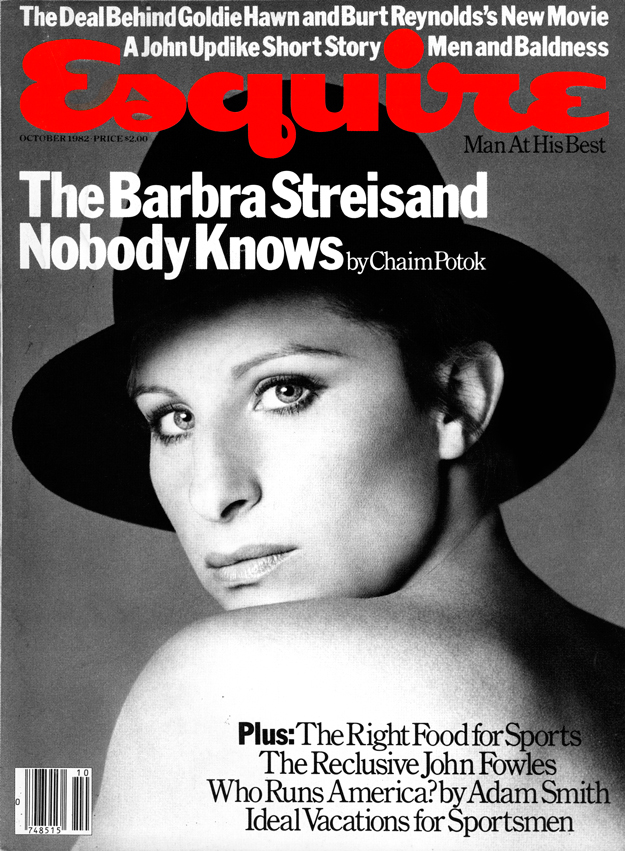

Esquire

October 1982

BARBRA STREISAND AND CHAIM POTOK

On spirituality, fears, illusions, and how actress and writer can best use each other by Chaim Potok

(Cover photo by Scavullo)

On a warm autumn night, the stars concealed by high clouds, I am being taken by car to a reception in the home of Barbra Streisand, who sponsored the lecture I delivered earlier in the evening at the University of California in Los Angeles. I carry within me visions of fabled Hollywood parties, feel a deep sense of unease and, at the same time, an openness to this new experience. Also, I have been told that Barbra Streisand is studying Talmud, is supporting a Hebrew school, has celebrated her son’s bar mitzvah – activities that are not usually associated with superstars.

I am curious about Barbra Streisand. Inside the house, all seems a dreamlike landscape as I move through richly furnished carpeted rooms and spacious hallways. Food and drink are in abundance. The decor is luxuriant art deco. Watteauesque paintings in ornate frames adorn the walls. The crowd is large but seems no different from party crowds anywhere, is perhaps even more subdued than most. I hear much sober talk about censorship and the Moral Majority. Familiar movie personalities wander about looking startlingly diminished in their prosaic humanness.

Someone takes my arm and steers me into the living room. I catch a glimpse of Barbra Streisand through the crowd around her. The crowd pans and there are introductions. She is wearing a wide-brimmed hat, a tight-fitting white dress, a shawl. I gaze at the legendary face — the mouth with its slow-curving rises and sudden soft valleys, the startling promontory of a nose, the wide and dreamy pale-blue eyes. Her slight build surprises me, as does her average height; I had thought her to be taller and somewhat more Monroe-like than she is. Until now, if I thought at all about Barbra Streisand, it was only during weary and indolent moments — watching the screen of a jet or, late at night, a television set — when her acting and singing offered me many moments of deep pleasure.

The crowd around us has gone off and we are alone. She tells me that she was at the lecture and liked it very much. We stand there talking about the lecture. Suddenly she is telling me about her father, who died when she was very young. She is recounting her recent visit to his grave in Queens, New York, and her subsequent discovery of some of his scholarly writings. I perform the novelist's trick of separating myself inside my head from an event in which I am involved and looking at it from the outside. I listen to her clipped New York inflections, observe her arm gestures, am fascinated by her mouth and faintly antic expressions. She seems a replica in fragile human dimensions of her Olympian screen presence — the charismatic ugly duckling, the Woolworth costume-jewelry clerk amid Tiffany gems. I sense in her the street-smart New Yorker, a native of my own early world, shrewd, sophisticated, vulnerable, demanding.

Somehow the talk has veered to Yentl, the movie project in which she is now engaged. She asks if I would like to see some recent location shots for Yentl after the party.

When the guests are gone, she brings me into her study, an enormous room furnished with couches, chairs, a large white desk, a white piano, a television set. A few close friends and associates are present. She finds a tape and puts it into the cassette system. The large television screen floods with color.

