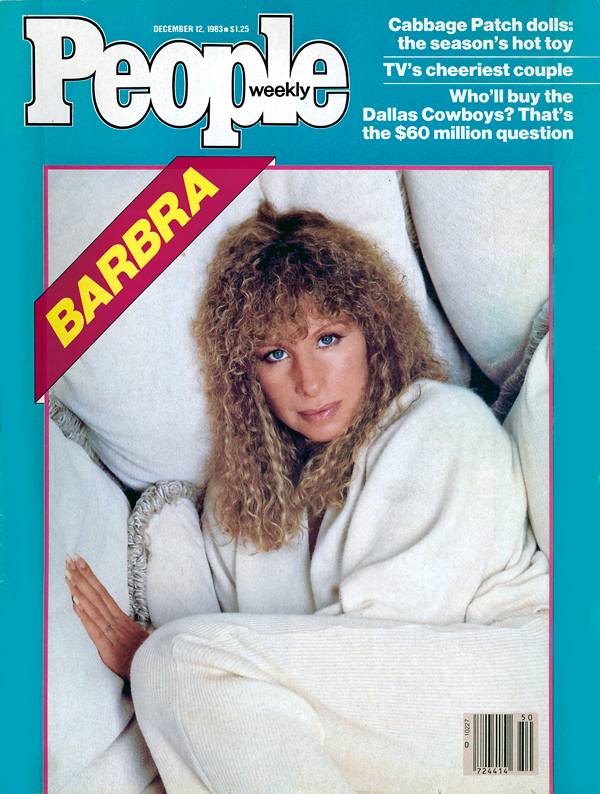

December 12, 1983

Barbra Streisand sounds off about her Yentl critics, her troubles with Jon Peters and the only man she lives with now—her son, Jason.

CELEBRATION OF A FATHER

Barbra Streisand resurrects her past in her hit movie Yentl, and, at 41, comes to terms with life and loving

by Brad Darrach

The lady was on the hot seat and she was squirming. For weeks show business had buzzed with rumors that Yentl was just a big soggy Central European knish, that, in her first effort as a director, Barbra Streisand had grabbed all the major screen credits and wound up, as one wit snapped, "with ego on her face." Yet friends who had previewed the picture had been overwhelmed by Yentl—or so they told Barbra. Jane Fonda said she was in tears when the movie ended, and Steven (E.T.) Spielberg hyped it as "the best directing debut since Citizen Kane." Early reviews ranged from ecstatic to mixed. Then came the review by Janet Maslin in the New York Times. It was a crusher: "Barbra Streisand wears a pillbox-contoured designer yarmulke... Technical sloppiness is evident throughout."

Barbra blew her stack. "Technical sloppiness! If there's one thing professionals praise in Yentl it's the technical quality. And that so-called designer yarmulke is an authentic one of the period. How can anybody not check such facts and be a critic?" Barbra bristled: "It's mostly the women reviewers who are attacking me. Can't they stand to see another woman succeed?"

The morning of the day Yentl opened, Barbra was thoroughly spooked. "I said the hell with it. I ran out and bought all the chocolate-covered marzipan and walnut cookies I could carry and sat there and stuffed myself. That's how scared I was."

(Photo, right): Barbra keeps finding new ways to scare herself. She was a scared child of 19 when she took to the Broadway stage and, boldly exploiting her big Jewish nose and delicatessen accent, won all hearts in I Can Get It for You Wholesale. And now, at 41, the lady was more scared than ever as she watched the roll of the dice on the biggest gamble of her life.

Against the massed opposition of Hollywood's production establishment, and after a hugely expensive struggle that persisted for 15 years, Streisand has done what no one has ever done before: She has written (with Jack Rosenthal), produced, headlined and, for the first time in her career, directed a major Hollywood musical. On top of which, she has sung all nine songs in the show and recorded the album.

What makes Streisand run such risks? Her motives lie concealed in a grab bag of incongruities. Talent to burn. A furnace of emotions. Sometimes waves of shyness, attacks of dread. Sometimes traits of the petty despot—need to control, nit-picking perfectionism, incessant suspicion, incessant testing. Always a sense that behind the power and possessions hides a lonely and angry little girl.

