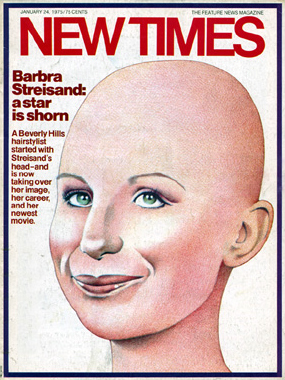

New Times Magazine

January 24, 1975

Collision on Rainbow Road

By Marie Brenner

When Barbra Streisand, a multinational showbiz corporation, had a wig cut by Jon Peters, a Beverly Hills hairdresser, love blossomed. So did Peters, who took over Barbra's life and then took over her next film, Rainbow Road, a $5 million remake of A Star is Born that has become Hollywood's biggest joke

It's an early November morning in Beverly Hills and hairdresser Jon Peters is on the phone with Hollywood powerhouse agent Sue Mengers. "Yeah, uh, uh huh . . . that's all you can get?" Peters asks. He stares at himself in the full-length mirror, oblivious to the scene around him: women in smocks having their hair washed, blown out, curled and frosted.

"OK, OK, OK." Peters, a self-styled "street-fighter," is, for once, listening. Behind him three assistants are standing over a hair-frost process, waiting for their teacher's return. A minute ago, Valerie Perrine wandered through the door without an appointment and upset the morning's schedule. But these are minor problems, and this phone call is business.

So Jon Peters is tugging at his black hair, checking himself out in the silvery mirror by the reception desk. Today he's got on the brown and gold checked sweater, platform saddle shoes and hip-hugging corduroys without underwear. He half turns to see if his extra ten pounds of newly acquired movie mogul girth show. And all the while, he's listening to Sue Mengers. Because this morning he has more on his mind than the streaked blond who worries about getting it on with her gardener (his advice to her: "Go ahead, break out, forget the old-fashioned ways"). For ten years, he's cut hair and put up with the tsouris of Bel-Air housewives and Hollywood stars, but now he's taking his own advice and doing a little break-out himself.

Not so little, really. At 30, the chunky half-Italian, half-Cherokee has risen from no status as "a kid with dirty underwear going to beauty school" to hair stylist, to husband to actress Leslie Ann Warren (Mission Impossible), to shop-owner, to hair stylist for Barbra Streisand, to boyfriend of Barbra Streisand, to roommate of Barbra Streisand, to record producer for Streisand's new album, Butterfly, to Streisand's movie producer. Only the big plum is left - and Sue Mengers is delivering it by phone to the Emperor of Hair on Rodeo Drive: Peters, already the producer of Streisand's and First Artists-Warner Brothers' $5 million musical for 1975, the fourth version of A Star is Born, is to become the director as well.

And as new director Jon Peters will later say, "The whole world is waiting to see Barbra's and my story." And with filming starting this spring, the whole world is going to have its chance soon enough.

The only problem for Jon and Barbra was convincing Warner Brothers to let them have their fun.

Fall, 1973

John Dunne and Joan Didion have an idea. Why not write a movie about two rock singers, one on the way up, one on the way down? Make it a love story, make it a tragedy. So, being real writers, they call up their ex-agent, Dick Shepherd, now head of production at Warner Brothers. "What a good idea," Shepherd says. "I wonder why we didn't think of it."

It just so happens that the Warner Brothers library holds the three original versions of A Star is Born. Shepherd suggests a remake; it will be easier to convince Warners to do the project that way. The Dunnes have never seen A Star is Born, not even the Judy Garland version, not even on TV. Anyway, it's the rock world that interests them. They've been traveling around with Jethro Tull and Uriah Heep, cruising the late-night concert scene, lapping up the details of the Glitter City underbelly. "Warners wanted us to see the movie," Dunne said later. "But we assiduously refused to do it. We knew what it was about."

John Foreman is to be the producer. In the 1960s he produced many of the Paul Newman blockbusters. After Serpico became a hit, he decided to make a film about David Durk, Serpico's Ivy League partner. Foreman worked for weeks on the project, getting releases from everyone involved. He forgot to get one from David Durk. That movie never got made.