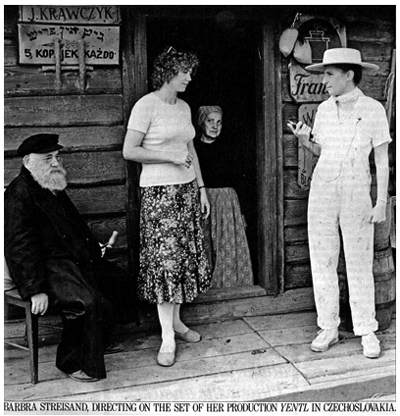

I see Barbra Streisand as Yentl walking narrow Eastern European streets in the male garb of a talmudic student. "Yentl the Yeshiva Boy," a short story by Isaac Bashevis Singer, is about a girl who loves to study Talmud. Her mother is dead, and she is raised by her scholarly father, who teaches her behind draped windows and locked doors; girls did not openly study Talmud in the ambience of Jewish Eastern Europe. After her father's death, Yentl leaves her home town, takes on the guise of a boy, assumes her dead uncle's name, and enters a talmudic academy. Intriguing adventures take place as circumstances force her into playing many roles simultaneously—daughter, man, student, friend, husband, woman—until she finally reveals her identity to the young man, Avigdor, who has become her closest friend and whose former fiancée she has married.

Barbra Streisand, approaching forty, looks convincing as Yentl the yeshiva boy, who is around sixteen in the short story but will be twenty-five or so in the movie.

Later, in the entrance hall, I tell her that I received a call from Esquire magazine about a week before, asking me to interview her.

Instantly there is a narrowing of the eyes, a taut guardedness. She pulls the shawl about her, a protective gesture. "I don't give interviews anymore," she says. Anyway, she’s too busy now with the movie to give an interview. But she'll think about it. We are standing at the door. "At least yours would be an honorable interview," she says.

Alone in my hotel room, I find myself intrigued by the encounter. I remember the location shots in which she went about in the guise of a yeshiva boy. A convincing illusion. How do you distinguish between reality and illusion in someone whose professional life is measured by expertise in dissimulation?

It is very late when I am finally able to sleep. As it turns out, it is the first of a number of late, sleepless nights that I will spend with Barbra Streisand.

ABOUT TWO MONTHS later I am in a 747 over England with my wife, whose skills as a psychiatric social worker will prove useful. We are descending through dense clouds. Wisps of mist break across the wings of the jet. The wet, orderly countryside is barely discernible below.

Early the next day the phone rings and I hear the familiar voice with the New York accent.

"When can I see you?" I ask.

She says, "I don't know. I'm up to my ass working on the script."

I let that hang in a long silence and stare out the window at the dreary London day.

It has taken weeks to arrange this trip, and now that we are here, Barbra Streisand is not certain she can see me. I wonder what the point is to that. Studied indifference? The antics of superstardom? I hold the phone to my ear and wait.

She breaks the silence. Could I come over tomorrow for a twelve-thirty lunch. She gives me her address. She isn't certain where the house is or what part of London she's living in. She thinks it's called Chelsea. She doesn't go out. On second thought, could I come over at twelve instead of twelve-thirty?

I think to myself that some sort of unspoken message has been conveyed to me in that conversation, and cannot imagine what it might be.

"I'll bring my wife along."

There is a measured pause.

"What'll she do?"

SUNDAY IS COLD, and brilliant with sunlight. A cab takes us to a two-story stone house that is painted a dazzling white. The heavy brass knocker on the door elicits no response, but my wife spots the bell and rings it. Almost immediately, a voice on the street behind us calls out, "Chaim!" We turn, and it is Streisand.

She is walking quickly toward us along the street, bareheaded, her gait springy.

"It's such a beautiful day," she calls out happily. "I've been for a walk." She comes lightly up the path to the steps. "I haven't been out of the house all week. I was beginning to feel..."

She struggles for the word.

“Entombed,” I offer.

“That’s right,” she laughs. “Entombed.”

I notice that she has no makeup on her face save the barest of eyeliner accentuating the pale-blue eyes. The three of us go into the house and climb down a flight of winding stairs to a large den. We settle into the sofas around a low table.

Barbra is wearing a long-sleeved black sweater and matching black knit pants, which are tucked into low black suede mid-heel boots lined in sheepskin and cut in the front to form a V. Around her neck she wears a long, narrow black and ecru-lace scarf, which she crosses in front of her neck and then behind, bringing the ends to rest on her chest. Her reddish brown hair is caught in a ponytail high on her head, and wisps of hair frame her face. Her long, slender fingers end in unpolished tapered nails. A large, clear simple stone adorns her left had; on her right hand is a slender silver ring with a small turquoise-colored stone.

We engage in a few minutes of inconsequential conversation in an atmosphere that feels to me somewhat strained. Barbra tells us that she never talks about herself, never has interviews. I know that she has given some interviews in the past and wonder what she is really saying. “Someday I want to write a book," she continues, “on account of these crappy books written about me. People think they know all about me. They talk about my love life and they know nothing about me, really.” She gives a faint but effectively disdainful emphasis to the word nothing. She pauses, then continues. “I can’t believe it, but legally there’s nothing we can do. I’m public property.”

“It’s so strange,” Barbra continues. “I once read a chapter in one of those books, and they got everything wrong. My favorite composer is Harold Arlen. So they wrote in that book that my favorite composer was Harold Rome. The ‘Harold’ was right. But Harold Rome was a whole other person, who never liked me and wrote an article about me saying that I was never grateful for – he wrote I Can Get It For You Wholesale. I was absolutely shocked by this article. He never even gave me the part. Arthur Laurents gave me the part.” She is talking about her role as Miss Marmelstein in Wholesale, which established her reputation on Broadway in 1962, when she was nineteen years old. "I never felt that I should be grateful. I felt that I give and they give, and we each get something out of it."

Individuals who are intensely engaged in a lengthy period of creativity rarely say or do anything that is not a reflection, consciously or unconsciously, of their focused will and compulsive need to complete their task. It occurs to me that the words "I give and they give," which seemed to have been uttered casually, might really be an allusion, calculated or otherwise, to the message I will soon receive.

I ask her how it feels to be the object of so much attention. It doesn't feel good at all, she answers. "I feel invaded. I feel that people get an impression of me that is not true. I mean, somewhere there is truth about which I'm finding out. When I was very young, they used to say I was difficult. I asked a lot of questions. I was curious in areas that didn't belong to me. Now I'm understanding people a little more." She pauses, then adds pointedly, "Especially this man-woman thing. I mean the roles we have to play as women. I never understood game playing, because I didn't have a father. I couldn't climb on someone’s knee and say, 'Daddy, I love you,' and get a new dress. It's something I've never gotten used to, playing games that way."

It is clear that there is to be no formal interview just yet and that she is unwilling or unable to talk about anything right now that is too far removed from the movie. I understand that feeling: we are an intrusion, and she will talk to us only on her own terms.

“Do you think that Yentl is playing a game?” I ask.

“No,” Barbra responds quickly. “I think she refuses to play games. She didn’t have a mother and therefore didn’t understand those aspects of a woman.”

She talks about the movie. At times it is difficult to determine where Barbra ends and Yentl begins, the edges of the two personalities blur, flow into each other. She seems filled and possessed by the work. It is a familiar sensation; novelists know it well.

Abruptly, she moves to a scene in which reference is made to two talmudic rabbis, both of whose contradictory points of view were regarded by others as acceptable. She is trying to make sense of this and wishes to use in the scene the notion that life is filled with contradictions, things can be different from one another, opposite, and at the same time good and true. Apparently, she wishes to use talmudic passages throughout the movie: in ordinary conversation, as background talk, in scenes that will depict the yeshiva at which Yentl and Avigdor are studying. I hear her say, her voice rising with eagerness, "Do you know any good things about Hillel and Shammai?"

She is asking about two of the earliest and greatest talmudic sages, men of vast learning and differing backgrounds who disagreed with each other about virtually everything. I tell her that I know a lot of things about Hillel and Shammai.

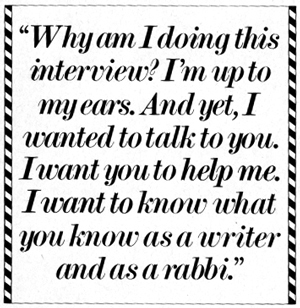

"Oh, God, could you tell me some?" Her voice is almost childlike with expectation. "I mean, if I could just get some of those things." There is a brief pause. She looks at me. "You know, it's like I thought. Why am I doing this interview? Not only because you're a good writer but because you're a rabbi. That's what I thought of this morning. You know what I'm saying? I mean, I'm up to my ears. And yet, it's really like I wanted to talk to you." She regards me keenly. "I want you to help me. I mean, I want to know what you know as a writer and as a rabbi." And before I can react, she asks me about a passage in the prayer book.

I decide to respond. My wife joins in. Soon we are on a labyrinthine voyage through texts. At one point I cite inaccurately a talmudic source and my wife corrects me. Barbra looks at her and asks, "How do you know so much, Adena?"

"She went to a yeshiva," I say. "She's a Brooklyn girl."

"Yeah? I went to yeshiva, too," says Barbra. "My first three years of school."

"Which yeshiva?" asks my wife.

“The Yeshiva of Brooklyn. In Williamsburg."

The two of them talk about their parochial schools.

The conversation reverts to the movie and the kinds of sacred texts Yentl might be studying secretly with her father. Barbra tells us that she has sought the advice of rabbis. The rabbi of a synagogue in Venice, California, refused her offer of payment for his help and, instead, asked if he could teach her son for his bar mitzvah. "I was very moved by that," Barbra says, "so that's why I support his school."

The talk turns to the subject of the status of women in Judaism. Barbra is analyzing the character of Yentl and relating it to that of the father. She stops suddenly and says, "I don't know if I ever told you the story of how I finally sat down to write Yentl after procrastinating for years and years.”

She begins to talk about her father. He was a high school teacher and held doctoral degrees in English literature and psychology. He served as superintendent of schools at Elmira Reformatory, where he taught English to prisoners. He wrote two doctoral dissertations, one a study of Shakespeare, Dante, and others, the second a study of, as Barbra puts it, "my mother's behavior toward her son." She says, describing the second dissertation, "After every chapter there's an analysis of everything that was wrong, the mixed messages my mother was giving my brother. I always had these books, but I could never look through them."

She then proceeds to relate a strange tale. "My brother is not a dreamer, he's structured right in the world, he’s not a spiritualist or anything. My brother was nine years old when my father died; I was fifteen months. So I didn’t know my father at all. My brother did. He had told me about this woman friend of his who was a medium, a nice Jewish woman, but who had this spirit that came to her when she was thirteen years old, and her mother had had it before her. He said, 'I can't tell you the experience I just had last night. I talked to Daddy.' He said, 'We put our hands on this table and the table moved its legs and started to spell out Daddy's name. Then,' he said, 'the table followed me around the room.'

"Now this is my brother. My brother's not on drugs, my brother lives on Long Island, he's doing very well. So I believe him. When I came to New York, I wanted to go visit my father's grave. My father died when he was thirty-five years old, but I had never gone to his grave. I was very angry at my father for dying, which is probably why I never read his books. Anyway, I went to see my father's grave, and I had my brother take my picture with the tombstone in back of me. On the tombstone is a Phi Beta Kappa key and the words BELOVED TEACHER AND SCHOLAR. And - you're not going to believe this but next to my father's tombstone was another tombstone. Do you know what the man's name is on that other tombstone? Anshel. Have you ever heard of anyone named Anshel? It's a rare name." (In the movie, Anshel is the name of Yentl's dead brother, the name she takes when she assumes the guise of a man.)

Barbra continues talking about her father.

Someone learned of her affiliation with the synagogue in Venice and wrote a letter to the rabbi, saying that he had once known Barbra's father. In the letter he described her father in considerable detail.

"My father was a very religious man," Barbra says. "He worked for his parents, who owned a fish store in Brooklyn. He went to New York University and to Columbia Teachers College, and one Friday afternoon he couldn't get home before sundown and he walked back to Brooklyn; he wouldn't ride on the Sabbath. His dream was always to go to California. He wanted to be a writer. The author of the letter sent Barbra a picture of her father. "I look just like my father," Barbra continues. "I'm built like my father. I said to my mother, "Why didn't you ever tell me about my father?' She said, 'I didn't want you to get upset. I didn't want you to miss him.' So I never heard about my father. And now it's like, I find pictures of his college things — he was on the debating team, he was interested in drama, he was a member of the chess club. To earn money, he was a lifeguard. "He was a strange combination — tennis, swimming, Talmud, fencing, mathematics club. In fact, I find that I'm like my father and I never knew it. I feel like I put on my father's clothes and became my father." Her voice is controlled but resonant with what I sense is real emotion. She continues her story, and now the words take a bizarre turn. "I went back that night after the cemetery and I said I wanted that medium to come. She came over and we all sat around and put our hands on this table. The table starts to move a little. I'm very suspicious. I thought it was electrical energy that was moving the table. The legs started to move a little bit. I started to get very scared. I remember I got up and went to the bathroom. When I came back the table spelled out my name. It spells out the letters, like one-two is B, one is A, and R is one-two- three-four-five-six... way down. I was so scared. It was just awful. It spelled out S-0-R-R-Y. And it spelled out S-I-N-G. Then it spelled out P-R-0-U-D. Then the table stopped moving."

I have always regarded spiritualism as charlatanry. Yet, listening to her, I have the distinct feeling that she is reporting this illusion as a real event that somehow conveyed to her and her brother messages of truth that they both needed to hear. I did not know at the time what to make of her story — and still do not to this day.

During the flight back home, she read her father's dissertations. He began to exist for her, he became real. "I think it has a lot to do with Yentl," she says earnestly. "I want to dedicate this film to my father."