Whatever it may be as a movie, Yentl is also an urgent and brave attempt to sort out this fascinating mess, a singular public act of self-analysis and self-reclamation. The idea for the film first struck Barbra in 1968, when she read a short story called Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy, by Nobel Prize-winner Isaac Bashevis Singer. It's a tale about a Jewish girl in turn-of-the-century Poland, whose scholar father teaches her Talmud (a study forbidden to women) with the blinds drawn. When her father dies, Yentl disguises herself as a boy so that she can enter a yeshiva, inconveniently falls in love with her study partner and then improbably finds herself marrying the woman her partner loves.

The story gripped Barbra from the moment her eyes moved over the first words: "After her father's death ..." Memories came crowding back. With painful intensity she began to relive her childhood.

Barbra's real father, Emanuel Streisand, who was the son of an immigrant fishmonger, earned a master's degree in education at Columbia University and taught English literature at a Brooklyn high school. He was an athlete as well as a scholar, a big, strong man who crowded the apartment with energy when he came home at night. Baby Barbara (as her name was spelled then) adored him. But one night, when she was 15 months old, her father didn't come home. At 35, he was dead. For reasons still obscure, but probably rooted in the superstition that epilepsy is a shameful affliction, Diana Streisand, Barbara's mother, said he died of a cerebral hemorrhage brought on by overwork, an untruth that caused Barbara and Sheldon, her older brother, to live in dread for almost 35 years. "I thought I might die of overwork too," says Streisand. Actually, as Barbara's mother finally admitted, their father died of respiratory failure probably induced when morphine was injected into his neck to halt an epileptic fit.

Barbara was too young to understand the tragedy, but for weeks after her father died she would toddle to the front window every night and wait there, hoping to see Papa come home. In a little while she forgot he ever existed. "I always felt I never had a father," she says. "There wasn't even a picture of us together. Only his books down in the cellar, tied up with string." If she thought about him at all, it was to resent him for making her "the only kid on the block without a father."

One loss led to another. "Emotionally my mother left me at the same time—she was in her own trauma." Destitute after her husband's death, Mrs. Streisand took her two children and went home to her parents. They had a tiny, three-room apartment, much too small for five people, on Pulaski Street in Brooklyn. "I slept in a bed with my mother," Barbra remembers. "I never had a bedroom to myself until I was 16." Sheldon, now a successful real-estate operator, says his grandparents were "decent, hard-working people, but there was no love in that house. I remember there was a huge table in the dining room and Barbara and I would scuttle under it to avoid beatings."

Mrs. Streisand was a distant figure, away at work all day and tired when she came home, and to make matters worse, she refused to praise her children for fear they might get "blown-up egos." Barbara became lonely and confused. "I didn't have any toys to play with," she remembers. "All I had was a hot-water bottle with a little sweater on it. That was my doll."

In 1950, when Barbara was 7 1/2, her mother married a used-car salesman named Lou Kind, who actively disliked his predecessor's homely, needy little leftover. "He was really mean to Barbara," Sheldon remembers. "He taunted her continually, telling her how plain she was compared to Roslyn, her little sister, who was his daughter with my mother." Barbara stayed out of the house as much as she could. "Growing up," she says, "I used to wonder— what did I have to do to get attention?" Before she was 10 she found out. "When I started to sing I got attention."

(Photo, left): After her husband's death, Barbra's mother, Diana, remarried and had Roslyn. All three showed up to make a family picture at the Los Angeles premiere of Yentl.

But she got no encouragement at home. Her mother said her voice was too weak. When Barbara announced that she wanted to be an actress, her mother told her she wasn't pretty enough; she should learn typing and be a secretary instead. Defiantly, Barbara grew her nails so long she couldn't type and then signed up for a season of summer stock. She says she also began to dress like a bizarre creature, daubing her eyelids with blue crayons and dying her hair red, blue and green. Schoolmates called her Crazy Barbara. At 16, she finished high school with honors and "made her escape" (as Sheldon puts it) to a Manhattan acting school. Two years later she entered a singing contest in Greenwich Village, and almost before she could change her name to Barbra it was up in lights.

