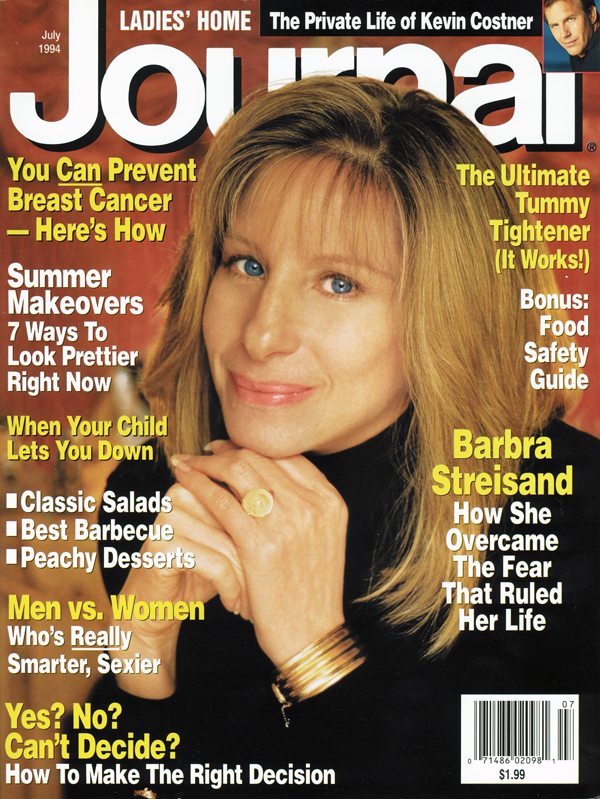

Ladies’ Home Journal

July 1994

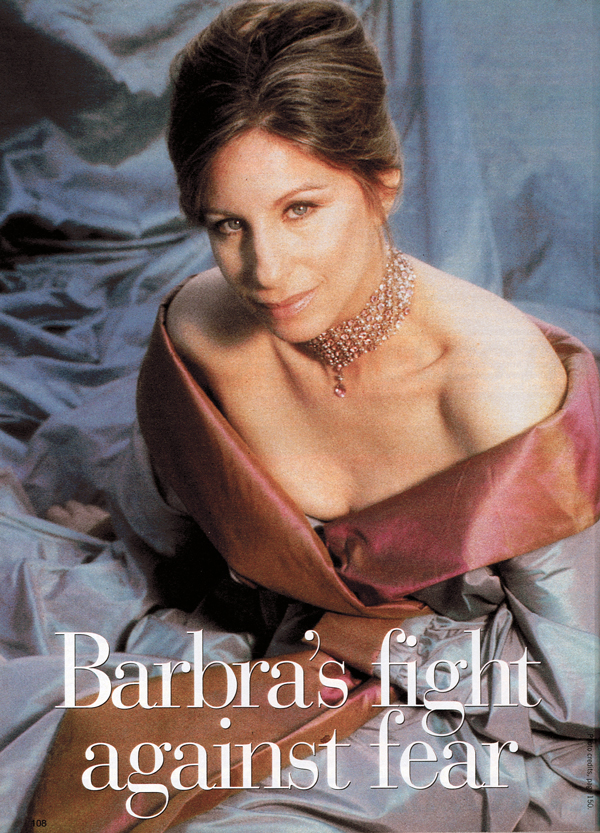

She's a legendary singer—yet, for years, a phobia held her back from doing all she was capable of. How did she overcome her most terrifying obstacle?

by Susan Price

Cover Photo: Terry O'Neill

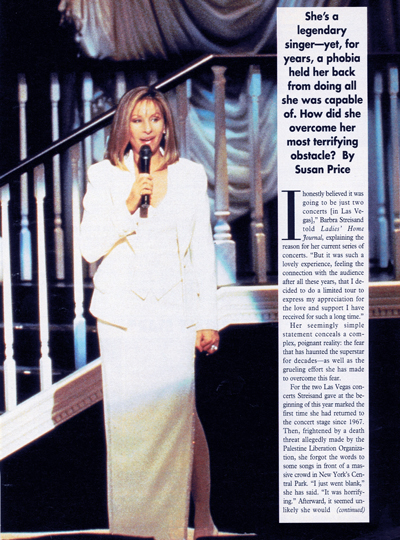

“I honestly believed it was going to be just two concerts [in Las Vegas],” Barbra Streisand told Ladies' Home Journal, explaining the reason for her current series of concerts. “But it was such a lovely experience, feeling the connection with the audience after all these years, that I decided to do a limited tour to express my appreciation for the love and support I have received for such a long time.”

Her seemingly simple statement conceals a complex, poignant reality: the fear that has haunted the superstar for decades—as well as the grueling effort she has made to overcome this fear.

For the two Las Vegas concerts Streisand gave at the beginning of this year marked the first time she had returned to the concert stage since 1967. Then, frightened by a death threat allegedly made by the Palestine Liberation Organization, she forgot the words to some songs in front of a massive crowd in New York's Central Park. “I just went blank,” she has said. “It was horrifying.” Afterward, it seemed unlikely she would ever perform in public again.

“You don't get over stage fright—you just don't perform,” she said. “I don't think I can do it again.”

Yet she has done it, in a big way, beginning with London's Wembley Stadium in April, through Washington, D.C., in May and ending in late June with five performances at New York's Madison Square Garden. Each appearance sold out within hours, and the tour is expected to net millions of dollars.

And that's not all. Over the past several months, Streisand has been doing a lot more than conquering the fear that has limited and dominated her life. She has disposed of her Malibu estate, sold her treasured Art Deco and Art Nouveau collection for $5.8 million (“The selling of my collectibles,” she's said, “is a cleansing of my heart, my mind and my soul”) and is planning a number of controversial film projects. What's more, she has never looked better; her famously translucent skin is as clear as ever and virtually wrinkle-free (Manhattan dermatologist Dr. Pat Wexler has reportedly done some wrinkle-plumping work on her); her body is toned and firm. At the age of fifty-two, Streisand appears to be beginning a new phase of her life.

THE ROOTS OF CHANGE

Why is she able to put her fears behind her now, to do what she once thought was impossible? There is no simple answer; instead, a number of factors have combined to make the change possible.

Part of Streisand's renewed interest in performing, entertainment-industry insiders say, may be due simply to her $60 million contract with Sony, which includes $2 million a year for ten years to develop projects; $3 million for a movie she directs; a $4 million advance for every movie in which she stars; and a $5 million advance for each of six albums she is expected to produce. High-priced projects like these are unquestionably helped by a star's high visibility.

And the fear of growing old and outdated may also be part of her return to the stage. “She might be going out there again because she really feels that she's become a memory, a legend in her own time, and she wants to be real again,” says Stuart Fischoff, Ph.D., media psychology professor at California State University, Los Angeles. “She wants to have some contemporary meaning.”

But that isn't the whole story. Streisand's newfound confidence is also due to a long, intense self-examination that includes years of therapy as well as encounters with New Age-style spirituality.

And perhaps the most important factor, the singer's friends say, is pure old-fashioned stubbornness, the kind of stubbornness that made a poor girl from Brooklyn, New York, determined to transform herself into a superstar.

“I think there's a tenacity that she's probably had since the time she was a little girl—to always want to be better and always ask more of herself,” says lyricist Marilyn Bergman, who, with her husband, Alan, wrote the lyrics to one of Streisand's signature songs, “The Way We Were.”

“This [returning to live performance is overcoming fear. And I think that because she was so afraid of it, it made her want to feel that she could conquer it.”

But if Streisand is no longer paralyzed by fear, she's still very anxious about appearing onstage. Mindful of the long-ago death threat before the Central Park performance, she has imposed antiterrorist-level security measures at her concerts, with every member of the audience required to go through an airport-style metal detector.

A PERFECT STAR?

Fear isn’t the only thing that’s kept her from performing, though. She was also, friends say, reluctant to be involved in any project over which she had less than total control. “When you’re doing it live,” explains one friend, “you simply do not have that control.”

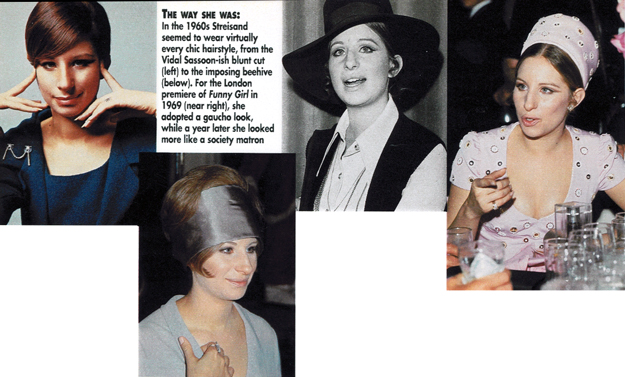

And for Streisand, control is key—whether onstage or off. To say that she wants—and gets—her own way is a laughable understatement. She is legendary among journalists for insisting on approval of everything from photographs to quotes. She doesn’t allow anyone to photograph the right side of her face, which she says is too masculine-looking. When she appeared in London, she had the entire floor area of Wembley Stadium—the equivalent of, say, Yankee Stadium or Candlestick Park—covered in blue carpet. Why? Depending on whom you believe, she either liked the way it looked or thought it would provide better acoustics.

