Pat Conroy on the Making of 'The Prince of Tides'

US Magazine

January 1992

Just weeks before the film adaptation of his book ‘The Prince of Tides’ hit the screens, Pat Conroy sat down with senior writer Holly Millea in a Manhattan restaurant to discuss his experiences working with Barbra Streisand on his first screenplay.

I DON’T KNOW how Barbra got the rights to The Prince of Tides. But I’m sure fate played some part in it. I listen to music when I write. And Barbra was the performer I listened to while writing The Prince of Tides. To go from that to working with her was incredible.

Let me start from the beginning. You see, I had written the screenplay adaptation of my book back in 1986. Then I had a fight with the producers, in which I told them to take the script and shove it up their behinds. I never talked to them after that. I heard by rumor that Robert Redford owned the rights to it for a while [he and Streisand discussed doing it together]. I didn’t know he had given it to Barbra. So when I started receiving messages to call Barbra Streisand, I thought it was a joke. I have a friend from high school who used to leave me these kind of false messages all the time. I remember one time he left a message saying, “Call President Carter. He saw The Great Santini [based on the book Conroy wrote in 1976] and he wants to talk to you about it.” So I call the White House and Carter had never heard of me. So l thought this was just my friend playing a joke.

Finally, I was at a hotel in Los Angeles one day and Barbra said, “Why won’t you return my phone calls?” It was horrible. I felt like the rudest person in the world.

We worked together on the script for two weeks. And she worked me those two weeks, I do want to tell you that. She would give me homework — five or six scenes to look at a night. I was afraid not to have it done the next day. I couldn’t imagine coming in and saying, “Barbra, I didn’t do it. I couldn’t. It didn’t come to me.”

My favorite part of the whole thing was when we would sit there and she would read the part of the psychiatrist and I would read the part of the coach. I was her costar for a couple of weeks. How many writers get to live a fantasy life like this?

After we would read a scene, she’d say, “You know, my lines sounded better to me.” I said, “Well here’s the reason: You won an Academy Award and I’m just a guy. You’re always going to sound better.” When she went over a scene, she would close her eyes and she could feel where it broke down. She would pick out a weak phrase. It was just wonderful watching an artist at work.

Barbra asked me every question she had in those two weeks. She just plunged right in. The first day she asked, “Was I your idea for Dr. Lowenstein?” I said, “No.” Then she pointed to a video monitor. She had done her own screen test in which she was dressed as the character. She said, “Does that look like Dr. Lowenstein?” I said, “Yeah, that’s her.” It was the first time I could imagine Barbra in that part. She showed me other actors and actresses she was casting. She showed me a kid, a very good actor, that she had hired to play her son. He was a good-looking kid and a really good athlete. I said, “Barbra, that ain’t the guy.” She told me she had already hired him. I said, “You can do whatever you want, I’m just telling you, that doesn’t remind me of the kid. This kid is supposed to be having trouble. He’s kind of snotty.” So she showed me some others, including a screen test that her son did, though she didn’t tell me it was her son. I said, “Man, that’s the kid. That’s the guy I’d choose.” So that was my only casting choice.

When I first heard Barbra had gotten the rights to the book, I thought it was going to end up being a story about a New York psychiatrist. But she handed the movie as a gift to Nick Nolte. I was [surprised] when they told me Nolte had been cast [to play the coach, Tom Wingo]. I had just seen him the night before in Q&A, where he reached his hand down and grabbed a transvestite’s genitalia. I thought, Holy God, he is going to play Tom? I just had no idea he had this range. And he knocked me out. I was totally wrong about him. Now, I can’t see anybody else in the part. This is how powerful a movie is: I can’t think of my own characters without thinking of Nick Nolte and Barbra Streisand.

Here was what surprised me most about Barbra. The first day I was with her, she asked me question after question about the book. I remember she asked me about this reference to the Carolina Shag. I said, “Well, that’s how we used to dance in South Carolina when I was a kid.” So she asked me to teach it to her. I said, “Barbra I feel like a bit of an idiot.” She said, “just go ahead.” And it was fun. You see, what I did not know about her was that she has an incredible sense of fun. Like everyone else, I had read stuff about her. I thought, Holy God, I am going to be working with the Bride of Frankenstein. I thought she would yell at me, hurt my feelings, slap me around. I was completely stunned to find out that she was a delight.

But all the people who work with Barbra closely have been with her for thirty years. That should have told me something. She inspires great loyalty from the people who are around her. Her birthday came [when we were working together]. What amazed me was the number of flowers she received from her ex- boyfriends. She keeps up with them. They like her. She likes them. The notes they sent were lovely, really loving. There are many of my ex-girlfriends that do not do that with me. I would like to say that I gave her the biggest bouquet of all, but these Hollywood guys could whip my fanny. Like Jon Peters. I didn’t think there were that many roses alive in New York City.