But now Foreman and the Dunnes are working together on their rock-umentary, loosely based on A Star is Born. A first draft screenplay is completed. They submit it to Sue Mengers of Creative Management Associates, hoping she'll shuttle it along to her clients Peter' Bogdanovich and Cybill Shepherd, who'd make the project a "salable package" for the studios. "I thought it was awful," Bogdanovich says. "But I showed it to Cybill. She likes to sing. I thought she might like it. She didn't like it much either."

Along comes Mark Rydell, sometime actor (The Long Goodbye) and the kinetic director of The Cowboys and Cinderella Liberty. He loves the material, calls it "a savage look at the rock world." He loves the Dunnes, calls them "frighteningly brilliant." But Warners offers him squat for his services. So he agrees to develop the project for free; he's given 90 days to punch up the first draft, cast the film, and get some of those spectacular concert scenes off the drawing board. If he can do all this, he gets to direct the film. For good money. "My agents thought it would work out," he'll explain later.

Somewhere in the deep background, Jon Peters is making space in his closet for Barbra Streisand's clothes. Until he was hired to cut the wig she wore in For Pete's Sake, Barbra was sitting home nights, watching TV and playing with her son, Jason. The temperamental Streisand had gone through every hairdresser around when Peters was called in on an emergency basis. "She kept me waiting an hour and a half," Peters will recall. "I said, don't you ever do that again." Barbra liked that: a man who took charge of things. A change from the yes-men and ego-massagers who only fueled every neurosis. So now she's moving in.

April, 1974

Moving into the foreground now,Jon Peters is working with Barbra Streisand recording her Butterfly album. It is something of a departure from the standard Streisand fare. Jon Peters has decided there is a problem with Barbra's image: dowdiness. She needs to open up, free herself. With a shot of rhythm and blues. Barbra has been playing "Ray Stark's mother-in-law" for too long. Time she started to groove - with reggae, David Bowie and "Let the Good Times Roll." And Jon as the producer. Beautiful. Even Columbia Records thinks so. It's just that they're having some problems getting their vision on tape.

Meanwhile over at the Rainbow Road offices - that's what they're calling A Star is Born now - Rydell and the Dunnes are having trouble finding a cast. Richard Perry, the music producer, is brought in to help out. "Rydell wanted it to be a total collaboration," Perry will recall. "I suggested everybody from Minnelli to Elvis." Casting is not the only problem, though. Perry doesn't like the script: "It really didn't catch the contemporary rock-pop milieu. Everything in it was cliched. That's when I got misgivings."

An increasingly frantic Rydell pushes for Carly Simon and James Taylor. They demur, saying it's "too close to their relationship." Rydell pushes next for Diana Ross and Alan Price (Oh, Lucky Man) but Motown's Berry Gordy, who controls Diana Ross, turns him down cold. And Warners considers Alan Price "too esoteric." Warners wants its own record stars in the film so that the soundtrack album will clean up for the parent corporation.

Rydell is running out of time and everyone - Warner Brothers, the Dunnes, John Foreman - is hocking him to "get it on" (Hollywood jargon for making the project happen, already). They settle on Kris Kristofferson for the male lead. But a female star cannot be found and the cameras are supposed to start rolling in September; Warner Brothers is short on product for 1975. Rainbow Road could be a '75 Christmas biggie. If only there were a female lead. Forget the fact that there are 20 songs to write, approve, arrange and stage. And a screenplay still needing a rewrite. And complicated concerts to plan. Warners wants those cameras rolling. It still hasn't occurred to anyone that the first three versions of A Star is Born never made a dime.

May, 1974

Jon Peters and Barbra Streisand are working on the modeling of Peters' ranch house in Malibu. Butterfly has been salvaged by calling in Kathy Kasper, the music contractor. Peters has agreed to give her a major credit for bringing in several new songs and rescoring some of the unusable cuts.

And in the studio, veteran engineer Al Schmitt has been brought in by Columbia to remix the album. "Schmitt did three cuts," Barbra says. "I didn't like them." Schmitt goes off the project. But the Columbia executives are happy with the album now; they think "it's not only one of the best, but one of the biggest albums Barbra's ever made." They plan to have Barbra close the August sales convention singing tunes from Butterfly.