OVER LUNCH THAT day we talk about man-woman relations in Jewish Orthodoxy. My wife says that much of what passes as religious law in this connection is really not law at all but a powerful sociological orientation. Barbra picks this up immediately. "That's what I'm saying. It's not law. It's bullshit. Men have used these things to put women in their place."

"Right," says my wife fervently.

"The Church did the same thing," Barbra goes on. "It's that same struggle we're coming back to, this male-female power struggle. I think it also has to do with erections. A man is so capable of feeling impotent that what makes him able to have an erection a lot of the time is the weakness of women, feeling stronger than the woman. What would happen to a society where the women are just as strong as the men? Would there be babies?"

Later that afternoon, she asks if we would like to hear some of the music from Yentl. In the den, she puts a cassette into the tape deck of the stereo. Suddenly the air vibrates to the haunting sounds of a dulcimer. The room swells with the slightly nasal Streisand voice, its two-octave tessitura richly textured at both ends of the range, now low and soft and breathy, now powerful, now surging. I note how carefully she pronounces her words, the syllables distinct. Her singing and speaking languages are quite different from each other.

The music ends. Then, in response to a question I put to her, she says, "I'm absolutely terrified about being a director. Everybody is talking to me. I have no moment alone. Everybody has to know the answers to everything. I'm getting paid back for all the times I thought I knew the answers. I feel like I'm in prison, like I'm sent away to Siberia and I have to do my time. What I'm trying to figure out is how to get joy out of work. If I record, that's a good thing, because it's controllable somehow.

"Movies are design," she adds. "Movies are graphics. I love designing houses; I have seven of them." We have been talking for about six hours and I finally say that I think I will let her rest.

"I'm gonna work now," she announces. Then she says that she would like to see us again. Would I read the new version of the script? She'll have a copy sent over to the hotel.

It is night. Her girl Friday phones for a cab.

Inside the cab, my wife says, "I think that under all the hype is someone who really wants to know the world she's portraying."

"Did you get the message?" I ask.

"Yes."

The message is clear; I give Barbra some days of work on the script; she gives me the interview. Yet, intriguingly, the bait is less the interview itself than it is the world she is trying to portray, my feeling that I ought to help her avoid crude errors, my awareness of the potential quality of the material and its possibility for art. I am disturbed by the I-use-you, you-use-me relationship that she has established between us but, at the same time, am pleased to be able to participate in the film. And I sense that she assumed I would feel this way.

THE NEXT EVENING we are back in the den with Barbra. With us are Alan and Marilyn Bergman, the lyricists who wrote the words for the songs in Yentl. The five of us sit in that den for hours, discussing dialogue and scenes, much of the talk centering on the Jewish content of the film — this talmudic idea here, that folkloristic notion there — avoiding any attempt to romanticize the tradition and bearing in mind that the movie must speak to all sorts of people.

It becomes clear to me in the course of the evening that in most matters Jewish, Barbra's knowledge is confused and rudimentary. Yet she asks questions openly, unselfconsciously, with no hint of embarrassment, and takes notes with the assiduous concentration of one long committed to learning. I have no way of gauging the depth of her comprehension. Her mind leaps restlessly, impatiently, from one subject to another: she wishes to know everything, and quickly. At those moments when a good idea comes suddenly to life from one or another of us, I see on her lips an amazed smile, a near-sensuous delight, and her eyes flash.

Hours later, my wife and I are in the front hall, putting on our coats. It is close to midnight. Barbra, standing beside me, murmurs, "I'm not taking advantage of you, am I, Chaim?"

She says this seriously and with no attempt to charm, and I answer that if I felt she were taking advantage of me, I would certainly tell her so.

"I am taking advantage of you," she says. And adds, "But we're both really trying to do the same thing."

We are at the front door. There will be a script conference tomorrow with some people from United Artists and the Bergmans, she says. She'll call us.

The next day, seated in chairs and couches around a large, low table that is cluttered with pads, scripts, coffee cups, cassettes, and tape recorders, we begin to talk about the latest script of Yentl. The talk turns to the value system of the turn-of-the-century world in which the movie is set, to the possibility of having the relationship between Yentl and Avigdor consummated sexually. I feel like a character in a bad novel.

Everything seems askew, dreamlike, absurdly riddled with the vacuousness of commercial Hollywood illusion and the clichés of forgotten books and movies.

The next night there is another script conference. My wife and I have spent the entire day working on the script, augmenting the character of Avigdor and writing a first draft for a new ending. The script was studded with awkward errors — about Jewish rituals, biblical passages, and other such — and we corrected them.

The night wears on. Hours later, Barbra is reading aloud our version of the ending. It seems to me a flippant reading, words skipped and blurred, passages intoned mechanically as if from a telephone book. She appears unimpressed and unmoved. I am annoyed by her manner of reading. I listen to her and have no notion of what she will do with our suggestions; we will find out when we see the movie. Well, I tell myself, I gave and soon she will give. An equitable arrangement.

SOMETIME LATER, I am alone with Barbra in the den. The low table is awash with cups, saucers, scripts, cassettes. Barbra has on tight-fitting olive-green leggings and a matching knitted, olive-green, long-sleeved tunic that extends to her thighs. Hanging from a leather thong around her neck is an olive-green lavaliere. Unlike the bright white hues of the clothes she wore on the night we met in her Los Angeles home, her garb all this week has seemed to favor earth tones. Like Yentl the yeshiva boy?

"Interview at one o'clock in the morning," she says now and gives a nervous little laugh.

We are entering the structured geography of the interview relationship, which she cannot easily control. The air between us, relaxed and informal all through the many script conferences, has become subtly charged.

I begin by asking her this question: "In terms of your art, where do you place yourself? Do you see yourself as a singer, an actress, a fusion of both?"

She tells me that she has always seen herself as an actress and thought that to be a singer was demeaning. The words are followed by a ripple of laughter. "Isn't it awful? It sounds terrible. Even when I was about five or six, I remember singing in the hallways of my apartment in Williamsburg on Pulaski Street, because it made a wonderful sound in the hall. And when I was about nine, neighbors and I used to sit on the stoop together and sing harmonies. I was known as the girl with the good voice. So my mother took me to an audition for MGM. My mother wanted to be a singer, but she was too shy. My mother has a beautiful voice, a very high, light soprano voice. I remember what I wore, too. A blue dress from Abraham and Straus, with white collar and cuffs. I had to sing behind a glass booth. I sang a song, and the guy said thank you, and that was it."

At the age of fourteen she entered acting school. She would go to the Forty-second Street library and look up all the parts that were played by Eleonora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt. In the film library of one museum she saw a movie Duse made in 1916. "She was incredible to me, very real. So singing to me wasn't a — I wasn't a singer. I never wanted to be a singer."

She began to make the usual rounds as an actress, but that lasted only two days. "People could use their power over me. They had power to treat me like an animal. I had no dignity. I gave up. I just found it so demeaning to say, "Do you have a job for me?' I couldn't do it. Two days. That was it. I gave up my career. I thought I'd design clothes or something. One day a friend of mine said to me, 'There's a talent contest where you get free meals' — which always interested me. I listened to some songs and I learned one of them, and I entered the talent contest and I won. But when I was singing I always felt, This is not who I am, I'm not a singer, I'm an actress."

Someone from the Bon Soir club was present at the talent contest and asked her to come over to the club and audition in front of an audience. She got her first job.

She is talking softly and evenly, smiling at this or that summoned recollection. She remembers taking classes at the Actors' Studio with Lee Strasberg, who never paid attention to her. "I was nobody then," she says. Years later he came to see her in Funny Girl and she said to him, "Lee, I don't know what it is. You teach preparation. You know, the actor prepares. I can't prepare. I have to sort of walk on." And he said, "Your preparation is not to prepare. It's okay." She has to be thrown into the environment she says, "and then I can deal with the reality. But I can't prepare for the reality. I like to work moment to moment. It's the only way I know how."

She stops. Then, in a seemingly offhand manner and disconnected fashion, she says something quite profound. "When I was fifteen, I remember seeing things like — most people, even if they were nothing much — I mean, no charisma, no particular aura — if they pretended to be something they were not, they were nothing. But if they just were themselves, if they were just being, they were fascinating, just by being human. Once they acted, it was false. They were their inadequacies. But once they were just nothing, they were something."

It turns out, surprisingly, that she feels herself separated from normal society as well as from the society of which one expects her to be a part. "I never felt part of the world," she says hesitantly. "I mean, I always felt like some sort of outcast. I'm not comfortable with my success. I never was. I don't like to be recognized. I don't know that I'm like a famous person or star. I feel just like a workaholic. Sometimes when I was around people like Sophia Loren or Elizabeth Taylor, they were like stars to me. They acted in a certain kind of way, you know? Like you see in the movies. They're very comfortable with the press, with photographers. You see pictures in the paper of Jackie Onassis or Elizabeth Taylor. They're always smiling like ladies. You see pictures of me, it's like, you know, leave me alone, get outta here, why are you taking my picture? Don't you have any respect? They click flashbulbs in people's faces and you can't see anything. It's not polite. It's not kind. I resent being treated like a thing, a commodity, an image. I don't think I'll ever get used to it."

She wants to be famous and anonymous simultaneously. A wish for irreconcilable opposites: unlimited candy and perfect health; endless blue skies and rain-rich valleys; parents forever present and care-free independence. Hillel and Shammai in eternal harmony. I am on familiar terms with that wish.

