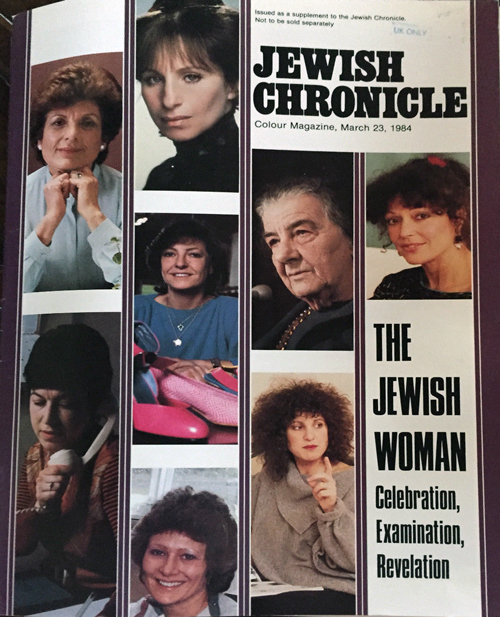

The Way We Were

Jewish Chronicle

March 23, 1984

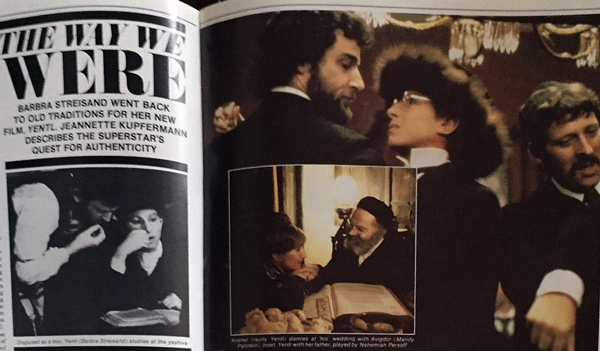

Barbra Streisand went back to old traditions for her new film, Yentl. Jeannette Kupfermann describes the superstar's quest for authenticity

I want it to be as authentic as possible. This was one of the first things I heard Barbra Streisand say about Yentl, the film she both stars in and directs and which opens this month in London.

Authenticity is an elusive quality that Hollywood directors invariably strive for but, somehow, only rarely manage to achieve. To this end, they will employ technical advisers, consultants, historians, and other experts to make sure that what looks good on camera is also technically and historically accurate. Barbra, whose reputation as a perfectionist is second to none, was no exception in her determination to recreate the vanished world of East European Jewry.

The original Bashevis Singer story of the girl who disguises herself as a yeshiva bocher, although atmospheric in the extreme, only barely delineated the details, and had an almost two-dimentional quality. In films, of course, all the detail has to be provided. Much of this work was done by Barbra herself who spent long months poring over old photographs, books and archive film before conferring with her costume and set designers and script writers (her final collaborator was writer Jack Rosenthal).

As well as the library work, she attended study groups in Los Angeles, consulted rabbis (Rabbis Louis Jacobs and Harry Rabinowicz in this country) and yeshiva students (taping all conversations), and visited museums and centres like the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York. In her own words, “it was a complete education,” and she told me that she hoped to continue that education.

“If Barbra had had her way with authenticity,” commented production designer Roy Walker, “the film would have looked like a documentary.” She wanted genuine hand-embroidered petticoats from Europe and wanted to find genuine East End Jewish tailors to do the costumes until persuaded otherwise.

Some of this enthusiasm, too, had to be tempered by considerations like Equity rules about using only their own members. Take the case of the dancers in the wedding scene. Originally Barbra wanted to use members of the Chasidic community themselves, and had been delighted with a group of youngsters roped in from all over London by Judah Gastwirth, the leader of a group of Jewish musicians. They came along dressed in colourful costumes to perform for Barbra and choreographer Gillian Lynne, hoping they would be used in the film. They demonstrated basic Chasidic steps to Gillian Lynne who then, alas, had to adapt them for the professional dancers demanded by Equity.

To get the feel of the music, movement and crowds, and also because of the wedding scene in the film, Barbra would try to attend as many Chasidic weddings as she could possibly find. “Can you find me a wedding?” became a familiar request—and it was not easy when she specified exact dates. It was no good protesting that weddings were made in Heaven and not for film crews, and I would desperately scan the Jewish papers, and phone around all my ultra-Orthodox contacts in the hope of “finding” one.

I usually managed it and then my next task would be to procure as many invitations as possible without giving away the Big Name (for at the last minute I was bound to get a request for six extra invitations—one for the casting director, one for the lighting cameraman and so on, and it was no good explaining that film crews generally were anathema to the more traditionally minded).

