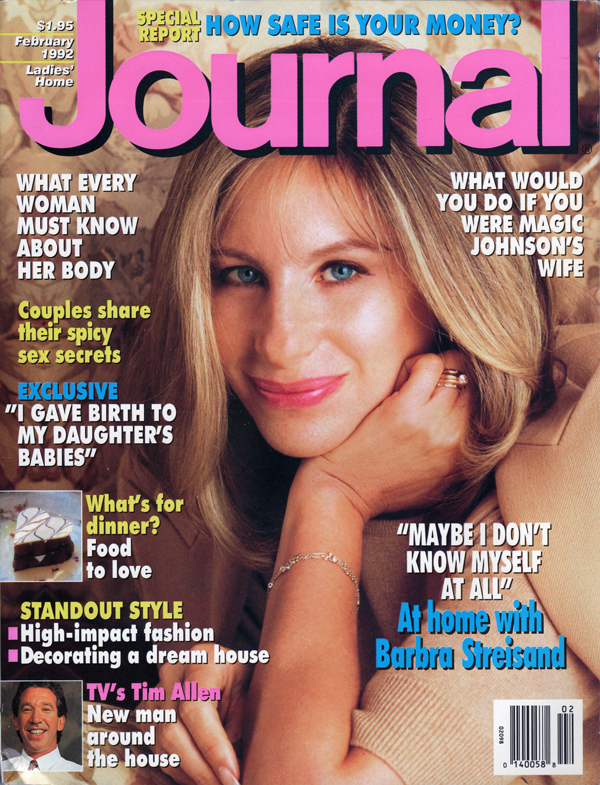

Ladies Home Journal

February 1992

When you first walk into Barbra Streisand's large but cozy apartment on Central Park West, in New York, you wonder whether you're in the right place. How could Streisand—the most assertive woman in Hollywood, the producer/director/star of The Prince of Tides, feminist and defender of every difficult cause—surround herself with all these doilies and pink frills? And isn't she supposed to be as reclusive as she is powerful? Then what are all these happy laughing photos doing everywhere, showing Barbra and her friends enjoying themselves while skiing, playing tennis and shopping for antiques?

Just down the hall from the candy-box living room, there's an office that looks more like the Streisand we think we know: sleek and no-nonsense. How can the same woman occupy both? Because Barbra Streisand not only acknowledges her contradictions but revels in them. "I'm scared AND I'm strong," says Barbra in a rare extended interview. "Now, I'm supposed to be this big, powerful woman, but I'd be scared to get on a train by myself, or travel alone through Europe. So there's always a contradiction. Like I have periods where I'm very centered and lucid and loving. And then I go through periods where I feel just absolutely dysfunctional."

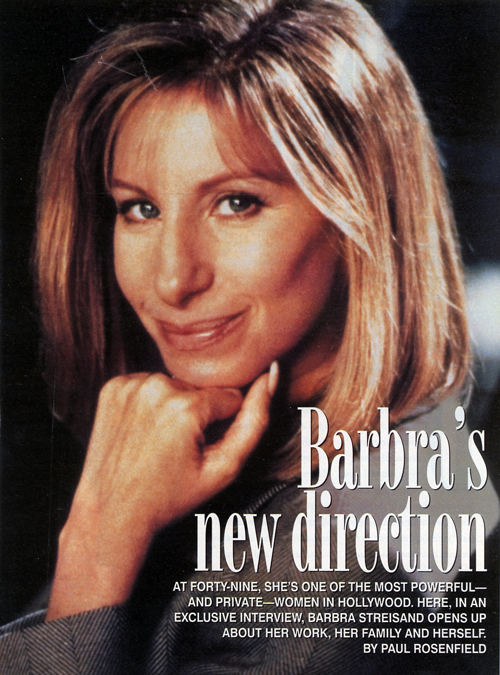

Not these days, however. Dressed in an elegant black wool pantsuit, her hair blond and straight, Streisand, who'll turn fifty in April, looks radiant. She's never been busier. Her thirty-year, four-CD retrospective, Just For the Record—packaged in a pink, froufrou box that resembles her living-room decor—has been riding the pop charts since October. And late in December, The Prince of Tides, her first new film since Yentl, in 1983, opened to great fanfare. Adapted from Pat Conroy's novel, the movie concerns a disillusioned, troubled high school football coach, played by Nick Nolte, who leaves his home in rural South Carolina to help his suicidal sister, a writer in New York. He falls passionately in love with her psychiatrist, depicted by Streisand in a very romantic role.

Love has played a big part in almost all of Streisand's movies; she has been paired with leading men from Robert Redford to Kris Kristofferson—but rarely with happy endings. "Too many of my heroines don't get the man," she says, with a smile. "That's one of the reasons why I wanted to do [the Michelle Pfeiffer role in] Frankie and Johnny," she adds. "I wanted to do a movie where I get the guy."

Although that movie slipped through her fingers, she hasn't given up the notion of producing a sequel to her 1973 smash, The Way We Were. This time, she promises, she and Robert Redford would be together in the fade-out. "That movie would be about how passion wins over intellect. In The Way We Were, it doesn't: Passion gets relegated to second position. But there's no question, he is the love of her life."

As for her own romantic life, Streisand is less forthcoming. Does the one-time wife of actor Elliott Gould—who has dated everyone from stars Don Johnson, Warren Beatty and Ryan O'Neal, to hair- dresser-turned-movie-mogul Jon Peters, and most recently, composer James Newton Howard—still believe in love? "I know couples in my life who adore each other, and they're together. That's the way it's supposed to be. It takes very special people. Most people are too screwed up somehow. So many people are afraid to love that much. They're frightened of a sense of loss ... We were meant to be together with somebody," she says finally. "We're meant to have a mate."