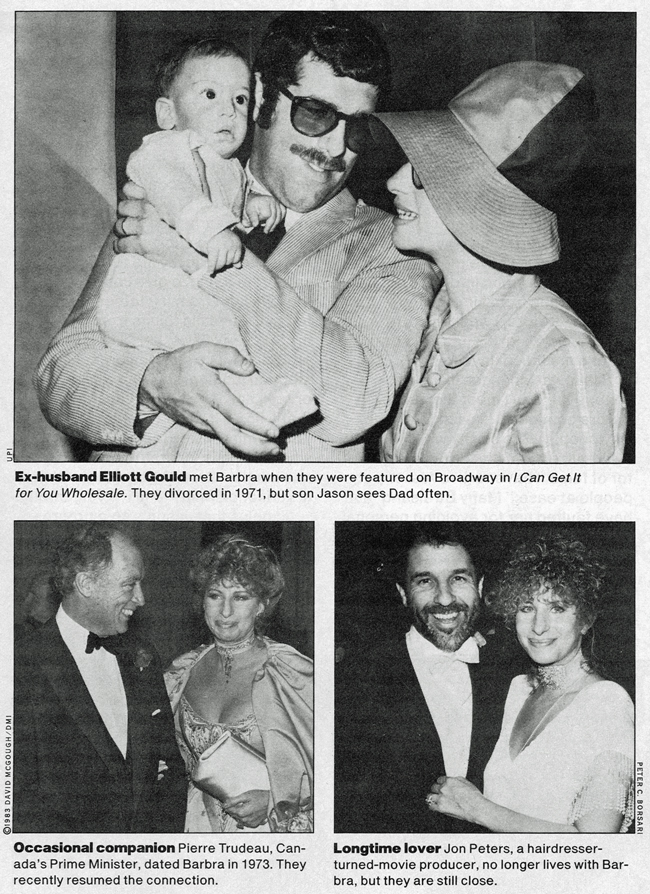

Streisand seldom looked back— never so far back as the father she had never known. She was too busy becoming a conglomerate of stage, screen, television and records; making and breaking a marriage to actor Elliott Gould; having and raising a son named Jason, 17 this month. But then, at 26, she discovered Singer's story, and the dead rose up to haunt her. Impulsively she began to plan a movie based on Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy.

From that moment problems beset the project. Author Singer, a bossy old party of 79, scolded her for daring to make a movie of his story. "What do you know about Poland, the Talmud? You're an actress. Make a movie about acting!" And there were endless problems with scripts. Singer's story is misanthropic and depressing. Streisand envisioned a movie that would be feminist and uplifting—"a poem to my father." But writer after writer failed to deliver the poem she wanted. Over the next 10 years Yentl was rewritten eight times.

At intervals between 1968 and 1979, Barbra offered her project proudly to six different studios. To her astonishment, all turned her down or scrooged the budget till it bled. They doubted that the public of the 1970s would sit still for a film in which a woman married a woman; that an actress pushing 40 could play a teenage boy; and, above all, that Big Bad Barbra, the legendary femme féroce who kept a freezer full of her former directors, would be able to subordinate her ego to the needs of other performers.

By 1979 Barbra was ready to abandon Yentl. But one night she had a bizarre experience that set the project back on track. "I had never seen my father's grave," Barbra says, until one day my brother took me there. After 35 years it was a strange experience. But that night I had a much stranger experience. My brother invited a medium, a nice, ordinary-looking, Jewish lady with blond hair, to his house. We sat around a table with all the lights on and put our hands on it. And then it began. The table started to spell out letters with its legs. Pounding away. Bang, bang, bang! Very fast, counting out letters. Spelling M-A-N-N-Y, my father's name, and then B-A-R-B-R-A. I got so frightened I ran away. Because I could feel the presence of my father in that room! I ran into the bathroom and locked the door. When I finally came out, the medium asked, 'What message do you have?' and the table spelled out S-0-R-R-Y. Then the medium asked, 'What else do you want to tell her?' And it spelled S-I-N-G and then P-R-0-U-D.

"It sounds crazy but I know it was my father who was telling me to be brave, to have the courage of my convictions, to sing proud! And for that word S-0-R-R-Y to come out—I mean. God! It was his answer to all that deep anger I had always felt about his dying."