Like a general planning an invasion, I had to think of ways of camouflaging, disguising and “landing” people so that no one would guess my real objectives. Like a general, too, going into battle, I would lecture my troops beforehand on proper dress and behaviour, for I still had memories of one near disaster when, once before, attempting to smuggle a film crew into a Stamford Hill wedding (working for Fred Zinnemann who was planning to make The Dybbuk), I had, at the eleventh hour, to persuade the very Goyische-looking blond art director to dye his hair, and to find a hasty cover-up for the casting director who arrived in a sleeveless, see-through blouse ...

I think even A Bridge Too Far must have been easier.

But nothing quite equaled one wedding I had managed to get Barbra and some of her crew invited to at the Stoke Newington Town Hall. I still blush to tell the tale. I gave my usual briefings to all concerned:

“Please wear hats (I described the type) and dark suits—but especially the hats—don't forget.”

“Where do we find them?” they had asked.

“Anywhere you can,” I had said.

I arrived first to survey quickly the scene in the courtyard at the back, where bearded and shtreimelled guests were fast arriving, and tried to look as inconspicuous as possible.

Imagine my horror when I saw advancing towards me two figures who looked distinctly like they'd wandered in from the local circus. One was wearing what looked like a bright red hunting jacket, carnation in buttonhole, floppy bow-tie and bowler. The other, hatless, was carrying a vast plastic bag almost as big as he was, marked BERMAN'S THEATRICAL COSTUMERS, full of—you've guessed—HATS of all shapes and sizes.

There was no time to explain—all I could finally stammer was, “Hide yourselves in an upstairs gallery or somewhere ... you'll be recognised.” I went outside into the courtyard again to find that dusk had mercifully fallen, and as the bridegroom was mobbed by the crowd, black jackets, red jackets, homburgs or bowlers didn't matter much. Barbra, in any case, had changed her mind about coming and next time I would lay my battle plans more carefully!

The main problem, of course, taking Barbra to a wedding incognito, was keeping her identity secret, as the famous profile was something of a giveaway, even when, as she often did, she wore hats that hid most of her face, and dressed fairly inconspicuously.

At one wedding at the Wembley Town Hall, all seemed to be going well as I introduced her as a friend, Mrs. Peters, and she sampled cherry brandy and advocaat (for the first time, it seems) and waxed eloquent over the fish balls. But there's always one maven who has seen Funny Girl 20 times (even among a supposedly non-filmgoing population), and here she was, giving Barbra a distinctly fishy-eyed stare over the herring.

“Aren't you that actress ... you know the one?” she eventually asked, to which Barbra was quick to reply in cut glass English tones, “No I'm not, though everyone always thinks I am,” before taking refuge in the ladies.

“That was a good English accent,” I congratulated her, but Barbra wasn't too happy with her ruse. “I hate to do that to people—they're always so disappointed when they find out,” she sighed.

She needn't have worried, however, for there was our beady-eyed friend, who, undeterred, had followed Barbra right into the cloakroom and was about to cry triumphantly, “You are her—I know you are.” Well, there's no arguing with that, so Barbra took a deep breath and admitted she was indeed the lady in question.

Needless to say, she was a great hit with all the gorgeously attired Chasidic matrons at our table, who were greatly flattered by Barbra's interest (professional, of course) in them. Barbra, in fact, left them fairly breathless with her questions:

“Is that really a sheitel?” she would enquire, sticking one finger under the elastic of a magnificent upswept coiffure. “You must give me your wig-maker's name,” or “Say, could you tell me about Havdala candles?”

They even exchanged notes on jewelry (Barbra being a great collector of art deco pieces), and there were the inevitable invitations proffered for the Friday night meal.

If Barbra herself has a genuine love for the heimische, she tried to encourage it equally in all her cast. Mandy Patinkin, for example, her co-star, was encouraged to visit Yeshivot both in North London and Israel to get a real feel for the part. Barbra even instructed Yeshiva students to come in to talk to him informally about such things as how they coped with their sex lives (an important part of the film, which hinges round sexual ambiguity). I remember being banished from her office on that occasion.

“I wanted people around me who had the right spirit—and the right soul,” she would say. And one did feel that everyone involved, Jew and non-Jew alike, brought an intense commitment to the film, largely stemming from Barbra's own passion for steeping herself in every aspect of Yentl.

For my part, so authentic was the look of most of the people involved that I never quite recovered from the shock of wandering into the Lee Studio canteen one breakfast time and seeing it full of bearded, caftaned extras, wearing yarmulkas or hats, eating their bacon sandwiches; nor, for that matter, of going on to the “Vishover” house set, and seeing the sideboards laden with Bloom's “wedding” food, which unfortunately had to remain blistering under hot lights.

Ultimately, there will be those who say that the music sounds more Hollywood than Chasidic; that the sexual encounters are more explicit than anything Bashevis Singer ever dreamed of—and they will be right. But the warm feeling, the vibrancy of shtetl life is there, with Barbra herself at the centre, an apt symbol of a third-generation American who has discovered that roots matter after all—perhaps most of all.

END.

Related Links: