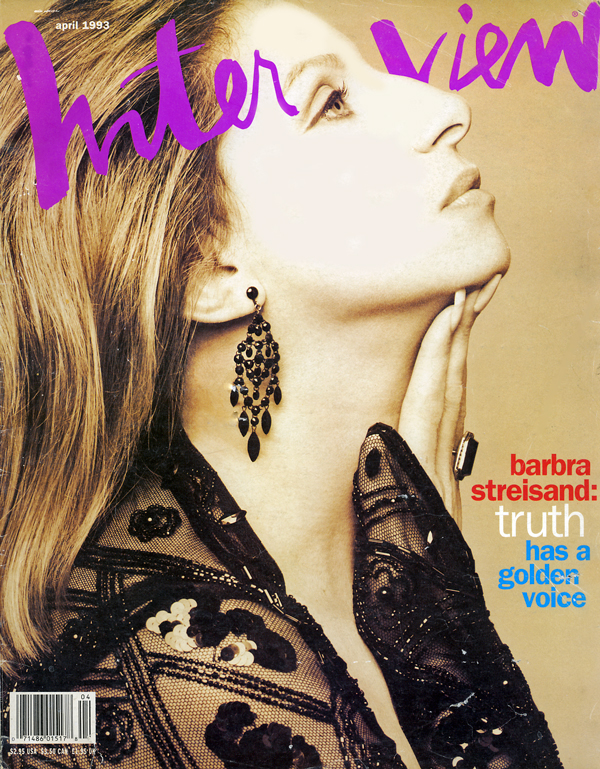

Interview

April 1993

Cover photograph by Herb Ritts, 1991

America's First Voice

Someone asks you about Barbra Streisand. Maybe you think about the way you were when you first saw her, or heard her, any number of years ago.

When I was asked recently about Barbra Streisand, I thought about a certain luncheon last fall at Le Cirque, in New York City, with then First Lady Barbara Bush before the presidential election. Many editors were there— I was among them as a reporter—and after a while we were encouraged to ask questions of Mrs. Bush. It was time for dessert—small cakes baked to replicate the American flag, unfurling in fits of spun sugar—when I nervously raised my hand.

"Yes, sir," Mrs. Bush said.

"One aspect of the Republican campaign seems to be an all-bets-are-off willingness to delegate women, intellectual Jews, and gay people to a category of Other," said I, "and as two of those—"

"Which two are you?" Mrs. Bush interrupted, prompting a great deal of nervous laughter.

"All three, ma'am, on a Saturday night," I said.

And it went like that, between me and Mrs. Bush, who adamantly disagreed with my assessment of the Republican campaign. "I'm for ya," she said, "and so is George Bush. And I don't like that impression of the Republican Party at all."

We disagreed more. Across the room at Le Cirque I saw heads atop executive-gray suits shake, and in the shaking went a certain job I might have liked, but the good news was that I had found my voice. And that my voice had found me. I had spoken. The exchange was widely reported in the press, this idea that the messenger had become the message.

I remembered all this when I was asked to think about Barbra Streisand. It wasn't her so-called diva thing I thought about. I thought about Streisand's voice, but not just the extraordinary voice of popular songs that make us laugh and cry and look for love lost in all the right, and wrong, places. I thought about all the passion and commitment she has voiced of late about the environment, about AIDS, women's rights, Anita Hill and sexual harassment, gay rights, the boycott of Colorado, as well as all she said and did to bring about a change of guard of our elected leaders in American government, bringing with that a very different kind of First Lady from Barbara Bush.

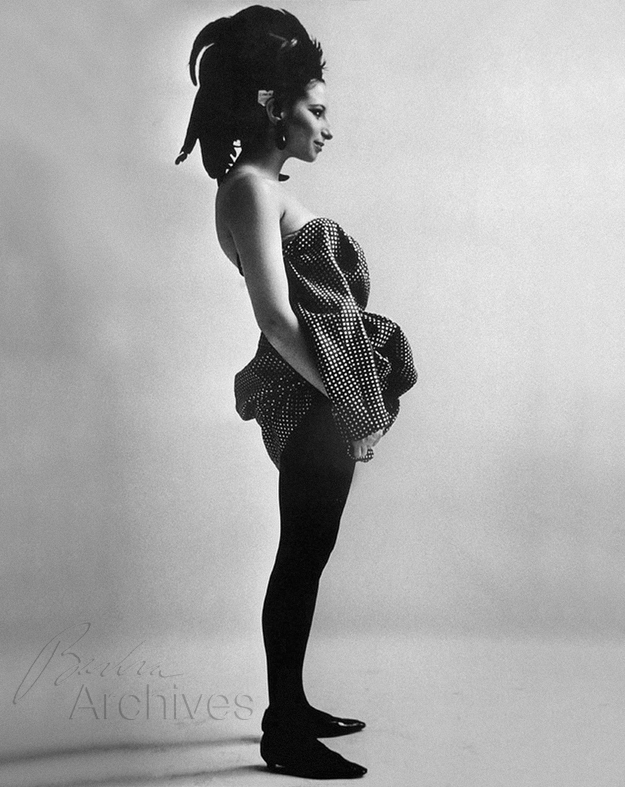

Photograph, above, by William Claxton, 1964

In Barbra Streisand, America has its first voice, a voice that Quincy Jones once described as "a Stradivarius." Her ultimate song is that she has been using her voice in a manner that becomes a record of permission, hers and ours.

I remember getting to stay up late when I was young to watch a television show called My Name Is Barbra, and there was this extraordinary-looking creature almost levitating through Bergdorf Goodman in a town we would all have to run away to someday. New York City. When it came to New York City, as a child I always kept a brown bag packed with clean clothes under my bed for any sudden departure to it and all it had to offer. When I was older, I found out in the city you were free to be, and all was right in the world for people who need people, especially the people who, at first glance, didn't seem to fit, in the scheme of things. Even if no one else wanted you, the city wanted you if you would work hard-having run away to the city, like Streisand, even if you had to sleep on a cot you carried from friend's apartment to friend's apartment, your blessed salad days-and all the hard work engendered good karma. Obviously, Barbra Streisand got there before me, long before everyone was famous for fifteen minutes.

It is recorded that Barbra Streisand's mother told her she wasn't pretty enough to act and that her voice was too weak for a singer's, and she advised her daughter to become a secretary. So Barbra Streisand grew her nails. Who could be asked to type then? Barbra Streisand turned out to be the exemplar of unexpected talent and unlikely-beauty.

And she is funny and frank. During one of her earliest auditions in the city she "forgot I had gum in my mouth, and I took it out and stuck it on the microphone. It got a big howl."

There are few soldiers who go against the norm the way Streisand does. As she became more beautiful to us, the world went ugly. After a reported PLO threat against her life during her famous Central Park concert in 1967, she froze, never to perform in public again until 1986. "I could never imagine myself wanting to sing in public again," she said in tape-recorded invitations to a Democratic fundraiser she would host that September at her house in Malibu, "but then, I could never imagine with all our advanced technology the starvation of bodies and minds and the possibility of nuclear winters in our lives—I could no longer remain silent; by my silence I was giving consent to the madness of nations spending billions of dollars on weapons that can never be used—and all at the expense of our schools, our farms, medical research, and research into safe sources of energy. Sometimes we forget the importance of one voice, of each of our voices, and the enormous difference it can make in all our lives—in history. I feel I must sing again to do what I can to ensure a safer and better world."

Barbra Streisand fights the good fights. She fights Hollywood's established bias against women, the bias in which she is considered pushy for working as a perfectionist, or as a director as well as an actor, when any man is called a creative genius for doing exactly the same thing. Streisand fights for rights such as those denied by Colorado's approval of its Amendment 2, which mandated no protected status based on homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual orientation. "If that law were passed against Jews or people of color, the whole country would be outraged and nobody would question a boycott of that state," said Streisand.

Most recently, Streisand worked hard to get Bill Clinton elected as President and other politicians as members of Congress. About this she said: "We didn't do so in order to be invited to formal state dinners at the White House. We supported these candidates because they promised us profound change. And we want them to know—we will be listening, watching, and waiting."

The Hollywood establishment, and that includes the Hollywood press, tends to criticize its stars when they speak out. In the old days, stars kept their mouths shut. In those old studio days one hoped for hidden messages beyond the facades of glamour and allure. Now, through supermarket tabloids and electronic media, we know every single detail of a star's life. Notions of private lives made moot, why shouldn't they speak out? And now we know it is the Voice that gets the message out. Streisand, America's first voice, proves this to be true over and over. How about what she said regarding one of her colleagues: "I will never forgive my fellow actor Ronald Reagan for the genocidal denial of [AIDS's] existence, for his refusal to even utter the word 'AIDS' for seven years, and for blocking adequate funding for research and education, which could have saved hundreds of thousands of lives."

When the New York Post reported Streisand might seek elected office, in a story headlined SENATOR YENTL, she responded by saying she was a filmmaker, that making a movie of Larry Kramer's historic play about the beginnings of the AIDS epidemic, The Normal Heart, would do more good than if she were elected to public office. The message we hear? Action comes in lots of ways. From her voice. Your voice. Our voices.

BY WILLIAM NORWICH

End.

[ top of page ]