TV Guide

August 20—26, 1994

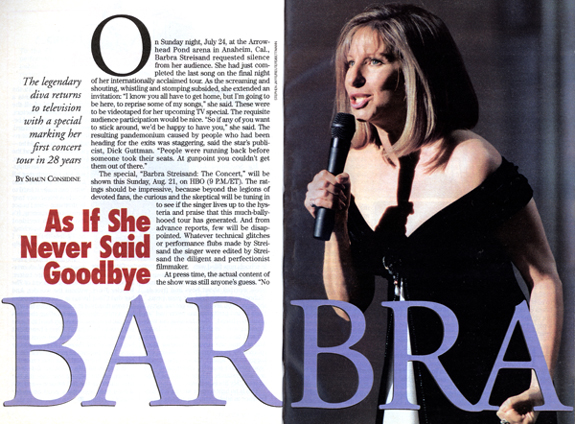

As If She Never Said Goodbye The legendary diva returns to television with a special marking her first concert tour in 28 years

BY SHAUN CONSIDINE

Sunday night, July 24, at the Arrowhead Pond arena in Anaheim, Cal., Barbra Streisand requested silence from her audience. She had just completed the last song on the final night of her internationally acclaimed tour. As the screaming and shouting, whistling and stomping subsided, she extended an invitation: "I know you all have to get home, but I'm going to be here, to reprise some of my songs," she said. These were to be videotaped for her upcoming TV special. The requisite audience participation would be nice. "So if any of you want to stick around, we'd be happy to have you," she said. The resulting pandemonium caused by people who had been heading for the exits was staggering, said the star's publicist, Dick Guttman. "People were running back before someone took their seats. At gunpoint you couldn't get them out of there."

The special, "Barbra Streisand: The Concert," will be shown this Sunday, Aug. 21, on HBO (9 P.M./ET). The ratings should be impressive, because beyond the legions of devoted fans, the curious and the skeptical will be tuning in to see if the singer lives up to the hysteria and praise that this much-bally-hooed tour has generated. And from advance reports, few will be disappointed. Whatever technical glitches or performance flubs made by Streisand the singer were edited by Streisand the diligent and perfectionist filmmaker. At press time, the actual content of the show was still anyone's guess. "No one will know," said an HBO spokesperson, "until Barbra comes out of the editing room.” The bulk of the special will be taken from the Las Vegas and Anaheim concerts, Guttman believes. Documentary footage of the tour may also be inserted, providing actual testament to how Streisand, after suffering through bouts of excruciating stage fright, finally got up the courage to appear live before a paying audience for the first time in 28 years.

Her fears were certainly conquered at the right price. The take from 26 concerts came to an estimated $70 million. Was money a motivation for this enterprise? Streisand herself hinted as much in December of 1991, when she told Tom Shales, TV reporter for The Washington Post, that she was considering singing again in public again for financial reasons. “I actually am running out of money, because I don’t work very often,” she said. “I bought all this land and I can’t sell my other land [her ranch in Malibu], so I might have to go out and sing just to pay for my house.”

Last August, a fortuitous call came in from Kirk Kerkorian, the owner of the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. He offered to donate $3 million to Streisand's favorite charities if she would consider performing for one night—New Year's Eve—at his hotel. Streisand mulled it over, with the help other longtime manager, Marty Erlichman, and a more lucrative plan was chosen. She would perform in Vegas for two nights, and film the spectacle for a pay-per-view TV special (the idea was later scrapped in favor of the HBO special).

In October, when the announcement of her Vegas appearances was made, the public and press went wild. Tickets to the two shows sold out in a matter of hours. By then, Streisand was already tackling the concept and logistics of the concert, which she would conceive and direct. The theme would be autobiographical, with a touch of the universal, she said. Through song, spoken narrative, and visual clips, she would take the audience on a kaleidoscopic journey through her life and career.