"You don't see yourself as part of organized society?" I ask again.

"I'm not saying I'm right," she answers. "I'm certainly not particularly comfortable in the world. At this point I live in this cocoon, so I don't even know what the world is."

A pause, a deep breath. The eyes have narrowed, are reflective. She has started to feel very Jewish, she says, and resents the present apparent rise of anti-Semitism. But she is not the kind of person who goes easily to the barricades. "I'm more frightened than most people are. I mean, I want to become more that kind of person, go to the barricades, fight back, and do what I can to change things. But sometimes I think — this is going to sound terrible, very pessimistic — but I do believe that the world is coming to an end. I just feel that technology, science, and the mind have surpassed the soul, the heart. There's no balance in terms of feeling and love for fellow man. Yet I thought it was important to sing against the Moral Majority."

I remember the troubled talk about the Moral Majority in her Los Angeles home and sense in her a dread of looming repression. Ancient tribal antennae raised toward distant winds of persecution. We return to Yentl. She can already feel the attacks mounting against her, she says, because she is producing, directing, starring. "Some of the things I've done I'm not proud of. I've done movies at times for the wrong reasons. I want to return to the dreams I never fulfilled. I mean, I really want to do Shakespeare and Chekhov and Ibsen, parts that I've always wanted to play and said I would play but have never gotten around to. I'm tired of saying, 'I could have done this.' I want to do it. Because life is growing short. Maybe because my father was so young when he died, I seem to have I a drive to get it all in. I want to take chances now. I mean, I want to risk the failure. I want to put my money where my mouth is. I so respect directors and their obligations and responsibilities. It's an incredible challenge."

Even more so is the challenge of being a producer. Streisand seems nearly overwhelmed by her financial responsibilities; by her dealings with the unions and with insurance companies; and by the casting process. And she seems obsessive about the problems of production design, makeup, costumes, hair, and every piece of cloth. "Every color is important," she says. "I have to deal with sketch artists, musical numbers. What's awful is that everybody gets to get out of here and I can't leave. My boyfriend goes home, my son goes home."

Yet, in a city rich with theater, she allows herself no diversions.

"I don't like going to the theater," she says. "That sounds awful. That's why I hate being interviewed: 'I don't go anywhere. I don't do anything.' I like to go to the opera and the ballet. I go to the theater and most of the time I don't like what I see. People look at me. I get claustrophobia in theaters. I feel like I have to get out I have to sit on the aisle." She says that she hated her early experience in the theater. "I liked the rehearsals. I loved changing scenes, changing things, songs, every night, change. But once they freeze it, that's it, you're in prison. That's why I like movies. You do it, it's over; you do it, it's over. You don't have to keep doing the same thing over and over again."

Comfort in a kaleidoscope. Why? Too many painful memories of early fixed reality? Therefore the need for the world of change and illusion? Perhaps in this she is quintessentially American: kinetic, restless, endlessly searching for new frontiers. I ask her if she's finding anything in religion at present that she didn't find there before. "Are you returning to it in a serious way?"

She says that she never left it. "I'm a Jewess through and through, although I'm not religious. I don't do anything intentionally to hurt anyone. I feel like I'm a good person. And that feels very Jewish to me. There isn't enough support for Jewish artists and Jewish culture, so I'd like to support that. But I don't go to shul on the Sabbath. I'm not a born-again Jew."

"You feel a loyalty to the Jewish people."

"Yeah. I'm proud that I'm a Jew. I mean, I always like it when I light the Shabbos candles, but I don't do it every Friday night."

"Barbra, what question would you have liked me to ask you that I didn't ask you?"

She seems surprised by that and is silent awhile. I hear her murmur, "Oh, God, I don't know."

Then, as if a signal has sounded a warning inside her that she has been separated too long from her current obsession, she returns to the subject of the movie and the tribulations she has had to endure in order to get the movie made. She seems fascinated by these tribulations. "It's interesting how all the obstacles have been put up to Yentl. I mean, even the war in Poland was an obstacle. Czechoslovakia, the border, the government. The studios not wanting to make it, putting me through the wringer."

I ask, "How'd you finally prevail?"

"I just wouldn't give up. I mean, I had to do it. The more obstacles I had, the more I had to do it. Do you think I'm crazy to, like, to ask you to give me a hand, to write, and things like that? Do you think that's terrible to do?"

She did not have to ask me that I sense genuine feeling in her words and tell her that it is not a terrible thing, that most creative people would like to do all their work alone, by themselves, but sooner or later find that they need the help of others in order to realize their own mysterious and bewildering drives. Sometimes when creative people come together, they establish their relationship — whether they're aware of it or not — on an I-use-you-with-dignity, you-use-me-with-dignity kind of basis.

