High Fidelity

May 1976

Streisand as Schwarzkopf

The voice that is "one of the natural wonders of the age" confronts The Masters

by Glenn Gould

[Barbra-Archives Note: Gould was a Canadian pianist who became one of the best-known and most celebrated classical pianists of the twentieth century. He was particularly renowned as an interpreter of the keyboard music of Bach.]

I'M A STREISAND freak and make no bones about it. With the possible exception of Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, no vocalist has brought me greater pleasure or more insight into the interpreter's art.

Fourteen years ago, an acetate of her first disc, "The Barbra Streisand Album," was being smuggled from cubicle to cubicle at CBS: I caught a preview, and laughed. Not at it, certainly—her eager mentor, Martin Erlichman, was simultaneously doing his own number in an adjacent office and it wouldn't have been good corporate policy in any case. And not always with it, either—though it was obvious even then that parody would play a vital role in Streisand's work. What happened, rather, was that I broke into a sort of Cheshire-cat grin that seems to strike its own bargain with my facial muscles, deigning to exercise them only when confronted with unique examples of the rite of re-creation.

Sometimes, this curious tic is caught off guard by novelty (Walter Cartos' Moog meditations on the third and fourth Brandenburgs, for example, or the Swingle Singers' scat-scanning of the ninth fugue from the Art of). Sometimes, it cracks up over repertoire for which I have no real affection. (I always felt that I could live without the Chopin concertos and managed to until Alexis Weissenberg dusted the cobwebs from Mme. Sand's salon and made those works a contemporary experience.) Sometimes, inappropriately perhaps, it surfaces in the presence of a work for which poker-faced solemnity is considered de rigueur. (Hermann Scherchen's boogie-beat Messiah was, for me, one of the great revelations of the early LP era.) Sometimes it conveys my relief upon discovering that a puzzle I had thought insoluble has fallen into place. (Strauss's Metamorphosen, for example, is a work I have loved, on paper, as a concept, for nearly thirty years but which I had long since written off as a vehicle for twenty-three wayward strings in search of a six-four chord. All that changed a couple of years ago when I first heard Karajan's magisterial recording. For weeks, night after night, on occasion two or three times per—I'm not exaggerating—I played that disc, passed through the eyes-uplifted-in-wonder stage, went well beyond the catch-in-throat-and-tingle-on-the-spinal-cord phase and, at last, stood on the threshold of ... laughter.) I have the same reaction to practically everything conducted by Willem Mengelberg or Leopold Stokowski and always—well, almost always—to Barbra Streisand.

For me, the Streisand voice is one of the natural wonders of the age, an instrument of infinite diversity and timbral resource. It is not, to be sure, devoid of problem areas—which is an observation at least as perspicacious as the comment that a harpsichord is not a piano or, if you insist, vice versa. Streisand always has had problems with the upper third of the stave-breaking the C-sharp barrier in low gear is chief among them—but space does not permit us to count the ways in which, with ever-increasing ingenuity, she has turned this impediment to advantage. I cannot, however, let the occasion pass without mention of a moment of special glory—the "Nothing, nothing, nothing" motif, securely focused on D flat and C natural, from the final seconds of that Puccini-like blockbuster, “He Touched Me."

In truth, though, one does not look to Streisand, as one does to Ella Fitzgerald or, as some will have it – I’m not sure that I will but that's another story – Cleo Laine, for vocal pyrotechnics. The lady can sing up a storm upon demand, but she is not a ballad-belter in the straightforward "this is a performance" manner of the admirable Shirley Bassey. With Streisand, who relates to Bassey as Daniel Barenboim to Lorin Maazel, one becomes engaged by process, by a seemingly limitless array of available options. Hers is, indeed, a manner of much greater intimacy, but an intimacy that (astonishingly, for this repertoire) is never overtly in search of sexual contact. Streisand is consumed by nostalgia; she can make of the torchiest lyric an intimate memoir, and it would never occur to her to employ the "I'll meet you precisely 51 percent of the way" piquancy of, say, Helen Reddy, much less the "I won't bother to speak up 'cause you're already spellbound, aren't you?" routine of Peggy Lee.

My private fantasy about Streisand (about Schwarzkopf, too, for that matter) is that all her greatest cuts result from dressing-room run-throughs in which (presumably to the accompaniment of a prerecorded orchestral mix) Streisand puts on one persona after another, tries out probable throwaway lines, mugs accompanying gestures to her own reflection, samples registrational couplings (super the street-urchin 4-foot pipe on the sophisticated-lady 16-foot) and, in general, performs for her own amusement in a world of Borgean mirrors (Jorge-Luis, not Victor) and word-invention.

Like Schwarzkopf, Streisand is one of the great italicizers; no phrase is left solely to its own devices, and the range and diversity of her expressive gift is such that one is simply unable to chart an a priori stylistic course on her behalf. Much of the Affekt of intimacy — indeed, the sensation of eavesdropping on a private moment not yet wholly committed to its eventual public profile-is a direct result of our inability to anticipate her intentions. As but one example, Streisand can take a lightweight Satie-satire like Dave Grusin's “A Child Is Born,” find in it two descending scales (Hypodorian and Lydian, respectively), and wring from that routine cross-relation a moment of heartbreakingly beautiful intensity. Improbable as the comparison may seem, it is, I think, close kin to Schwarzkopf's unforgettable musings upon the closing soliloquy from Strauss's Capriccio and, in my opinion, the bulk of Streisand's output richly deserves the compliment implied.