The album is, finally, manufactured. On the credits, Kathy Kasper's name is nowhere to be found. "It must have been an oversight," Jon Peters will say. Her name will definitely appear on all subsequent pressings.

Summer, 1974

Mark Rydell is on the phone with his agent. The 90 days of his "free development deal" are over. Warner Brothers will not "go forward" with him on Rainbow Road. Rydell says, "The Dunnes and John Foreman thought I was dragging my heels on the casting. There were a number of people they thought would be good, and if I had said yes, they would have gone ahead with some of their in-house record stars." But he wouldn't, and they didn't, and now Rydell's lawyer is having a tough time collecting the $147 Rydell laid out for research materials and commissary lunches. Warners isn't making a "courtesy payment" for three months of Rydell's time. In fact, it will take him two months to collect the $147.

But at least the second draft is finished. Warners finds it vastly improved, a gritty hard-core look at the seamier side of rock. There is, however, no tight relationship between the male and female stars. And while Kristofferson has committed himself to the project, he has not formally signed.

Warners now calls director Jerry Schatzberg, whose epigrammatic, often downbeat Scarecrow won the Cannes Film Festival for them. A gritty take on the rock world by the Dunnes appeals to him (he'd worked with them before, on Panic in Needle Park) and he signs a development deal.

At which point Sue Mengers sends the script to client Barbra Streisand.

"I discovered this project," Jon Peters will later say. "I was the one who found it for Barbra and convinced her to do it." He has, he believes, rescued Barbra from her identity crisis; she will be happy to show her fans a "newer, softer Barbra" in a rock and roll movie. Already, she is living more like a rock person now that she's left Bel-Air for Jon's funky Malibu ranch. Her hair flows down her back these days. She plants orchids. And plays with the $25,000 sound system - the hidden jukebox - Peters has thoughtfully stocked with the Streisand Sound.

She is also seeing the same gestalt therapist who treats Jon Peters and Leslie Ann Warren. In fact, they are all very close. Because Peters is trying "to open myself up." He is fascinated "by negative feedback," fascinated by his relationship with Barbra and mostly, of course, fascinated with himself. "I'm a fella who, when I was nine years old, watched my father die in front of me," Peters says. "So I know about death. The character in my movie is a guy who's fighting all the time and hitting all the time. And he can't relate. It's the macho story, which is very much me."

The "macho" who runs the two beauty salons - in Beverly Hills and Encino - started young. His mother is related to the Paganos, well-known L.A. beauty salon owners. When his father died, Jon became a disciplinary problem. He dropped out of school in the eighth grade, was sent to "training school," ran away to Europe and got married at 15. He split from that wife, returned to Los Angeles and started hanging around, watching Gene Shacov - the freewheeling, cut 'em and lay 'em character who was the inspiration for the hairdresser played by Warren Beatty in the upcoming Shampoo - work on the heads of the rich and powerful. Peters learned his lessons well. By 21, he had met and married Leslie Ann Warren and chopped her hair off. A year later, Blow Up was released; hairdressers were in and Peters opened his own shop. A few years go by. Jon and Leslie Ann split and Jon installed his mother as the receptionist at the Beverly Hills shop.

So isn't this the perfect time for Sue Mengers to give Barbra a script about two singers, "trapped by their money and success, trying to relate to each other and really get into their feelings," as Peters synopsizes it. He'd like to change it a little, though.

"Two people fall in love," Peters explains. "She becomes a super superstar by realizing what the most important thing to both of them is: communicating. Wanting to have children. Not the thousands of agents and press agents and all that stuff that control their life. He's a guy who spent the first 30 years of his life fighting - very aggressive - and then met this woman and fell very much in love and realized that this was his chance to live. But he accidentally dies. For us, the understanding of it - through film - is a very heavy thing. Do you know what I mean? That's why the script has to be perfect. Because it has to be right for us."