Normally [when a book of mine is turned into a movie] I miss the language, but Barbra used music for language. We were working on the script one day when a call came in from the violinist Pinchas Zukerman, who was doing some of the music for the movie. There was all this amazing audio equipment [in the room] so I could hear him [play] and Barbra told me to stay and listen. Zukerman started playing “Dixie” like [Lowenstein’s husband, Herbert Woodrouff] does in the book. Suddenly I felt such guilt about writing that scene. Because I wrote that in the book, Pinchas Zukerman had to play it. When he finished, Barbra said, “You are not playing it right, Pinchas.” So Pinchas, who has a heavy accent, said, in this very dignified voice, “Barbra, what do you mean I’m not playing ‘Dixie’ right? Is there a right way to play ‘Dixie'?” She said, “I want verve and snap. I want it to be ironic.” He did it again and again, but could not satisfy her. So she said, “Let’s go on to something else.’ They started to work on the music for the scene in the train station where the son plays the violin. I think it was Bach. So Pinchas plays it beautifully, it is just meltingly beautiful music. I can see Barbra is listening so intently. I mean, she is taking in every note. When he finishes, she says, “It’s not quite right. Here is how I would like it to end.” And then she hums. There was a pause on the other end of the phone, then Pinchas said, “Barbra, Bach did not write it that way.” She said, “Pinchas, I don’t care, I’m the director. I want you to play it that way.” So he did. I’m afraid to say this, because I had the same problem as Pinchas did —Bach did not write it that way. But I have to admit, it sounded great.

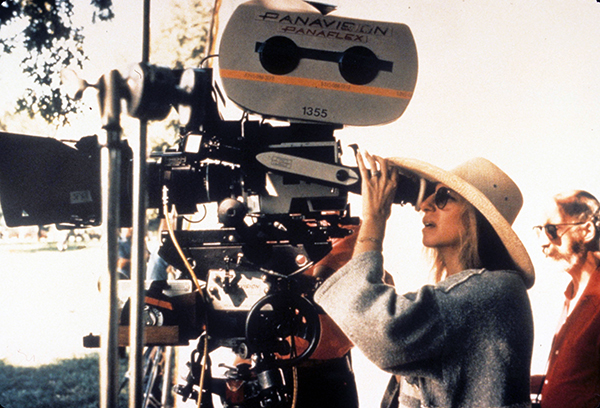

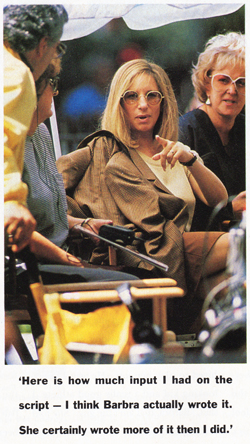

It was that kind of amazing attention Barbra gave to detail. She put her mark on everything. By the time I had gotten there, she was in the middle of it: the wardrobe, the shoes, the earrings . . . Oh yes, Barbra is a part of it all. I’ve never seen anyone go through a total immersion in a project like she does. It completely obsesses her and takes over her life. I mean, here is how much input I had on the script — I think Barbra actually wrote it. She certainly wrote more of it then I did. She whipped that thing into shape the way she liked it, and I just helped with the polish. She should have taken a screenwriting credit on it. I think she even tried for one, but the Writers Guild works in Byzantine ways, which I don’t understand. She certainly deserved it.

Writing a screenplay is a very different art form. I understand that changes have to be made. And I do feel that Barbra honored the book by her interpretation. There were maybe two scenes that she put in that I just said, “Oh . . . ” One of them had the psychiatrist and the coach walking down Fifth Avenue holding hands and kissing, with Indian headdresses on. I told her if she put that in, I would never speak to her again as long as I lived. But here is the thing, if there had been a fight between me and Barbra Streisand, it is my theory that Barbra would have won hands down and that the studio might have backed her. But she was very nice about it.

Overall, the experience was great. Barbra looks good, she smells good. And when I was around her, I lived nicer than I have ever lived in my life. I looked out on nicer views then I normally look out at, I ate better food, I walked on better rugs, I sat on nicer chairs. It was just terrific. When Barbra enters a room, the whole atmosphere changes. Stars appear in the East. Magi begin moving towards the room like camels. Women will follow her to the restroom.

Besides, since Barbra has come into my life I can name-drop in a way I never could before. And people just love listening to it. I can say, “And Barbra said ...” and, like an E.F. Hutton ad, I can feel them all lean in.