Not long after this encounter, United Artists offered Barbra a $14.5 million budget—lean but workable if she paid Streisand the director the Guild minimum ($80,000) and persuaded Streisand the superstar to accept a relatively modest $3 million for five months work. So here it was: the decision she had dreamed of but dreaded. "I was terrified I would fail," she says. "But I was tired of playing it safe. I had already spent $500,000 of my own on Yentl. How many things do you believe in with that kind of passion?"

Yet there were negative considerations. If Barbra made the film, she would have to make it, in order to save money, in England and on the Continent, and that would involve more than a year's separation from her son. "If I make the picture," she asked Jason, "will you come with me and go to school in London?" Jason said no. He didn't want to leave his school and his friends. Barbra's therapist said it was a good time for Jason to separate from mother. "I had to let go," she says.

Making the film would also involve a separation from Jon Peters, now 38, the man Barbra had lived with for about eight years. A former owner of hair salons who had become a successful film producer (Missing, Flashdance), Peters is a complex and controversial figure. "He's a predator," says a former production colleague. "Sharp, imaginative and vulgar. But he's been important to Barbra because he's said no to her. They fought like tigers. Most of the time they lived on an adrenaline high."

Barbra has another view of Peters. "He's very strong," she says, "but he's also sensitive and creative. And he has a great zest for life. He loves to build things, and so do I."

(Photos, top): Ex-husband Elliott Gould met Barbra when they were featured on Broadway in I Can Get It for You Wholesale. They divorced in 1971, but son Jason sees Dad often. (middle): Occasional companion Pierre Trudeau, Canada's Prime Minister, dated Barbra in 1973. They recently resumed the connection; (bottom): Longtime lovor Jon Peters, a hairdresser- turned-movie producer, no longer lives with Barbra, but they are still close.

They built five homes in different styles on their 24-acre ranch in Malibu. "We each built our own," explains Barbra, "because we fought too much when we built our first one together."

The Streisand/Peters affair was passionate, sometimes violent. Jon says Barbra once hit him with a chair, and sometimes when he was furious, he grabbed her and shook her hard. "By the time we had been together for eight years," Barbra said recently, "our relationship had reached a turning point. We were butting horns because I was passionately involved in Yentl, and neglecting him. We had also been too dependent on each other. And you come to resent dependency. We needed to be apart."

So why did Barbra still hesitate to go off and film Yentl? "I needed a direct challenge," she says. "Somebody like my mother to tell me I couldn't do it. Then I'd get mad and do it. Jon gave me the challenge. He told me straight out I'd never make the picture."

Streisand signed the deal with United Artists, and her obsession with Yentl became a mania. She charged off to Czechoslovakia to scout locations, flew to London to assemble a staff of top technicians. Back home she rewrote the script with Rosenthal and plowed through interviews with actors, among them co-stars Mandy(Evita) Patinkin and Amy (Carrie) Irving.

Despite all these persnickety preparations, Streisand arrived on the London set in a nervous sweat. "I knew how many kinds of things you had to know to direct a movie," she says. She also knew that her reputation as a bitch had preceded her. But, from day one, the company was impressed by Barbra's white-hot dedication and her willingness to share power. "We saw that she really wanted to know what we thought, so we really told her," says Patinkin. "She was demanding, yet flexible and compassionate, with the gentleness of a woman."

Two things amazed everyone. One was Barbra's uncanny ability to jump back and forth between roles as a director and actress. The other was her stamina. For five months she was up at 5 a.m., put in a full day before and behind the camera, then watched the dailies—and after everyone else was in bed she sat up until 2 a.m. preparing the next day's scenes.

"She never got more than four hours sleep," says Patinkin, "and usually three. We were concerned for her. Yet she never flagged and looks wonderful on film. Some mysterious power sustained her." Barbra says simply, "It was my father. He watched over me."

He watched her so well that Barbra now has a giant hit. Almost all the critics hailed the film's technique and artistry. In its first 10 days of limited release, Yentl grossed more than $1 million, and even before the movie opened the Yentl LP had sold out its initial printing (600,000 copies).

One sunny afternoon, just before the Yentl premiere, Streisand is taking lunch on the glass-walled poolside terrace of her Holmby Hills mansion, a room so crowded with pink ruffles— ruffles on chairs, sofas, curtains, even on chandeliers—that a visitor feels like a very small bee floundering in a very big pink rose. Barbra is wearing an elegant cream-white caftan that neither seized nor ignored some very scenic top(and bottom)ography. Over a Chinese chicken salad she tries to sum up the Yentl experience.

