The Mirabella Interview

May 1998

Photo by Bart Bartholomew

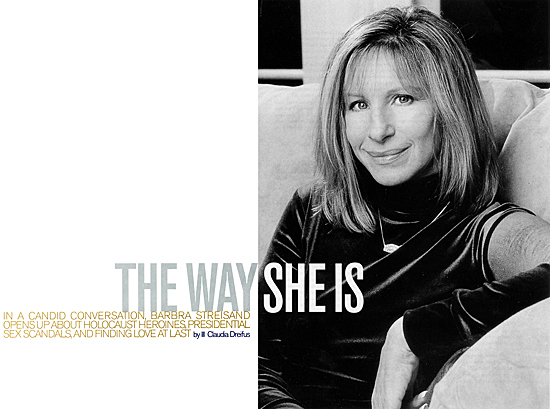

The very first thing Barbra Streisand wants to know when she greets this reporter in the living room of her Malibu home is “why the media hates me, why they insist on showing me as this bitch-diva?”

Actually, the Barbra Streisand I meet is most unbitchy, the opposite of a diva. Having agreed to a rare interview, she gives herself wholly to the process. Ask her a question, and she answers frankly, with the first thought that comes to mind. There are no taboos on subject matter, and no publicist sits in the room to protect her from a possible misstep. Most important, there are no time constraints put on the discussion. We fence with ideas for five hours. And then we talk some more later, on the telephone.

At fifty-six, the actress/singer/director seems to have reached a particularly happy moment in life. She's made a life-long commitment to actor James Brolin, who is crazy about her. There's a gorgeous white-diamond engagement ring on her left hand, and Streisand swears that she feels like she's “twenty-one and starting over again.”

In the public sphere—an area of life deeply important to Streisand—the star has discovered an effective new means for expressing her moral and political concerns. Her production company, Barwood Films, is producing teleplays on what she calls “social, historic, and political issues that would not otherwise be addressed in wider-viewed television movies.” None of these movies—and there are about a dozen on the drawing board—star Streisand herself. All of them are true stories that she feels need telling.

In 1995, Barwood produced the Emmy-winning Serving in Silence: The Margarethe Cammermeyer Story, on the plight of gays in the military. And on May 10, the second episode of Rescuers: Stories of Courage, a beautifully conceived, unsentimental set of dramas about Christian heroes in the Holocaust, will air on Showtime. As Streisand explains it, she is “drawn to stories where you do more than just help your own people. These people put the sacredness of life above differences in religious beliefs.”

Claudia Dreifus: You are someone who was born in the dying hours of World War Two. What did you know about the Holocaust growing up?

Barbra Streisand: Not much. Maybe that's something that drew me to this series, the desire to keep something so important from slipping from our historical awareness.

Did you have relatives who died in the Holocaust?

I don't know. My grandparents were born in Russia and in Austria, but my mother and father were born in America. They didn't tell me stories about the Holocaust.

I did the films because I'm interested in stories about man's humanity to man—as opposed to man's inhumanity to man. If you go to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, the most beautiful stories collected there are from people who say, “I shared my little piece of bread with another person to keep them alive.” This bonding, one human being connected to another, is so moving to me. My partner, Cis Corman, and I wanted to tell stories that reflected that feeling.

There are a lot of heroines in Rescuers. The women seem almost more heroic than the men.

Well, I'm always drawn to that—to promoting the strength and goodness of women. My production company is doing a lot of stories about courageous women. We did the Margarethe Cammermeyer story three years ago, we've got a movie coming up on May 3 about Congresswoman Carolyn McCarthy, who moved into politics after her husband was killed by a gunman on the Long Island Rail Road. We're doing a movie about Mary Schiavo, airline-safety crusader, and another movie about Ida Tarbell, the great muckraker.

But, not to leave men out, we're also doing a film about Yasir Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin, called Two Hands That Shook the World. These men grew up miles from each other, and yet they'd never met before their historic handshake at the White House. The script parallels the lives of these two leaders, from their childhoods to the point where they meet in Washington.

The Streisand Foundation gives money to support Arab-Jewish dialogue. What motivated you to start it?

I wanted to see my money do good during my lifetime. Not after I'm dead. I started giving it away, in a sense, before I could afford to, in the '80s, starting with a [cardiology] chair for my father at UCLA. I didn't have that much money then—big money. But it made me feel terrific, and I was glad to do it. Nowadays, the Streisand Foundation gives to social causes. For instance, we help fund a magazine, Common Quest, that's published by Howard University and the American Jewish Committee and that examines black-Jewish relations.

You are a strong supporter of President Clinton and a close friend of the Clinton family. How have you reacted to this Monica Lewinsky business?

I'm really pleased the American people are showing great support and good judgment in this matter. And the opinion polls show it. We can't let our country be turned into a police state where an inquiry is really an inquisition. I feel that it's no one's business what anyone does behind closed doors. What matters is how our elected officials perform their public duties—not how they function in their private lives.

Do you feel sympathy for Hillary Clinton in all this?

I feel a lot of sympathy for Hillary Clinton. But these matters, as I've said before, are none of our business.

But why do you think all of these scandals seem to surround the President?

I think the public knows the difference between Whitewater and Watergate and all these other "gates" they are trying to pin on this President.

I turned on the television a while ago, and [CNN's] Wolf Blitzer was saying something to Dan Quayle like, “The President's ratings are high, and the polls say that he's still on top.” And Dan Quayle answered something like, “Well, what do polls mean? What is important is what the American public thinks.” He's such a jerk. That's what a poll is. It tells you what the public thinks.

Scandals aside, many liberals who supported the President are disappointed in his policy decisions. Are you?

Not for the most part. We have a booming economy. He's done a lot of things I like. Like appointing Madeleine Albright Secretary of State. I mean, she's great—she's not afraid to be powerful. She's not afraid to call it like it is, you know? She's not afraid to say to somebody, “You're a liar.” A man wouldn't do this.

As for policy, the budget is balanced, we have the lowest unemployment in twenty-four years, family income is up, there is a $400 tax credit for twenty-five million families, violent crime is down four years in a row. He's accomplished a lot of wonderful things. Unfortunately, scandal is so prevalent, but he is a great President, and history will prove this.

So he hasn't disappointed you?

I didn't say that. Early in his first term, there was this thing with his old friend from college, Lani Guinier. I thought he should've stood behind her and fought for her. There were things he said that were naive— like answering questions about his underwear. But he's human— like the rest of us.

Let's switch gears to talk a little about cultural politics. How did you respond to the South Park depiction of you as Mecha-Streisand?

I wasn't even aware of this show until I read in Time magazine that they had used me in a very negative way. Let me say that I enjoy satire and parody and I loved the movie In & Out. It made me laugh. It wasn't mean-spirited. But I wonder if shows like South Park and Beavis and Butt-head don't add to the cynicism and negativity in our culture, especially in children. These youngsters are formulating their attitudes and maybe they come away feeling that any woman who dares to accomplish something is the incarnation of self-centeredness and greed. And that would be very unfortunate, especially for young girls.

You are often credited with changing the standard of beauty in this culture. Do you think that's true?

Perhaps, though there were a couple of sociological books that came out on beauty last year that didn't mention me, so maybe I didn't. When I started, in the '60s, the beauty symbols were young girls like Sandra Dee. Cute blonds, with little turned-up noses. And a lot of people, including my mother, didn't think I'd ever be a movie star. And it was quite a thing for me, all of a sudden, to have Cecil Beaton say he thought I was one of the most beautiful women in the world. It was great. I mean, he liked the bump in my nose.

Would you ever consider a face lift?

I would consider it. But I'm terrified of surgery. I don't have pierced ears because I'm so afraid. I mean, it's a big one, plastic surgery. All my friends have had it. They look great. I'm too scared still, too scared.

But it's your business to look good.

So I'll retire. I'm not all that ambitious anymore. Maybe I'll write a book. Set the record straight.

Set the record straight? What do you mean?

So many untrue things have been written about me that it just boggles the mind. A lot of it is character assassination, and if you're a celebrity there's just not much you can do about it.

I'll give you an example. There are half a dozen, perhaps more, biographies out on me. All of them are riddled with inaccuracies. One writer ... has Sheldon Harnick, the lyricist, quoting me as saying something like, “I wouldn't like it if God wrote my biography.” So my manager, Marty Erlichman, called Sheldon Harnick, who says he never said such a thing, nor has he heard me say such a thing.

So this gets written. It gets picked up and repeated in other books, and there's nothing much I can do about it. Celebrities can't sue because we're regarded as public officials, which we are not. We're not elected. You have to prove that the person deliberately wrote in error with malicious intent and knew, when he or she printed it, that the story was a lie. And how are you going to prove that?

But why care?

Because these kinds of things affect the ability of others to receive my work. Around that time, an article came out in People magazine with twenty-two out of twenty-five facts wrong. I was researching schizophrenia for my movie Nuts, I walked into Camarillo State Hospital to interview psychiatrists and patients, and someone said to me, “Are you as mean as they said?”

And then there are tabloids....

But you know as well as I do that the tabloids are the price we pay for the First Amendment.

This kind of cynical press is going to be responsible for a decline in American civilization. It's like the fall of the Roman Empire, this enormous emphasis on what's negative and trivial. I hold the media responsible to set certain standards. For instance, photographs that are published should somehow have some chain of responsibility. Something has to be done about hounding a celebrity for no good purpose. It's not in the public interest, even though it might interest the public. I've taken four walks near my house, and all four times my picture, surreptitiously taken, has appeared in the tabloids. Photographers hiding in cars and in bushes, scary!

You know, I kind of think freedom of the press ought to be about uncovering abuses and exposing tyrants, not about whether or not I'm walking down the beach in a junky sweater.

The paparazzo who takes the pictures is a kid who lives in the area. I wrote to his father. The father gives me plants because he's apologizing for his son. And I wrote him a letter last week, “Please honor my privacy. You know, I want to be able to walk on the beach; I want to be able to walk down the street ... without having to comb my hair.”

The first day I was in New York [for the Grammy's], I came out of my apartment to be chased by two photographers in a car. We lost them—but I thought of Princess Diana and how dangerous the instinct to flee is.

We haven't talked much about your new happiness in your private life. You met James Brolin in what has to be one of history's only successful blind dates. How did the relationship develop?

We saw each other a few times after that, but he had to go to Manila to do a movie. We had fabulous trans-Pacific phone conversations. He would call or fax me from Manila. We got to know a lot of details about each other's lives on the phone.

I was ready for love. I'd spent some time alone and was okay with it. I was at a stage when you're okay alone, when you appreciate yourself and your own solitude, when you're not accepting certain behaviors from men that you might put up with when you're younger. You'd just rather be alone. I think because I was willing to be alone, I found the right man.

What kinds of things did you put up with when you were younger?

Well, like a lot of women, I used to downplay myself for the sake of a man's ego. For instance, this house that I now have and that I really love, well, I looked at it a few years ago, when I was with someone else. He didn't like it—so I didn't buy it. But if something is meant to come back to you ... it does.

In times gone by, I've been with certain men where I didn't buy anything in the art world—paintings—just to make them not feel threatened by the fact that I could. I played myself down. Then, when you hit the time I'm talking about, becoming comfortable with yourself maturing and getting a little bit wiser, you're not afraid of becoming who you are.

Did you ever think that you'd reach that point?

No. I thought that I was given enough, I was privileged enough, and I was blessed enough. I was given, you know, my health, my career, my son, devoted friends—people in my life for many, many years. I thought probably it was too much to ask, you know, for real love, too.

Before you met James Brolin, weren't you dating Peter Jennings?

Dating? I saw him a couple of times. Once I was going to take [former Canadian Prime Minister] Pierre Trudeau to a White House dinner, but he was out of the country. And so somebody said to me, “Peter Jennings wants to meet you.” I said, “Yeah? Maybe I'll ask him if he wants to go to the White House with me.” And he did. It was a fluky, funny thing.

Around this time, I was putting the finishing touches on a speech I was to give at Harvard that I'd been preparing for more than three months—talking to theologians, historians, political people. So one evening, Jennings was in California giving his own speech on education in Bakersfield, and we went to dinner, and he asked to look at my speech and was very critical of it. He was saying, “Oh, Jesus, I wouldn't say this and I wouldn't say that.” He just made me feel really awful and I didn't want to discuss it with him anymore.

Not long afterward, an item appears in Liz Smith's column suggesting we'd been groping each other across the table at this dinner. Totally made up! So he gets annoyed and he writes her, saying something like, “The only thing that we were handing across the table was the speech Barbra was writing.” And I called him and said, “Peter, do you know what you just did to me? You just associated yourself with my speech.” He says, “Barbra, don't be silly.”

So of course a few days later, it's in the gossip column in in The New York Post, how Jennings helped me with my speech. I called him and said, “Please have your press person call [New York Post Page Six columnist] Richard Johnson and say that's an absolute lie.” And he says, “Oh, Barbra, forget it, what does it mean?” I said, “You write a letter to Liz Smith saying we weren't groping each other across the table. You can tell them you didn't help me my speech, because you didn't.” He wouldn't do it. I've never talked to him since.

After all the untrue things written about you, what would you like people to know?

That I always tell the truth!

End.

[ top of page ]