She takes this in, her face expressionless, her eyes wide and staring, and does not respond.

I say quietly after a moment, "I wish you a lot of luck, Barbra, and a lot of patience."

She says, "Yeah, one of my biggest faults is my need for instant gratification. I don't have much patience. But what is there in life but to devote yourself to something you believe in? I mean, what would I be doing if I weren't doing this? Lying in the sun in Malibu? Making a movie from a silly script? As I get older I find it more difficult to get dressed in the morning, put on makeup, act. In order to make this movie, I had to give up all my so-called power."

I ask, "What power have you given up?"

"Everything," she says. "They could take the movie away from me at any time."

"'They' being?"

"The studio."

"I thought you owned the property. You sold it to them for their participation in production costs?"

"They finance the movie. They give me fourteen million dollars. They have script approval. But they approved the script that was back when. They can stop me from hiring certain actors. And that's odd for me, because I've always controlled my work, down to the negatives and the printing and the lettering on the covers of my albums. I get involved with all that."

"Who has the say on the final cut?"

"UA." This is said almost inaudibly. It is a stunning admission, for it means that United Artists has control over the final version of the film and can edit it to its own tastes.

"Why'd you do it, Barbra?" She had no choice, she said. She did not want to risk her own money. "I had to eat shit, put it that way. You know what I mean? You want to do it, this is the way you get to do it"

I am curious about the technical problems involved in being both actor and director at the same time, and she describes how she will structure scenes, the part played by the understudy as she, Barbra, moves from set to camera and back, and the responsibilities of the camera operator. It seems to me enormously complex and tedious work, this repeated changing of roles.

"Look," she says abruptly. "It's crazy. But Warren Beatty did it in Reds. And Woody Alien does it. But he makes small pictures, usually contemporary. They're funny comedies. Charlie Chaplin did it. And Orson Welles. I don't know. Mine might turn out to be a complete failure, a fiasco, humiliating, a terrible thing." She looks at me and smiles dazzlingly. "It's such an interesting gamble, isn't it? I mean, it's like shooting craps." In this game of craps, Barbra has dearly isolated herself in an elite club of legendary moviemakers.

It is after two in the morning. She seems indefatigable. The interview is drawing to a close, as is my week with Yentl in London.

ALL THROUGH THE journey home and in the days that follow, her face and voice linger in memory and I find that I miss her presence. A certain ineluctable quality of charismatic radiance has brushed against me, and I carry it on a speaking trip to Los Angeles soon after my return. There I talk about her with a number of people.

Those who know her professionally tell me of her prodigious talent, her fits of impatience, her toughness and tenacity, her relentless striving for perfection. Some bemoan her personal life; others say it is no one's concern but her own. A producer tells me of phone calls made by her in an effort to patch up real or imagined hurts. A rabbi tells me of her benevolence to institutions of learning, her honest interest in matters of the mind. A director reaffirms my sense of her basic integrity. In a field not overly sown with seeds of human virtue, she seems something of an unusual and quixotic flower.

As the resonance of the London journey fades, the welcome perspectives of time and distance enable me to attempt some suppositions about her. She seems to me to be among those creative individuals who find it necessary to construct elaborate stratagems of abnegation that often border on self-torture. This intensifies their misery and thereby, in mysterious fashion, heightens their art. I sense about her something of the aura of the narcissistic personality: alluring, playing at being charming, centered on one's own self, laboring relentlessly and expecting the same of others, too soon bored with achievement, too quickly disdainful of permanence, grasping at opposites, at times impatient to near ruthlessness with those of smaller mind or lesser vision. This is meliorated somewhat by her self-effacement, her recently reinforced sense of Jewishness, and her awareness that if you pretend to be something you are not, you are nothing.

I think, too, that by fusing her identity with that of Yentl, she is recovering her long-lost father and his religious tradition. She is extending his life and his Jewishness, thereby assuaging a deep sense of guilt at having already lived longer than he. Also, through that extension she is reliving her own childhood as if her father had not died and abandoned her.

It seems clear enough to me that while the movie enables her to continue her father's life and Jewishness through the power of illusion, it gives her at the same time the opportunity to assert forcefully her own creative individuality in the real world. As if in confirmation of this, a cable arrives from her some days after our return from London.

The cable reads:

DEAR CHAIM

SOMEONE ELSE'S WORDS BUT MY REASON FOR DOING "YENTL." "IF I DO NOT ROUSE MY SOUL TO HIGHER THINGS, WHO WILL ROUSE IT?" MAIMONIDES. BEST WISHES BARBRA.

END

Related Pages: Yentl movie page

Scavullo Cover Photo Outtake