"The work in itself," she says, "was wonderful. Making something where nothing was before. It's like being pregnant—every moment is creative. And frightening. And exhausting." Has the experience changed her? "Tremendously. I was in such pain before, so confused about myself. There's such an enormous amount of self-hate in actors, you know. People who need to pretend to be somebody else. I had a lot of self-pity too. But that's gone now." And the break with Peters has proved positive. "Before I was afraid to be alone," she admits. "There was a void inside me. Now I have myself. I feel filled from within."

She credits her father for much of the change. "In some way," she says, "my father and I have merged. He has passed his essence into me. I got the love I needed from him, and now I have it to give. Before, I was driven; now I'm doing the driving. It's easier to be around me these days.

"I think the changes in me will change the way I meet the public," Barbra continues. "I used to wonder why people were so shy with me. Now I've realized that it's the isolating factor of fame. I have to give first to put people at ease." Many Streisand fans have faulted her for avoiding personal appearances and concerts, where they can see her up close. Barbra acknowledges the fault. "The reason I haven't given concerts is because for years now I've been afraid to get up in front of all those people. But someday I will give another concert. I want to go back to the stage too and play Ibsen, Chekhov, Shakespeare. Roles that are bigger than I am, that I have to live up to."

Stirring her decaffeinated coffee with a tiny gold spoon—one of a dozen she bought (for $1,000) with the first money she earned as a singer—Barbra turns to the subject of men. "My son is the man in my life now," she says. "I'm trying to give Jason some of the love I got from my father. Before, I felt guilty and hid things from him—all my fears, my flaws. I tried to play mother. But now I've stopped preaching, stopped judging. I tell him what I think or feel, and if he doesn't accept it, that's fine." It wasn't always so. "Something inside me used to cut off when I felt misunderstood or denied," she admits. "Now the love is just there. It's unconditional—and It's very strong.

"It helps that Jason's an extraordinary person, very gifted at music and drawing. But I think the art he loves best is film. Soon he'll go to college, and I think I'll go too. I love math, languages, psychology and philosophy. I've never had enough of those things."

(Photo): Sadie, Barbra's toy poodle, enjoys a romp with the lady of the house on the glassed-in terrace where Barbra often lunches.

After lunch Barbra wanders into her formal art nouveau parlor, a spacious high-ceilinged room designed as a setting for a spectacular (and priceless) Tiffany lamp that looks like a metal tree with a blood-red crown. With family on her mind, the subject of Jon Peters comes up naturally. "We're not living together, but we're better friends than we ever were," she says, and her voice is warm. "We're much less competitive, more respectful. We've realized that we're both powerful people. I can't control him, he can't control me. We'd been taking each other for granted, the way people do when they live together for a long time. We don't do that anymore. What I want is a relationship between equals." Will they live together again? "We don't know what's in store. We're just trying to grow."

Barbra moves on to a room she has recently renovated. The room is white and so is everything in it. In her white dress, Barbra looks like a small cloud drifting through a large cloud.

Is she seeing any other men? "I'm seeing some. I'm learning to have dates. I'm having the adolescence I missed because I was so troubled as a girl and then had such an early suc cess. I sometimes feel like a 41-year- old teenager."

She speaks carefully of her friendship with the Canadian Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau. "We used to see each other years ago, and we've seen each other again," Barbra says. Is the relationship an important one? Barbra is silent for about 20 seconds. Then she answers: "I would say—no."

"Thinking about men," says Barbra, and now she is smiling gently, "I realize I'm much more compassionate toward them than I used to be. I'm not competitive now. I love our biological differences, and I don't want to be a man. To be liberated women doesn't mean just to use our minds. We have wombs and hearts as well as minds." Barbra pauses, looking thoughtful. "I'd like to have another child," she says firmly. "My idea is to adopt a little girl. Now that I'm back in touch with my father, with all he means in my life, I think I'm better equipped to be a parent than I was before. And I want to pass on the love that somehow my father has passed on to me."

End.

[ top of page ]