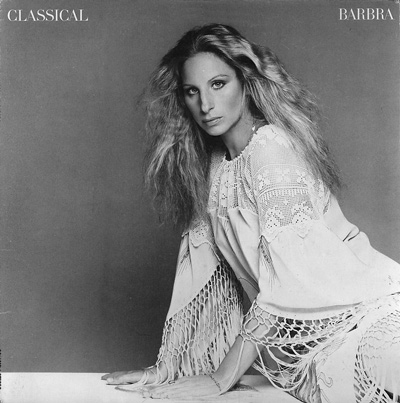

Unfortunately, the present disc is one of those "almost-always" exceptions. Another that comes to mind is the irritating sing-in for the Now-or, rather, Then-generation, "What About Today?," produced in 1969. Unlike that latter package, however, "Classical Barbra" is obviously not intended to placate the Zeitgeist. Other than as a curio, it can hardly be expected to attract musicology majors, its tight, pop-style pickup (personally, I adore it!) will almost certainly alienate the art-song set, and its contents over-all will quite probably turn off the casual M.O.R. shopper to boot.

So, a measure of courage is involved here; Streisand has obviously risked a good deal in order to cater to the boundless curiosity of her hard-core fans and, if only out of gratitude, we should make clear that, if this is not really a good album, it is certainly not a bad one either. It is considerate to a fault of the presumed prerequisites of the repertoire it surveys and, as such, to take the most obvious comparative route, puts to shame the ill-considered renditions of Broadway show-stoppers offered by such talk-show groupies from the classical field as Beverly Sills, Roberta Peters, or, occasionally, Maureen Forrester. (One should probably exempt Eileen Farrell, who really did "have a right to sing the blues.")

But it's the presumption of those prerequisites that causes problems. Nothing in this album is insensitive or unmusical-unless it's the gratuitous reverb slopped into the Handel orchestral tracks, which reaches a peak of stylistic defiance at the end of both excerpts where an engineer's quick pull on the pot only makes us more aware of its excremental presence. Throughout, though, Streisand appears awed by the realization that she is now face to face with The Masters. The entire album is served up at a reverential range of mezzo-piazo to mezzo-forte, and none of the cuts could be described as "up-tempo." Notwithstanding the fact that the lady is the most adroit patter-song purveyor of our time ("Piano Practice," "Minute Waltz"), this predilection for an unvaried sequence of andante grazioso intermezzi is not unique to this disc. It turned up as early in her career as "The Third Barbra Streisand Album," but was not then allied, as in the present instance, to an austere dynamic compression.

It is also virtually a one-sided performance; Streisand pulls out her choir-boy-innocent 8-foot and settles in for the duration. This is, to be sure, one of her most effective registrations and, when mated with appropriate repertoire, produces spellbinding results. For Orff's "In Trutina," Streisand, using the fastest vibrato in the west and the most impeccable intonation this side of Maria Stader's prime, provides a reading second to none in terms of vocal security while stripping this rather vapid air of its customary theatrical accouterments. More to the point, perhaps, she turns in the only current version possessed of exactly the right Book of Hours-like accommodation to the text.

In the "Berceuse" (from Canteloube's Songs of the Auvergne), Streisand cannot match the suave production of De los Angeles but, on its own folklike terms, her performance is quite extraordinarily touching. She does well with Debussy, too, and if Eileen Farrell, who also opened a Columbia collection with "Beau soir," stakes out her territory as a sophisticated Parisienne, Streisand replies, not ineffectively, as a Marseillian gamine.

It's in the German repertoire that Streisand runs aground. In Schumann's “Mondnacht" she keeps a maddening cool during the final stanza, plodding relentlessly through "Und meine Seele spannte, weit ihre Flügel aus." In Wolf's "Verschwiegene Liebe,” she simply sets aside her unique powers of characterization, keeping no secrets and wearing no veils.

About the most that can be said of her "Lascia ch'io pianga" from Rinaldo is that it is a model of analytic clarity when set beside the glissando-ridden 1906 production of Mme. Ernestine Schumann-Heink. Streisand delivers it according to the approved Royal Academy (1939) method – glissandos were out by then but ornaments had not yet been invented. (Ironically, it is left to Alfred Deller's superb collaborator, Eileen Poulter, to turn in the definitively Streisandesque version of this air.)

I do not, however, want to leave the impression that Streisand should give up on “the classics." Indeed, I'm convinced that she has a great "classical” album in her. She simply needs to rethink the question of repertoire and to dispense with the yoke of respectability which burdens the present production.

My own prescription for a Streisand dream album would include Tudor lute songs (she'd be sensational in Dowland), Mussorgsky's Sunless cycle and, as pièce de resistance — providing she'll pick up a handbook or two on baroque ornamentation – Bach’s Cantata No. 54. To date, in my experience, the most committed performance of this glorious piece was on a CBC television show in 1962. It featured the remarkable countertenor Russell Oberlin and a squad of strings from the Toronto Symphony. It also involved a harpsichordist/conductor of surpassing modesty who has requested anonymity; I am, however, assured by his agent that if Ms. Streisand would like to take a crack at Widerstehe doch der Sünde, and if Columbia would like to take a hint, he's available.

BARBRA STREISAND: Classical Barbra. Barbra Streisand, vocalist; Columbia Symphony Orchestra, Claus Ogerman, piano, arr., and cond. [Claus Ogerman, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33452, $6.98. Tape: MT 33452, $7.98; MA 33452, $7.98.

End.

[ top of page ]