boys don't cry' rule to live by. In that culture and that time, that generation—who knows, it's probably prevalent today, too—the concept of 'I don't want a sissy for a son' really got me."

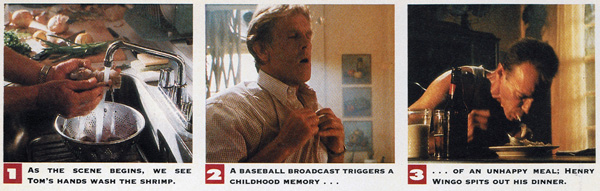

The scene opens as the adult Tom, a shrimper's son, stops at a Manhattan fish market to buy shrimp after a jog. Next we see him back in Savannah's apartment, washing the shrimp in the sink. Tom is hot, he's sweating, and there's a Yankees game on the radio. His father always had the ball game tuned in, and soon Tom is lost in reverie. We are tugged back in time by a voice-over of his father ranting about a shrimp Newburg dish Lila has just served the family, followed by a cut of him spitting it out. The rejected dinner is offered to the family dog, Joop, who won't touch it.

As Streisand intercuts four times between Nolte preparing the shrimp and the flashback, present time is represented in white daylight, while the past is differentiated by an orange, sunsetty glow. The sound interweaves the ball game, shrimp sizzling in the pan, and the dialogue of the Wingo family. "I just like the idea of following the human mind," says Streisand. "The human mind makes those cuts. Some sense memory happens, whether it's the smell of something, the color of something, the place."

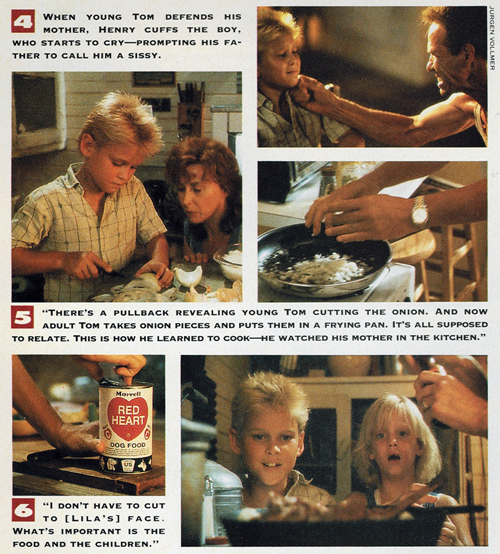

When it comes to children, says Streisand, "casting is 90 percent of the art," and she spent weeks combing the South for nine nonpros to portray Tom, Luke, and Savannah at three different ages. As Tom, towheaded Bobby Fain had the toughest moments, because Henry takes out his displeasure over the shrimp on him. Brad Sullivan improvised much of the father's scary raving. As Henry cuffed the boy in repeated takes. Fain at first held back the tears Streisand wanted to see. "[Sullivan] was a little rough on him, and what happened was the boy really started to cry, finally, because he was truly humiliated. After I got that take—it's the only one that I got— I held him for a long time, and I told him how wonderful that was."

In an attempt to restore peace to her warring tribe, Lila heads into the kitchen, followed by Tom and Savannah. We watch her fry up a new supper for her husband with a surprise ingredient—dog food—the camera cutting between Lila's and adult Tom's frying pans. "It's all supposed to relate. I mean, [Lila] just told him to melt the butter, so he's melting the butter in his [present] life."

Streisand shot the flashback cooking scene at the children's eye level, recording their delight at conspiring in their mother's joke. "I'm kind of dangerous, because I don't cover a lot of stuff," she says. "So there's no way I could have changed that—I only did it one way. I like to tell a story in one shot if I can, because why not? It's the simplest camera move, and yet you're getting the story. I'm interested in seeing Tom's face. We have to see the dog food emptied into the frying pan. And I don't feel like cutting away to anything else. That's the shot."

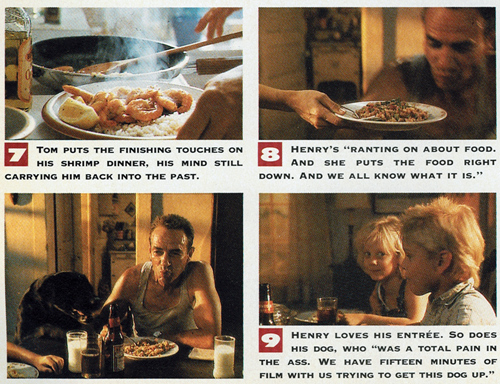

Lila comes out of the kitchen bearing her husband's canine hash. "He says, 'I want a good plain American meal,' and pounds his fist on the table. And she puts the food right down. He puts his fork in, and I carry the camera up to his face." With a mouthful and a great big grin, Henry declares, "Now, this is food, Lila." Joop, planting his front paws on the table, obviously agrees. Streisand closes her scene with a plain shot of a satisfied man and his dog.

Playing Joop, a black Labrador named Rocky delivered a bit of comic relief Streisand needed to wrap up the sequence, but at a price. "We hired this trainer to train the dog to walk away from the food and then to eat the food, right? There was no way this dog was going to eat this food. It was very funny. He was so untrained, this trained dog from South Carolina."

West Coast editor Nancy Griffin wrote about Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves for the June issue of PREMIERE.

END.

Related Link: “Prince of Tides” film pages

[ top of page ]