But Schatzberg, the Dunnes and John Foreman are not keen on making a $5 million home musical, Barbra and Jon, out of their gritty rock story. Not that their opinion means anything - Barbra Streisand, they're made to understand, is interested in starring in Rainbow Road. And as her very next project. This is no minor announcement; with the return of the star system, Barbra Streisand is more than just an actress, she is a multinational corporation, the only female star whose whims areas powerful as the edicts of the studio chieftains. In her 12-year film career, she has made $ 12 million-for herself. Her last film, For Pete's Sake, was an embarrassment to all concerned, but it brought the money men $9 million. So when Barbra Streisand decides to make a movie, and a musical at that, there are smiles in the corporate offices. Which is why no one at Warners fights with her about making Jon Peters the producer of Rainbow Road.

"Anyone who wonders how a first-time producer can do it," rationalizes Peters, "just has to take a look at the way I produced Barbra's album. Or how I run my beauty salons. I employ 300 people. I'm a businessman, man, that's all." As a businessman, all he has to do to attach himself to Rainbow Road is move into an office and keep his mouth shut, leaving the big decisions to the Dunnes, Foreman, Schatzberg, Kristofferson and Warners. He does not do this.

"We loved each other at our first meeting," Schatzberg remembers. "I went out to his ranch; he showed me where he was putting old wood everywhere, the outdoor Jacuzzi... we had a good meeting. I didn't see any books, but... I went back to New York with the idea that we were going ahead with the project."

Schatzberg and his wife return in July. A big basket of fruit from Barbra and Jon is waiting at the Beverly Hills Hotel. But the Dunnes are worried now; if Barbra agrees to star in the movie, the project will leave Warner Brothers and become the property of First Artists.*

[* First Artists is a subsidiary of Warner Brothers, a company controlled by the "artists"— Dustin Hoffman, Paul Newman, Sidney Poitier, Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand. In return for making three pictures without the million-dollar "front money" that any other studio would have to pay them, the stars can make whatever movies they want, so long as the budget is under $3 million for a dramatic film, $5 million for a musical. Warners gets the distribution rights, reimbursing First Artists for two-thirds of the film's negative cost upon delivery of a finished film. And the artists get 25 percent of the gross - a quarter for every dollar the theater owners return to Warners - right off the top. They aren't, therefore, encouraged to make small, personal, non-commercial films. Even so, no First Artists star has made a vanity production for the company. This may not be the case when Rainbow Road starts shooting in the spring. ]

Nevertheless, they agree to dovetail the project for Barbra. But although the Dunnes and the Streisand-Peters all live in Malibu, the Dunnes will not meet with Jon - even for a little story conference - until they have completed the new draft. The Dunnes say they work best alone.

Barbra, meanwhile, is squabbling with Kristofferson about billing. She refuses to see his name above the title with hers. Kristofferson's lawyer, therefore, is holding up the negotiations. Jon Peters is beginning to feel left out. Schatzberg gets a call from Barbra. She wonders what Schatzberg thinks of Jon playing the male lead. Schatzberg thinks she is kidding.

A hasty meeting is called to discuss this at the ranch. Jon and Barbra keep saying that Jon can play the part better, that the world is waiting to see them together. "I don't want to shoot a documentary about you two," Schatzberg says. John Foreman, now leveraged into the relative Siberia of executive producership, is silent. Then he reminds Barbra that if the project does go over to First Artists, Kristofferson is still attached to it. Barbra is angry. "You mean Warners would really rather have him than me?" she demands. "Can Peters sing?" Schatzberg asks. It is the key question. "No," Jon Peters admits, "but you said you could shoot around me. Like you're going to do with Kristofferson." A weary Schatzberg: "Look, you can do that with a singer to make it look like his acting has more energy. You can't do it with an actor to make it look like he's a singer." The meeting is over. Jon Peters, the haircutter turned record producer turned movie producer, will not make his debut as an actor.

Rainbow Road now seems to be under way. There are fights over production managers, over the music people, but the project is, sort of, moving ahead. Jon Peters settles into his new office at Barwood, Barbra's company within First Artists, and orders a stereo just like Schatzberg's. The Dunnes are still hung up about the relationship between the male and female leads, but Schatzberg isn't worried. "Screenplays take a lot of work," he says.

Barbra still hasn't signed though. Nor has Kristofferson. And Warners has not turned the project over to First Artists. What does happen is that Dick Shepherd-the Warner Brothers executive holding the project together-leaves the studio under pressure. Then Ted Ashley, Warner Brothers' president, resigns. The film is now in a curious limbo. And while Barbra finishes Funny Lady, Jon Peters cuts hair every Wednesday and Saturday in Beverly Hills.