Streisand is defensive about being a control freak: “You don’t ask a man, ‘Do you want to be in control?’—you assume he wants control,” she’s said; “Why would a woman be any different? . . . How could anyone not want to be in control of their work?”

Her associates say, tactfully, that she simply never wants to give less than her best. “Why shouldn’t she be involved in every decision?” one friend says heatedly. “When that red light goes on, or the conductor gives the downbeat, she is the person who’s standing there alone. The stage is pretty naked; it’s a very vulnerable place to be.”

But it can also be a wonderful place when, like Streisand, a performer craves—and gets—frenzied adulation from thousands of fans, the people who provide instant, loving feedback.

Of course, as anyone familiar with Streisand’s story knows, love is exactly what she missed as a child, and what she appears to be in constant search of. “If you don’t feel loved as a child,” she has said, “you spend your life trying to get that love.” Her father, Emanuel, an English teacher, died when she was fifteen months old. Several years later, her mother, Diana, married a used-car dealer, Lou Kind, who, Streisand has said, never spoke to her except once, when he told her to be more like one of her friends—quiet.

Streisand has also had an unhappy, complicated relationship with her mother, who she has said did not give her enough emotional support: Diana Kind urged her daughter to forget singing and get a clerical job. And when she first saw Streisand act, the singer recalled, Mrs. Kind had only one comment to make: “Your arms are too skinny.”

Streisand has tried to forgive her mother: “I saw she did the best she could, you know?” she has said. “It’s just another generation. And she obviously caused me to be who I am today. Because I was only trying to prove to my mother that I was something.”

But some ambivalence remains, and her mixed feelings are obvious even in concert. During one of her Las Vegas appearances, she asked her mother to stand for applause from the audience, and then, with a trace of impatience, abruptly told her to sit down.

It may be that those unhappy early relationships have left Streisand unable to have a long-lasting relationship of her own. “I live with a lot of angst,” she has said. “I’m a mass of contradictions. I change and I grow. I change my mind all the time. So tell [whatever] man I’m looking for that if he likes to have affairs with lots of women, then I’m perfect for him!”

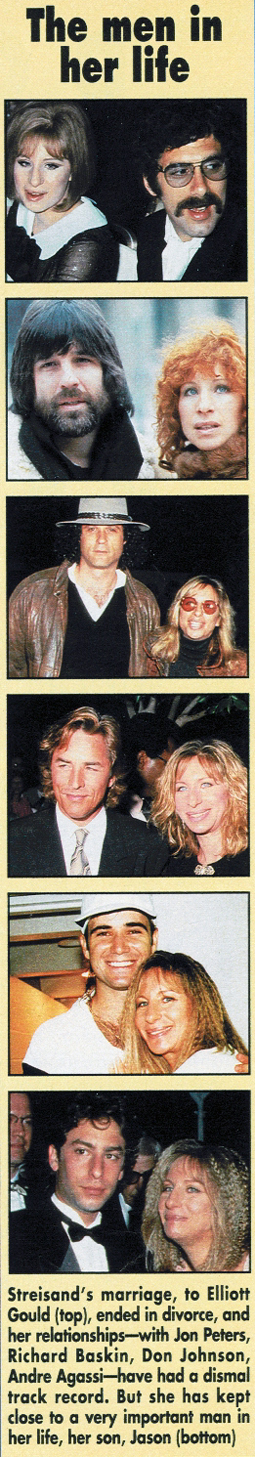

Streisand hasn’t found that man, despite a string of relationships with, among others, Elliott Gould (her only husband and the father of her son, Jason, now twenty-seven), Ryan O’Neal, ice-cream heir Richard Baskin, producer Jon Peters, Don Johnson, tennis player Andre Agassi and Pierre Trudeau, the former Canadian Prime Minister with whom she’s recently been seen again.

“ [People] were meant to be together with somebody,” she has said. “We’re meant to have a mate.” (That sweet wistfulness, so rarely seen in public, so appealing to men in private, has enabled her to remain friends with most of her ex-lovers.)