Rehearsals were held on a giant soundstage at Columbia Pictures in Hollywood. In attendance were 64 musicians, under the supervision of composer/conductor Marvin Hamlisch. As she rehearsed, Streisand was concurrently tackling two of her primary fears about performing live. One of these concerned her memory. Would it hold up? Sequestered for so long on Hollywood soundstages, Streisand was accustomed to scripted dialogue that could be filmed in brief one- and two-minute chunks. Onstage, where she would be expected to deliver a full-length program, without cuts or retakes, the only solution was to use a TelePrompTer. The second issue was her voice. In choosing to sing publicly again, she must have been terrified that she would not live up to her own high standards. This concern would not have been unfounded; both age and lack of practice do take their toll on divas.

A wondrous instrument, capable of captivating and beguiling the most jaded of ears, Streisand's voice and her innate interpretive talents have benefited—at least since she retired from the live stage performances and TV specials of yesteryear—from the controlled environment of the recording studio. Therefore, the challenge would be to create a similar environment for the concert space, via amplification and control boards. To make this possible, sound wizard Bruce Jackson, who had worked six years with Elvis Presley and 10 with Bruce Springsteen, was brought in to perform the painstaking acoustical work Streisand required. "I had heard that she was impossible to work with," said Jackson. "She was demanding, but I found if you give her what she wants, she is in fact a great pleasure, very stimulating." Creating the right acoustical atmosphere for Streisand took weeks, and the superstar used the time to bombard her sound people with constant questions and interrogations. "She knew what she wanted, but she didn't know how to get there," said Tom Gallagher of Aura Systems, who was hired to manufacture a speaker system for the concerts. "It was our job to keep experimenting until we got it right."

"She definitely kept everyone on their toes," said Jackson. "If you disagreed, you had to stand your ground. She would listen and try to rattle you. If you showed you were rattled and gave up ground, you were dead."

Having been given carte blanche to do whatever it took to make Streisand happy, Jackson had special monitors and audio equipment designed and manufactured to accommodate her exact vocal requirements. To achieve the intimate, controlled sound she sought, Jackson suggested they lay carpet on the floor and hang heavy drapes on the walls of the enormous arena she was to perform in. "I knew this would also be hugely expensive, but when I mentioned it to Barbra and Marty, they both said: 'Yes—do it.'"

Opening night in Las Vegas arrived. At 20 minutes past performance time, Streisand could be found backstage, calming her nerves by listening to meditation tapes. Waiting in the audience were such celebrities and notables as President Clinton's mother Virginia Kelley, Coretta Scott King, Cindy Crawford, Richard Gere, Kim Basinger, and Alee Baldwin. As the overture began, final touches were made to Streisand's simple coiffure and couture gown. The corridors and passageway to the stage were cleared of all personnel, except for her security staff and her personal TV cameraman. As the overture came to a resounding climax, the house lights dimmed completely and she appeared, standing in her own golden spotlight, on top of the staircase of her cream-colored, Monticello-inspired parlor. "I don't know why I'm frightened," she sang. "I'm thinking how I've missed you …I've come home at last." The song was Andrew Lloyd Webber's "As If We Never Said Goodbye," and for the fans in the audience who'd been waiting 28 years for this moment, no sentiment ever rang truer. As the applause washed over her, Streisand made it down the staircase and proceeded to enthrall the audience.

"That Babs was understandably nervous only added to the electricity. That she was reading every word—even the spontaneous patter about how thrilled she was—from six monitors contributed to the event's irresistible surrealism," said Village Voice columnist Michael Musto, whose $100 ticket was paid for out of his own pocket.

The next night, Streisand was more radiant and relaxed. In viewing the TV footage the following week she said she was pleased—but would not commit to releasing it to HBO. The matter of taking the show on the road was also undecided.

It wasn't the lure of further huge revenues that made up her mind to tour, her publicist emphasized: "It was the connection with the audience, and the fact that she felt she could do it." Erlichman, accompanied by Jackson, went to seven cities, inspected each arena, listened to the best offers, then took the information back to Streisand. "They decided together, about the cities and the prices," said Guttman.

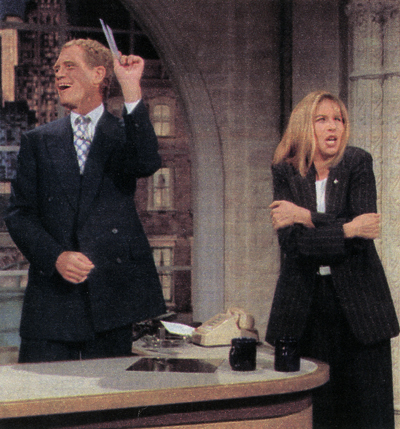

(Photo, above): It was like buttah: In 1992, Streisand surprised the ladies of "Coffee Talk" on Saturday Night Live.

When Streisand's record company, Sony, suggested she put her name and face on merchandise to be sold on the tour, Streisand initially balked, claiming she wasn't some "young hip rock person." But she quickly came around, personally designing T-shirts, baseball caps, women's scarves, and men's ties. She was so pleased by her creative efforts that, in addition to having the stuff hawked at her concerts, it was arranged that Sony Signatures would sell the entire line by mail-order and in special "Barbra Streisand Boutiques" set up in Bloomingdale's and other selected stores.

In March, when the tour dates were announced, tickets also sold out within hours. The steep prices, which topped out at $350 per seat, did bring some negative comments. "My Name Is Brazen" and "Greedy Girl" were some of the unflattering newspaper salutations. Streisand shrugged them off, rationalizing: "If you amortize the money over 28 years, it's $12.50 a year. So is it worth $12.50 a year to see me sing? To hear me sing live?"

The fans certainly thought so, including Paul Busa, a devotee from New Hampshire. He bought tickets to see her in Vegas, Washington, Detroit, and New York. Total cost: $4000, including expenses. And it was worth it. "I've idolized her since I was 8, and I figured this would be the only time I could see her live," he said. Tickets allotted to celebrity guests were carefully monitored. Favored celebrities were usually placed in the first three rows, where Streisand could see them during her performance. Some would be acknowledged with a smile and a wiggle of her fingers; some by name (to Liza Minnelli: "That [song] was for your mom"); and some by a loss blown softly from her fingertips (ex-boyfriend Don Johnson rated a kiss). Others were less fortunate. Fitness guru—and unabashed Streisand fan—Richard Simmons sent his idol an expensive ring during the New York leg of her tour—only to have it sent back.

In each city, Streisand arranged to have a hospitality room set up backstage, which was decorated with her own furniture. The names of the concert guests allowed backstage and into the hospitality room were subject to Streisand's approval. Some, such as columnist Liz Smith, a Barbra booster from way back, were approved, then crossed off the list at the last moment. Initially irritated, Smith said that her pique was soon overcome by the sheer power of Streisand's performance. In some cities, important politicians and civic leaders who managed to get backstage through the good graces of the arena's producer or promoter had a hard time getting into the hospitality room—especially if they were Republicans. In New York, even the former mayor, David Dinkins, a prominent Democrat, made it into Streisand's inner sanctum and was taken to dinner.

In April, accompanied by multiple trailer loads of sound equipment, 10,000-plus feet of gray carpet, her customized lighting, the palatial set, the crew and 64-piece orchestra, and her own staff (including personal trainer, hairstylist, and two bodyguards), Streisand arrived in London for the first of four appearances in Wembley Arena. The airport-style metal detectors set up at each entrance to the arena were used to detect and seize weapons, it was explained, including the Instamatic cameras that her fans carried to the show, hoping to take home a keepsake image of their idol. The London reviews, barring one or two negative ones, were glowing. Prince Charles attended, and was so tickled by Barbra's singing "Someday My Prince Will Come," that post-performance he rushed backstage, where the two exchanged compliments on how well the other looked some 20 years after their last meeting.

On April 24, Streisand turned 52, and was feted with a surprise party. The guests included Steven Spielberg, Carrie Fisher, and Michael Caine. Some crew members arrived with an unexpected gift: "We went to this classy underwear place and bought her an expensive black bra, a garter belt, black stockings, and a G-string," said one. When Streisand opened the package at the party and held up the G-string, there was a pause in the proceedings. "But she loved it, because most people are scared to treat her like a woman."

Back home for the start of her American tour, the star's staff was bothered by pesky reporters asking questions about the matter of concert tickets allotted to charitable groups. Some 9700 tickets had been reserved for various good causes, but the organizations had to pay $350 up-front for each seat, which they could then mark up to $1000 and resell. One charity leader commented, "It would have been much easier and cheaper if she'd donated them" —a sentiment loudly echoed in the press.

When she arrived in Detroit in May, the first signs of tour stress were said to be evident in the singer. The strain came from her multitude of duties. In her hotel suite each day, after critiquing the previous night's footage on video and dictating notes to be sent to sound, lights, and orchestra, Streisand turned her attention to the matter of the HBO special. Some 20 hours of documentary footage had been shot by her resident cameraman. Tapes of these were played and replayed for Streisand, which resulted in ever-changing instructions on where they could be intercut with the performance segments. The marathon workload eventually hit the singing star where it mattered most: Streisand lost her voice.

(Photo, above: Streisand paid a visit to David Letterman's show in June, presenting him with a pair of concert tickets.)

Resting in California, she whispered her wishes to her manager. Four of her Los Angeles concert dates would have to be postponed.

Sunday, June 19, found Streisand setting up for what she considered to be one of the most important stops on her tour: her hometown, New York City. Streisand announced that the sound in Madison Square Garden was unacceptable. The problem, she soon learned, lay in the carpeting. Upon inspection, she discovered it wasn't hers. "When we agreed to do Madison Square Garden, they showed us a sample of carpet and we said OK," said Jackson. "But when we came in, it was nothing like the sample. So Marty said: Take it out!'" It took five hours and cost $30,000 to pull it out and put down Streisand's own carpet. The results were worth it. Streisand was rewarded with seven standing ovations on opening night. Two days later, expecting some prominent coverage, Streisand's handlers were slightly miffed: O.J. Simpson, in his first L.A. court appearance, had taken the covers of all the Manhattan newspapers. Inside each paper, however, Barbra's notices were all raves. Buoyed by this, two additional concerts were scheduled in New York. The last night, a video simulcast of her closing song, “Somewhere," was beamed to the steamy populace in Times Square. This was another "gift to her fans," tour publicist Ken Sunshine explained. "She felt so good coming home, she wanted to make this one last gesture for the people."

Meanwhile, the HBO brass waited patiently for word on if and when they would have a completed show from Streisand. They were told to lock in two hours on Aug. 21. The idea of a live concert was discussed at one point. But that notion was scuttled when Streisand decided to go with the New Year's footage from Vegas. "It's the historic significance," an HBO spokesman explained. Additional songs were scheduled to be taped at the final concerts in Anaheim. The Streisand video cameras were prominent that last night, as were the famous faces in the audience: Warren Beatty, Annette Benning, Shirley MacLaine, and Paul Reiser. When asked to stay longer, their stellar participation was enthusiastic. "It was extraordinary because they repeated their standing ovations, with more fervor," said Guttman.

And so the Grand Tour, the Great Adventure, "The Concert," was over. It was hoped that Streisand the director—known to dally in the editing room—would get the completed tape to HBO on time. All that would remain then were the reviews from the TV critics. More important to HBO and Time Warner was, how many new subscribers would the special pull in? And for the merely inquisitive: What happened to the 10,000-plus feet of carpet? "They're selling it off as 'Barbra Streisand's carpet,'" joked one source.

Shaun Considine is the author of "Barbra Streisand: The Woman, the Myth, the Music" and "Mad as Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky."

END.

Related: Barbra's 1994 Concert Page