August, 1974

The Dunnes submit their third-draft screenplay. "The third draft was little more than a rehash of the second draft," John Dunne recalls. "It's tough to tailor a part for a star. We were all played out at that point." But as much as the Dunnes want out, Jon Peters wants them out even more. Warner Brothers agrees. The Dunnes are given $125,000 plus 10 percent of the gross. "We came out smelling like a rose," John Dunne says. "I really hope the movie gets made, we have such a nice chunk of it. And I'm sure relieved to be out of it."

Jon Peters now has an idea. Or rather, he has a friend with an idea: Jonathan Axelrod, stepson of screenwriter George Axelrod and, just coincidentally, a CMA client. Sue Mengers has given him the Dunnes' script. Why not reverse the roles, Axelrod suggests; let Barbra play the Norman Maine character, the star on the way down, and Kristofferson can be Esther Blodgett, the protege whose career outstrips her sponsor's. Peters thinks this is brilliant. He does not know that over the past 40 years three other directors have had the same thought - William Wellman, George Cukor, Mike Nichols - and they have all rejected it.

"My original idea was to reverse the roles, make her like Janis Joplin," Axelrod says. Schatzberg disagrees. Peters and Schatzberg begin to part company. They see less of each other. Barbra and Jon are seen going into a restaurant at the beach. Jon says, "I've been trying to get into this place for eight years. I'll get in tonight." The maitre d' seats them right away. The restaurant is half empty.

Now the heat is on. Peters insists that the script be turned over to him, that he develop the movie along Axelrod's idea. He tells this to John Calley, new president of Warner Brothers; Warners still owns those rights to A Star is Born. Calley recalls, "I'd never met Peters before. He came in and said that in his and Barbra's view, the screenplay was moving away from being suitable for Barbra. I agreed with them. Forget about whether the screenplay was good or not, the issue was 'is it right for Barbra?' He said, in effect, 'It's very simple, either we get to take over the screenplay and make it work for Barbra or we take a walk. It's entirely up to you. Do whatever you like.' We had no real alternatives. We were most anxious to do the film with Barbra." But even if it means losing all artistic control, distributing the movie for First Artists? "I felt," says Calley, "that the worst thing that could happen was that if they took a shot at the screenplay and failed, we'd lose them anyway, but if they succeeded..." If they succeeded, Warners would get a Barbra Streisand musical for Christmas, following her projected triumph in Funny Lady, in a year when Warners isn't long on product.

"I told Jerry [Schatzberg] to stay loose and see what the two of them were able to do with the screenplay," Calley says. "He thought about it overnight and called me the next day and said, 'Listen, I don't want anyone else developing my screenplays.'" Jerry Schatzberg is walking off the movie. He is the fifth casualty.

Fall, 1974

Jonathan Axelrod is working on the fourth draft. He has turned in 55 pages of the new screenplay. He has not reversed the roles. But Barbra loves it. More: Jon loves it. Barbra has agreed to sign on the basis of the first third of the script. Peters starts interviewing new directors: Arthur Hiller, Hal Ashby. Warner Brothers has not completely turned the project over to First Artists although First Artists funds are paying Axelrod for writing the script that Barbra will agree to star in. To be very literal, Barbra has commissioned a screenplay for her company when the underlying rights to it are still owned by another company.

"The conflict came," Peters says, "when I decided I wanted to direct it. It's a story I felt only I could tell. I wanted to deal with it and not interpret it through another person. Barbra felt this was a wise choice, too." Did Warner Brothers agree? "I don't want to get into any negatives," Peters insists. "There were negotiations that went on for three months. It bounced back and forth because they wanted to control it, but then Barbra and First Artists had their way because Freddie Fields [president of CMA] wanted it at First Artists as well."