The superstar’s anxieties about men form a small but significant part of her concert patter, in which she tells an off- stage “analyst” of her uncertainties about who opens the car door or picks up the dinner check—questions that, if they are genuine, are surprisingly old-fashioned for one of Hollywood’s most powerful women. Undoubtedly, Streisand does have a vulnerable side: “I’m supposed to be this big, powerful woman, but I’d be scared to get on a train by myself or travel alone through Europe. So there’s always a contradiction.” '

BARBRA'S NEW AGE

She’s tried to explore the particular contradictions in her life through therapy—beginning more than thirty years ago: “I always thought I’d adjust well to success. Clearly I didn’t. The first week Funny Girl opened I was on the covers of Time and Life. It was too much for me. It put me into analysis.”

Besides that grueling, often painful process of self-examination, Streisand has explored a number of other paths as well: She’s expressed interest in the ideas of poet Robert Bly, inner-child theorist John Bradshaw and mythographer Joseph Campbell, and she’s reportedly held a few at-home spiritual gatherings for her friends.

She’s also gone recently to a retreat center in Arizona run by a guru-type figure called Brugh Joy. There, associates report, Streisand has joined in “group work” that involves aerobics, yoga, meditation and interpretation of dreams. In fact, though Shirley MacLaine has a reputation for being the spaciest Hollywood star, MacLaine, a friend of Streisand, has said, “Barbra rivals me in questioning values and human behavior.”

Yet, for someone who professes such a high degree of spirituality, Streisand can be both inconsiderate and rude. Associates recount her screaming fits on the telephone with humorous awe, and even some of her most ardent fans were embarrassed in Las Vegas by her lengthy onstage trashing of the hotel/casino where she was performing. Streisand’s chief complaint: There were no soap holders in the bathroom. “They were paying her millions of dollars,” one fan said bemusedly. “Couldn’t she have bought her own soap dish?”

THE CLINTON CONNECTION

But the superstar has a charitable side as well. The organization she founded, the Streisand Foundation, has given more than $7.5 million to environmental, civil-rights and AIDS research groups. She herself made substantial donations to local groups following the Exxon Valdez disaster and the Los Angeles riots. And she has spoken out on controversial political issues such as the anti-gay-rights amendment passed by Colorado voters in 1992.

It is Streisand’s involvement with the Clinton White House, however, that has drawn the most attention. She has spent the night in the White House, dined with Attorney General Janet Reno and attended Congressional hearings on gays in the military. Nonetheless, she angrily blasts as “a joke” the charge that she is trying to be a political force.

Gossip says that she and the President have a mutual crush on each other and that Mrs. Clinton may be somewhat less enamored of Barbra. That seems unlikely, associates say. What is true, however, is that both Clintons admire her talent and professionalism—not to mention the money she can raise. And she is attracted to the President’s power, education and politics.

She also developed a close relationship with his mother, Virginia Kelley, who died early this year of breast cancer; Streisand donated $200,000 to a breast-cancer fund in her memory.

The star’s interest in political and controversial causes extends, these days, even to her work. She is planning to direct a film version of The Normal Heart, a play by gay activist Larry Kramer about the early days of the AIDS epidemic and, Streisand says emphatically, “everybody’s right to love.” She has also optioned the story of Colonel Margarethe Cammermeyer, a National Guard officer forced to resign from the organization because of her lesbianism. Significantly, her third big project has personal rather than political meaning—she plans to star in The Mirror Has Two Faces, the story of the difficult relationship between mothers and daughters.

But amid all these high-powered projects, Streisand’s most meaningful triumph may just have been one moment last January, when on a Las Vegas stage, in front of an audience that included everyone from Michael Jackson to Gregory Peck, the unthinkable happened: She made a mistake. A fairly small one, as mistakes go, but a mistake nonetheless: She flubbed a few words to Evergreen, the 1976 Academy Award-winning hit she co-wrote with Paul Williams. But rather than stopping, or letting her embarrassment mar her performance, she simply smiled and said lightly, “And that’s one of mine,” and kept right on singing.

The audience rewarded her with even wilder applause than they’d been giving her as she sang the introductory notes to each familiar number. Said one adoring fan, “It just made me love her more to know that she allowed herself to be so vulnerable with us.”

Streisand swept triumphantly through the rest of her performance that night, joyously telling her audience, “I did it! I did it! I did it!”

No one who saw her that night doubts that she’ll keep on doing it.

END.

Related: Barbra's 1994 Concert Page