But contrary to assorted tabloid reports, she says, she won't be reuniting with ex-husband Gould. "[The tabloids say] I'm back with Elliott because we went and had a bagel. It's so bizarre to me ... And I hate it—I don't want to know about it."

Still, it's hard to ignore the scandal sheets, especially recently when one ran a story alleging that Barbra's son, twenty- four-year-old Jason Gould (he plays her estranged son in Tides), went through a marriage ceremony with a male model. Barbra, who terms the tale utterly false, was outraged by it—and still is.

The slings and arrows of celebrity do seem to sting Streisand unusually sharply, considering how long she's been a star. She complains about the tour buses that stop near her Beverly Hills estate: "I mean they literally come like, say, every three minutes."

Nor has Streisand ever gotten used to her portrayal as an obsessive control freak. "You don't ask a man do you want to be in control—you assume he wants control," she declares. "Why would a woman be any different?" She still smarts over stories that Steven Spielberg was her mentor on Yentl; in truth, she says, his only advice after seeing the finished version was "don't change a frame."

Sipping Japanese miso bean soup, she warms to her subject. "People see it as some ego trip, it's the weirdest thing. What does producing mean? It means getting it on the screen, watching over it like it's my baby. What's wrong with a woman doing that? How could anyone not want to be in control of their work? It's a very antifeminist thing we're talking about here."

Streisand thinks females are often antifeminists themselves. "Women are so competitive with each other. It's just horrible! Women are not supportive of each other in general. Look at the women who called in about Anita Hill. The number who thought she was lying shocked me. She was the smartest, she was the best looking. She probably had the most style, the most grace, the most opinions. And they're ready to go in there and crucify her. This was a witch hunt. They were going to burn her at the stake. Somehow, it was like she was accusing their husbands or their fathers or their sons."

Why does she think some women are so resentful? "Maybe it's because women are not taking their own power," says the founder of the Streisand Foundation, a nonprofit group that has given almost $4 million to liberal educational, political and environmental causes in the last few years. "They're not doing more to help themselves. So they are angry. So they have to denigrate another woman as an equalizer. I used to say that about Judy Garland, because she would try to commit suicide every once in a while—that was the equalizer in her life. So people could pity her and not hate her." Barbra, who once sang duets with Garland, recalls how Judy's hands shook. As for herself, Streisand says, "Women at first don't know whether they should trust me"—although she's proud to count several women among her best friends, including lyricist Marilyn Bergman, producer Cis Corman and Shirley MacLaine.

Streisand concedes she's not very easy to get close to, despite years of psychotherapy. "I once went to this therapist, and I said, you know, one of my problems is that I don't trust people. And he said, 'Why should you?' He said trust has to be earned. And I said thank you. I didn't feel so bad about myself."

Barbra readily admits to being iron-willed. "I think nothing is impossible. I think you can be whatever you want to be. And I believe that. I don't accept the word no easily. I've always been fighting it my whole life ... You can't sing that, you can't do that, you can't wear that, you can't have that nose. You know, all that stuff. I've always heard no. I can't stand it."

Making this new movie has softened some attitudes, though, and now Barbra is heading in a new direction. Much of the Tides plot concerns family love, loss and forgiveness, and she's trying to learn to deal with those feelings for real. Her father died when she was fifteen months old, and she grew up in pinched circumstances with a critical and distant mother.

It took a while, she says, but now she can understand her past. "When you start to have compassion for your parents or for people who have hurt you, and then subsequently forgiveness, you also realize that sometimes there's nothing to forgive." As for her demanding mother, "I saw she did the best she could, you know? It's just another generation. And she obviously caused me to be who I am today. Because I was only trying to prove to my mother that I was something. That I could make it."

Yet there is sadness. "I know if I had a father I would be a happier woman," says Barbra wistfully. "I would probably be married-happily-and have two or three children."

What does she know on the brink of fifty that she didn't know at twenty-five? "I am beginning to accept myself," she says softly. She thinks it shows. "It is interesting how I've gotten better looking. I like my face now more than when I was very young. I think I grew into my face."

And herself. "I am very shy, and when I came to Hollywood in 1967, I was intimidated by the movie stars." What she didn't realize was that she was already one of them, having stormed Broadway and London with Funny Girl, not to mention her string of hit record albums. She was just twenty-five years old. Her Funny Girl producer, Ray Stark, "gave me this big party when I got to Hollywood. It was like I couldn't believe it. Here I am meeting Cary Grant! Or Marlon Brando, the only actor I ever really idolized. These people were at a party for me? The next day I read in the columns that I was arrogant and aloof. The truth is, I was absolutely frozen to my seat."

But didn't she always think she'd be a star? "All right, I wanted to be a star when I was a child. I'm ambitious, but I was never ruthlessly ambitious," she insists. "I always had too much pride to knock on peoples doors and say, 'Give me a job.' I would have given up the career if I had not gotten the job in [her first Broadway show I Can Get It For You Wholesale.

"I would have become a hat designer. What I don't like is the stereotype of the Jewish aggressive woman. That's not who I was, or who I am."

She pauses but doesn't let go. "It's like when they use the word chutzpah about me in reviews. Even that, I think, is based a lot on Fanny Brice [the legendary Brooklyn-born singer, comedian and Ziegfeld Follies star who inspired Funny Girl. And I'm not Fanny Brice."

Then Barbra Streisand, the queen of contradictions, does exactly what you expect her to do—she reconsiders what she just said.

"On the other hand, maybe I do have chutzpah," she says quietly. "Maybe I don't know myself at all."

End.

[ top of page ]