The bottom line, of course, is Barbra. Barbra wants the movie at First Artists with her boyfriend producing, directing and co-writing it - Barbra gets it. Freddie Fields and Sue Mengers are her agents and they are very powerful and persuasive but also, now that Jon is throwing his weight around, who knows? He is capable of getting angry with Barbra's agents and is apt to say to her, "Get rid of these dummies. You have me. What do you need anybody else for?" Already Joyce Haber has been running items in her column in the Los Angeles Times about Mengers' worries with this Jon Peters situation. Naturally, Sue Mengers puts pressure on John Calley; she wants to keep Barbra happy.

Calley makes the decision to turn it all over to Barbra.

Winter, 1974

Barbra finally finishes Funny Lady. She and Jon can now work full time on Rainbow Road. Their first move: firing Jonathan Axelrod. He has, apparently, failed. Peters feels he needs "meatier dialogue." He says, "Axelrod was the right person at the beginning because he was my interpreter. What you read in that script, I wrote. Now I need a real writer." Why don't he and Barbra take a crack at a re-write? "We're talkers," says Peters, "not writers."

Sue Mengers, therefore, is not concentrating on her bratwurst and beans as she lunches at the Polo Lounge. At the next banquette, Everett Ziegler, the literary agent, is having lunch with Bob Solo, the new Warner Brothers head of production. "Hey, Ziggy, you literary lion," Mengers yells over, "we need a writer for A Star is Born." "How about asking John Dunne to suggest one?" Ziggy replies. "Come on, I'm serious-there's money involved," Mengers insists. But Ziegler is not enthusiastic about finding a writer for that project. He seems to think the whole thing is a joke.

So Jon Peters starts interviewing screenwriters. He speaks with a soft-spoken television writer. But the writer cuts the meeting short, leaves the meeting mumbling that Peters is an idiot, that he won't be caught dead writing for him even if it means passing up a Barbra Streisand credit.

There is also a problem with the music. Richard Perry-the first choice of Rydell, Schatzberg and Barbra-has been meeting with each new director of Rainbow Road since winter, 1973. "In my last phone conversation with Jon Peters," Perry recalls, "he said, wouldn't it be great if the two of us could co-direct, be a real team, you know?" But Perry never hears from Jon Peters again.

Jack Nietsche, who scored Performance, is now called in. He had worked for a few days on the Butterfly album but freaked out; Peters thinks he'll do fine on Rainbow Road. He is, however, replaced a few weeks later by Rupert Holmes, an accomplished New York composer-arranger who once had a Number One hit with a song about cannibalism in mine shafts. Peters plunges into the work with him in December.

Now all Jon Peters needs is a director of photography and a good editor. And to lose the 15 pounds he's gained over the last six months. He sits in the Warner Brothers commissary, brooding about his movie. He does not order even half a grapefruit. "This is a young movie, young idea, young talents," he blurts out. "People in this town have it in for me because I'm young, you know what I mean? And I'm a bit uptight about directing this film, this is a big project, you know?" Yes, but with that good editor, good script and good cameraman, someone suggests, he'll be the equal of half the working directors in Hollywood. "Exactly, that's just what I think," Peters agrees. "That's why my editor is Dede Allen."

This creates a major silence at the table. Because Dede Allen, who edited Serpico and Bonnie and Clyde, is about as good as it gets. Maybe Peters knows what he is doing after all. But when Peters returns to his office and the phone rings - a call from Dede Allen - Jon Peters' press agent takes the visitors outside. "Jon wants to take the call in private," he explains. "He's never spoken with Dede Allen before."

Dede Allen turns Peters down. She suggests her young, former assistant. Jon Peters says, "Great! This is a young movie, we need young ideas, we need young talent."

Meanwhile, Kristofferson has yet to sign; his manager isn't even aware that Jon and Barbra have fired Axelrod. "Kris will not sign anything," his manager says, "until he sees the new script." By now, naturally, Peters is getting what he'd call "hassled." His sentences are delivered rapid-fire, with the grammar increasingly slurred. He no longer prefaces his sentences with "Barbra and I feel..." Now he begins, "I said" or "I told Barbra.. . ." He is pulling no-shows with writers, music people and his production crew.

In fact, Jon Peters is now yelling. "Directing is a thing I've done my whole life! It's getting people to do what I want them to do!" He kicks rocks as he strides around the 100-acre Malibu ranch. "If you had seen this place when I started, the fact that it was all dirt."

And in truth, the house is a cathedral-ceilinged, House Beautiful vision of ranch living: a powder room with marble counters, a fur lounging bed covered with antique pillows that doubles as the living room couch, and a bathtub built from natural stones cemented together. Barbra's things are everywhere. Boas. Hats. Pictures. Clothes. Health foods. Outside there are signs of expansion: land has been roped off for gardens and there is a hole where a natural rock swimming pool - a large outdoor version of the bathtub - waits to be finished. Through all this, the street-fighter who used to work out at the Main Avenue gym in downtown Los Angeles struts around like Nixon eyeing improvements at San Clemente. It does not matter to him that Joyce Haber snipes in his direction every time he says or does anything. He does not care that the men who lunch at La Scala and the Bistro, the men who run the studios, say things like, "Thank God those two aren't on our backs." He is not sensitive to the letters from angry First Artists stockholders who demand to know what is going on. He is not deterred by the news that his name brings snorts of laughter just about anywhere it's brought up in Bel-Air. The al bum he and Barbra have produced has just become a gold record. What Jon Peters appreciates very well is that he is living with a large entertainment corporation and that the merger looks permanent-particularly because his multinational corporation is thinking of marrying him.

That kind of power is rarely benign. It is not enough for Jon Peters to mastermind the career of his private conglomerate. He is not satisfied with a minor role as Barbra's shield, giving her the privacy she says she now wants. Yes, he sees himself as the take-charge guy in her business life-he says, "I have in my pluses (sic) a woman who, if she would get up on the screen and smile, the movie would do $20 million" -but even more, he sees himself as the lead in their larger-than-life movie, the one that so closely resembles A Star is Born.

Jon Peters, therefore, believes he is on the way up, all the way up. The only question now is the quality of the ascent. Which is why Rainbow Road must be made his way-because only he knows the special message he has for his best supporting actress. "What I'm really saying in this film is to Barbra," Peters explains. "Which is: you better check your act and see if it's the money or the success which is the most important thing. Are your goals the things that you really want to achieve? You gotta evaluate all the time. Because the danger in dreams is that you just might get them."

"What can I say? He makes Barbra happy. She's never looked better in her life," comments Barbra's agent, Sue Mengers. That few industry pros believe Barbra's company will survive another two years -Paul Newman has not renewed his commitment, the president of First Artists is out looking for a job -is of no particular concern. Barbra is a survivor, she couldn't care less that the SEC's comment on the First Artists setup was, "Giving performing artists creative control over their films represents a significant departure from traditional industry practice." After all, you don't get further away from "traditional industry practice" than Jon Peters.

But once you commit to someone like Peters, your most immediate problem is endlessly pleasing him. Because Jon Peters can be a very moody person. "Emotional," he'd say. Like at the Christmas party of Jon Peters, Inc., when he stands before a roomful of his employees and chokes up. "This is a very sad day for me," Peters says. "I won't be coming into the shop anymore to cut hair. I have to spend all my time for the next year with this film, you know?" It's very heavy for him. And, by extension, for her. Only Barbra isn't at the shop that day; she's not too interested in egg-nogging it up with Jon's stylists. And since Jon's lady didn't appear, well, the employees of Jon Peters, Inc., were told to come stag to watch their boss bid farewell.

But there is a bright side. New writers have been found -the Bob Dillons, who specialize in shoot-em-ups (French Connection II) -so Jon is sure that they will be able to pull off his home rock-umentary. "We had the most beautiful weekend with them," he gushes. "We're going up to Big Sur with them. We're going to throw away everything we've done up to now and start over again. We're going to make this a love story. They're the most beautiful people and the love they have for each other is the same feeling as Barbra and I have for each other. These last five months with Jonathan [Axelrod] have taught me what I don't want to do with this film. Now we're going to make it much closer to the 1936 version, the one with Janet Gaynor. That was magic. That's what we want to achieve."

And with that multinational corporation sharing his bed, Jon is just dying to show all of us fans waiting breathlessly that whatever a hairdresser believes, he can achieve. Right, Barbra?

END.

Page Credits: Magazine provided by Rafe Chase, from his collection.

Related Pages: