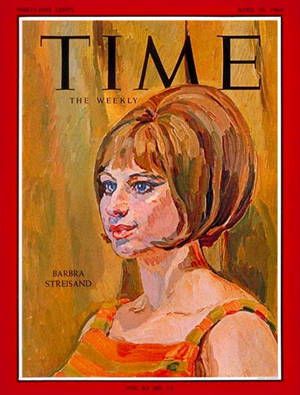

Time Magazine

April 10, 1964

S H O W B U S I N E S S —BROADWAY

The Girl

Barbra Streisand crosses the stage, stopping in the center to gaze out over the audience, her look preoccupied. She gives a shrug and goes off.

This wordless vignette is her first entrance and exit in Broadway's new musical, Funny Girl. In the moment's pause before she disappears as quickly as she came, she leaves an image in the eye—of a carelessly stacked girl with a long nose and bones awry, wearing a lumpy brown leopard-trimmed coat and looking like the star of nothing. But there is something in her clear, elliptical gaze that is beyond resistance. It invites too much sympathy to be as aggressive as it seems. People watching it can almost hear the last few ticks before Barbra Streisand explodes.

For the 24 hours that follow, she is all but the whole show. Funny Girl is a biographical evening about the late Fanny Brice, and ostensibly Barbra Streisand is recreating her rise to fame and her ill-starred marriage to Nicky Arnstein, the gambler-sport. But Streisand establishes more than a well-recollected Fanny Brice. She establishes Barbra Streisand. When she is onstage, singing, mugging, dancing, loving, shouting, wiggling, grinding, wheedling, she turns the air around her into a cloud of tired ions. Her voice has all the colors, bright and subtle, that a musical play could ask for, and gradations of power too. It pushes the walls out, and it pulls them in. She is onstage for 111 of Funny Girl's 132 minutes.

The Greatest.

Her impact was instant and stunning. Barbra's only previous acting experience on Broadway was a 20-minute role as a marriage-proof secretary in I Can Get It for You Wholesale, though her plaintive song called Miss Marmelstein was the only bargain in an evening that was otherwise strictly retail. Many people still say Who when they hear her name, but she is not from nowhere. She is only 21, but she has made an occasional $7,000 a week singing at places like Las Vegas' Riviera and $3,000 at Manhattan's Basin Street East. Her three albums have made her at present the world's best-selling female recording star on LP. But it is one thing to rival all the Patti Pages in pressed plastic and quite another to take over Broadway.

There is a convention in musical theater called The Girl's First Song—that first number in which the heroine states who she is, what she wants, and hints at the perils that might befall her, such as A Cockeyed Optimist from South Pacific and Wouldn't It Be Loverly from My Fair Lady. In Funny Girl, Barbra Streisand is to some degree playing herself as well as Fanny Brice, and it is something more than a statement in a show when she stands under the marquee of a theater and declares in her first song:

I'm the greatest star,

I am by far,

But no one knows it.

From that moment, no one has a chance not to know it. "I'm a great big clump of talent," she sings with conviction. "I've got 36 expressions— sweet as pie to tough as leather—and that's six expressions more than all the Barrymores put together. I'm the greatest star—an American Beauty rose, with an American beauty nose."

This nose is a shrine. It starts at the summit of her hive-piled hair and ends where a trombone hits the D below middle C. The face it divides is long and sad, and the look in repose is the essence of hound. She is about as pretty, in short, as Fanny Brice; but as she sings number after number and grows in the mind, she touches the heart with her awkwardness, her lunging humor, and a bravery that is all the more winning because she seems so vulnerable. People start to nudge one another and say, "This girl is beautiful."

Barking Bagel.

The show she dominates has a big New York sound, full of brass and sentiment, something that could have been written by Horatio Algerstein for the Ladies Home Journal. A poor Jewish girl with limitless fight and no visible assets claws, clowns and sings her way to the top of show biz. She marries a beautiful cardboard man and realizes her most soaring dreams of love, only to lose him because she is more successful than he.

As with Bobby Morse in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, the best part of Funny Girl is watching Barbra Streisand negotiate the climb. In blue bloomers and a red sailor blouse, she is dancing her feet off on Keeney's vaudeville stage when Keeney notices her and fires her. "You think beautiful girls are going to stay in style forever?" she barks plaintively. Has he ever considered what it would be like if all he had ever seen were onion rolls and in walked a bagel? "That's my trouble," she says. "I'm a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls."

Height of Nonchalance.

The bagel makes it at Keeney's and goes on to do everything But split and butter herself. Through the show, she has 18 costume changes and four hair Styles. One moment she is hurtling through the air in a celebrational block party, and the next she is singing a deepsong called People ("People who need people are the luckiest people in the world"). One moment she is staggering offstage under a 3-ft. floral headdress that might have been fashioned by a faggot Cherokee, and the next she is an eight-months-Pregnant bride in a mock-up Ziegfeld Follies production number.

So goes Funny Girl, a spun caduceus of Barbra Streisand the comic nut and Barbra Streisand the incomparable singer; Barbra Streisand in combat boots with red, white and blue bagels at her hips ("I'm Private Schvartz from Rockavay"); Barbra Streisand throwing her head back and really bringing a downpour with Don't Rain on My Parade. Her best comic scene is one in which Sydney Chaplin (as Nicky) comes to life long enough to seduce her. She joins him in a private dining room in a restaurant. "That color is wonderful with your eyes," he tells her. "Just my right eye," she says. "I hate what it does to the left." She gulps his sherry, hides her pâté under a chaise lounge, and sings:

Isn't this the height of nonchalance?

Furnishing a bed in restaurants.She gulps more sherry, pauses to wonder “would a convent take a Jewish girl,” circles the room on the run, and dives palms together onto the chaise to be had.

When the lights go up for intermission at Funny Girl nearly everyone dives into the Playbill to find out all about Barbra Streisand. They don't learn much. Barbra is still onstage even in the biographical notes. She writes them herself. Her lifework has been to elevate and sculpt her own archetypic personality, and no string of drab printed facts is going to get m her way.

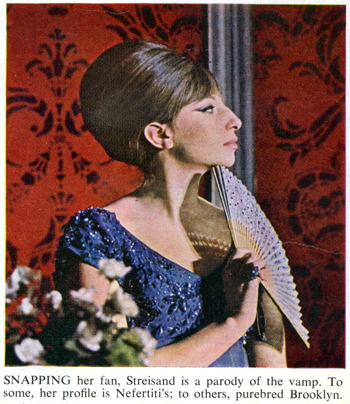

In Playbill, she says that she strings beads and likes old shoes, but does not mention where she was born. In the Playbill for Wholesale, she said that she was born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon. It was easy enough to believe. After two martinis and an expense-account steak, Barbra's Pharaonic profile and scarab eyes suggest the Aswan High Dam. Netertiti, and the whole Afro-Asian bit. Some minor poets have even brooded over her fathomless Mesopotamian stare, as if her unique countenance could only have developed somewhere between the Tigris and the Euphrates. In truth, however, she was born and raised between Newtown Creek and the Gowanus Canal.

No Hands.

Her recollections of a Brooklyn girlhood are somber. "It was pretty depressing, and I've blocked most of it out of my mind," she says. She never knew her father. He was a school teacher who died of a cerebral hemorrhage when his daughter Barbara Joan was a year old (1943). Her mother spent the next three years lying in bed, crying, and living on her brother's Army allotment checks until the checks stopped and she took an office job. Barbara spent her days in the hallways of the six-story brick apartment building they lived in, accepting handout snacks from neighbors.

As a slightly older kid, she used to go up on the rooftop, smoke, and think about being the greatest star. Down in the apartment, her mother warned her never to hold hands with a boy. "I never took part in any school activities or anything," Barbra remembers. "I was never asked out to any of the proms, and I never had a date for New Year's Eve. I was pretty much of a loner. I was very independent. I never needed anybody, really."

Her average at Erasmus Hall High School was in the 90s all the way. She worked in the evenings at Choy's Orient, the local wontonnery. "I loved the idea of belonging to a small minority, she says. I was them against us in the Chinese restaurant."

And she worked on the personality that was to be Barbra. "I used to spend a lot of time and money in the penny arcades taking pictures of myself in those little booths. I'd experiment with different colored mascara on my eyes, try out all kinds of different hair styles and sexy poses."

Last Cough.

When she was 14, she made her first trip out of Brooklyn—a subway ride to Manhattan to see The Diary of Anne Frank. "I remember thinking that I could go up on the stage and play any role without any trouble at all," she says. After school at home, she used to smoke in the bathroom and do cigarette commercials into the mirror, but she never bothered to go out for school plays. "Why go out for an amateurish high school production when you can do the real thing?"

Up she went to the Malden Bridge Playhouse near Albany for a summer of the real thing—washing out toilets, changing scenery, riding a goat manqué across the stage in Teahouse of the August Moon. Back home, she ushered in Broadway theaters during Saturday matinee and evening performances. About then, she decided that she only had six months to live. "You realty appreciate life when you know you're going to die," she discloses. But before the last cough, she began making the rounds of actors' workshops, consulting the New York City telephone directories for a suitable pseudonym, and unquestionably finding a name in 8,000,- 000—Angelina Scarangella, name Barbara Streisand from getting bruised by uncouth hands. She had no desire to drop her own name—"because I wanted all the people I knew when I was younger to know it was me when I became a star." She hated her first name, though, and took an a out of it to shape it up. Today she likes to tell interviewers: "I don't care what you say about me. Just be sure you spell my name wrong."

Moving to Manhattan, she shared an apartment for a while, but then began lugging a portable cot around with her and mooching space where she could—in friends' apartments, public relations offices, studio lofts. She swept the floor at the Cherry Lane Theater and took acting lessons from Drama Coach Allan Miller and Eli Rill. She dyed her hair red, wore white makeup, and dressed in black tights, feathered boas and 1925 hats. Barbra has never striven to be inconspicuous.

Singing Actress.

At this point, she had no interest in her innate comic abilities. "She was curious when the other students laughed," remembers Rill. "I kept telling her she had to develop what she had and not try to be somebody else. She would make it clear that my role was to make her into a tragic muse." She had no intention of becoming a singer either, but one day she heard about a remunerative amateur contest at a little Village binlet called The Lion. Learning A Sleepin' Bee, she sang it and resoundingly defeated a light-opera singer, another pop singer and a comedian. Almost at once she had a booking at the Bon Soir, the Copacabana of West Eighth Street. Barbra by then had developed an enduring fondness for other people's castaway clothes, particularly if the other people had cast them away at least 30 years before. These come cheap in Manhattan's thrift shops. When she first walked into the Bon Soir, she was wearing a $4 black dress, a $2 Persian vest, and old white satin 50¢ shoes with large silver buckles.She introduced “Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf” there. It was the same song that children sing. But in her version, it seemed new, tripping perilously along the edge of probability, its innocence in doubt between the ceiling and the floor, which had suddenly become the dripping jaws of some unruly canine. And she is still experimenting in search of style. In one number there are conscious echoes of Jolson, in some others perhaps unconscious ones of Lena Home. She has a bit of Judy Garland, a hunk of Merman, and a whisper that brings Julie London to mind. But whatever echoes or familiar inflections may be circling the periphery, there is always something strong and Streisand coming through. She takes a role in every song. As she puts it, "I work as an actress when I'm singing."

She sings often too close to the top of her emotional range. Nearly every song has a gasp, a weep, a shout. As one bass player once said: "She loses her cool."

Her essential gift is interpretation. She forms an idea of a song that is hers alone, and she makes it work. The master sample of this talent is her recording of Happy Days Are Here Again, sung so slowly that suddenly all the hidden irony and banality of it come shaking out like loose nails. The song had been around for more than a generation, but not until Streisand sang it was it ever more than a jingle.With success at the Bon Soir, she needed plenty of new songs but had none. She called music publishers, said she was Vaughn Monroe's secretary; would they please send over some complimentary sheet music? It worked. Her brother Sheldon, an art director in the advertising business, used to take her to lunch in those days and make her walk three feet behind him because of her clothes. People stared at her. "She had these horrible rips in the back of her stockings," Sheldon remembers vividly. ''I offered to buy her a new pair. She said, 'They're not ripped in front and I don't see them in back, so they don't bother me,' and refused to change them." She did give up her nomadic nights, however, snd took an apartment over a Third Avenue seafood restaurant. Essence of decaying halibut came up through the floor boards, and in the summer the place smelled like the stomach lining of an alley cat.

Realistic Fear.

Her public character was beginning to get across. Televisions Mike Wallace made her the semi-resident nut on his PM East show. She made about a dozen appearances and in each one seemed to be straining a little harder to live up to her own axiom of eccentricity. "I scare you, don't I?" she said to Wallace's guest David Susskind one night. "I'm so far out I'm in." She was only trying desperately to be different, with an old realistic fear that with her unprepossessing looks her only alternative was stenography. Yet all through that era, people were telling her that she must have a carpenter surgeon plane down her nose. "That would be cheating," was Barbra's reaction. "It wouldn't be natural, know what I mean?" She has also been warned that such an operation might well change the quality of her voice.

Burnt Fingers.

The span from Bon Soir to Funny Girl took only 3 ½ years. But she became well enough known through Wholesale, TV shows and nightclub dates to be asked to Washington to sing for President Kennedy. Her opening line to the President was: "You're a doll." When he inquired politely how long she had been singing, she said: "As long as you've been President."

But she was virtually inexperienced as an actress when she began rehearsals for Funny Girl, and the show turned out to be one of the most fussed-over, reworked, overmanaged, multidirected Broadway productions ever—imposing expectations on its star that would have broken someone who lacked her will.

Producer Ray Stark was feeling his way and burning his fingers on almost everything he touched. A fabulously successful film producer (Seven Arts Productions), he had never before done a Broadway show. Furthermore his wife Frances is the daughter of Fanny Brice and Nicky Arnstein. So there were book problems right away. The actual Nicky was considered unacceptable as a leading man. He was a shiftless con man with a column of mercury for a spine, a criminal record, and a cavalier attitude toward Fanny's devotion and fidelity.

But there was more to the old Nick than a Ph.D. from Sing Sing. He was a man of resplendent metaphor. His shoe trees were casts that had been made from his feet, and he described himself as distingué. W. C. Fields modeled his style, his speech and his manner after Nicky Arnstein. Something quite approximate to the real Nicky might have cured the flaws in Funny Girl. Instead, Stark settled for a paraffin prince out of Franz Lehár, who only turns to fraud out of temporary insanity arising from his embarrassment over accepting hand-outs from Fanny. Hence Barbra Streisand has no competition on the stage. A fight to the death with a more vigorous Nicky, given plenty of songs of his own, might have balanced the night.*

Odd Sounds.

While Ray Stark was worrying about these things, Funny Girl opened in Boston and bombed. Writer Isobel Lennart began rewriting. Composer Jule Styne wrote twice as many songs as were finally used, and on the road $30,000 worth of sets were thrown away. Isobel Lennart wrote 42 versions of the last scene alone. The cost of the show eventually climbed beyond $600,000. The date of its New York opening was changed four times. Five weeks before the New York opening, Garson Kanin was no longer directing, and Jerome Robbins was.

The trouble was not all in the second act, although that is what the giant brains were concentrating on. Some of the difficulty was with Barbra Streisand. In Boston she showed no flair for stage comedy, and merely sang the songs as they came along. In the 15 weeks that Funny Girl drifted toward Broadway, she picked up ten years' worth of stage presence and comic sense.

At first, in Boston, the wonderfully funny seduction scene was played straight. Barbra, something of a director herself, inspired the change to farce. She also proved to be an unbelievably quick study. One day during the New York previews, she was handed three new scenes and half a song, and she delivered them all flawlessly that evening. She even overcame electronic hazards. Although she has a big voice, she wears a microphone in her cleavage to help get the low, soft songs up to the balcony. The batteries are taped to her bottom. On opening night in Boston, this apparatus began receiving police calls that were audible beyond the footlights.

Sense of Courage.

When Funny Girl finally opened, the novice star had added to her performance a dazzling spray of gestures, inflections and a hundred small takes. She was ready to carry the show on her own.

Her intensive education in the tryouts did more than produce a star for a single show, a female Ernest Borgnine doomed to television remembrances of Marty. She is the sort that comes along once in a generation. She has more than mere technical versatility. The real force of her talent comes from an individual spirit that is unique, a kind of life force that makes her even more of a personality than a performer. "She carries her own spotlight," says Jule Styne as a simple statement of observable fact.

People who knew and loved Fanny Brice say that Barbra's approximation of her is warmly moving and sometimes almost incredibly exact, but Barbra has never heard a Fanny Brice record or seen a Fanny Brice movie. Similarity draws from the shared Eastern-asphalt accents of the two women, from close resemblances in their wide mouths and angular gestures, and even more from the sense of courage that both put across in the act of provoking laughter.

Smoke Together.

For all her brilliance, Barbra Streisand's confidence could still use a few years on the road. Broadway's critics gave her everything but frankincense and myrrh; yet she wondered why their reviews were not more enthusiastic and decided that they were ganging up upon her in an inexplicable personal attack. "All right, what is it? Am I great or am I lousy, huh? I need to know," she kept saying to anyone in sight last week.

Anyone generally included Elliott Gould, 25, her tall and attractive husband, who was the leading man in I Can Get It for You Wholesale. He, too, comes from Brooklyn. They have been married for a year. He seems to understand her better than anyone ever has, and he speaks of her quite humorously, freely and often movingly.

He saw her first at an audition for Wholesale and thought she was "the weirdo of all times." But "when I saw her next, I offered her a cigar and we had a smoke together. She was always kind of a loner. And the more I got to know her, the more I was fascinated with her. She needs to be protected. She's a very fragile little girl. She doesn't commit easily. I found her absolutely exquisite. As conventional beatniks go, she's different-looking. I had this desire to make her feel secure.

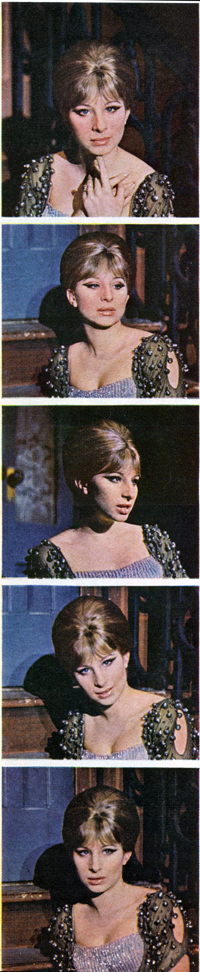

Photo below: Ormond Gigli

"A couple of weeks later, we were having a snowball fight at 2 o'clock in the morning at the Rockefeller Center skating rink. She threw pretty well, but I'm competitive and I have this hex on her. Anyway, I very delicately washed her face with snow and then kind of touched her lips. It wasn't very demonstrative. She's desperately insecure. She always thought of herself as an ugly duckling, and she made herself up to be weird as a defense. She liked me. I was the first person who liked her back."

Free Fragrance.

With the fine flush of success, Barbra has hastily assembled some of the accouterments of the gracious life, but is plainly still out of phase with it. She has rented a penthouse duplex on Central Park West that was once the home of Lorenz Hart during the great lyricist's last years. They have had the place about seven months, and it is still substantially empty, but Barbra is filling it with her own brand of antiques, the pursuit of which is her only hobby. She has an old dentist's cabinet for her ribbons and lace, an apothecary jar filled with beauty marks, a Wedgwood slop bucket, slabs of stained glass ready for installation, an old captain's desk, Portuguese chairs, 50 used hats, and 80 ancient shoe buckles on as many ancient shoes, which she wears.

Every day begins with Elliott shouting over the intercom from the floor below: "Barbra, come and get your chicken soup." In Hart's day, the apartment's focus was the bar. Now it is the kitchen, whose walls Barbra has covered with red patent leather. She neither drinks nor smokes, but she eats like a woman thrice her weight, which is 125 lbs. The kitchen is a self-service delicatessen heavily stocked with matzo brie, gefilte fish, grapefruit wedges, kosher salami, pickled beets, tzimmes, caviar, corn fritters, brownies, ice-cream rolls, cottage cheese, sweet potatoes, and enough frozen chicken TV dinners to pave the Piazza San Marco.

She is also a connoisseur of baked potatoes; she particularly "likes them baked one day and reheated two days later when they get "hard on the outside and mooshy on the inside." But her consuming passion is coffee ice cream, specifically in Breyers bricks. Elliott brought cartons of it to her while she was out of town with Funny Girl. She is installing a small refrigerator beside the bed upstairs so she can eat virtually unlimited amounts of it while lying under the covers and watching horror movies on TV.

The place is full of jaunty poltergeists. Whenever the phone rings, the TV set changes channels. There are only two books in sight: Franny and Zooey and How to Achieve and Maintain Complete Sexual Happiness in Marriage. Two dozen gardenias are delivered to the apartment each week. They float in an urn in the kitchen, a salad bowl in the dining room, a champagne glass in the bathroom, and a wooden bucket beside her bed. "A gardenia is like a free spirit," she says. "Its fragrance cannot be captured. It's like it doesn't want to be tied down and destroyed by all the sterility of the modern times.”

Barbra, suffering from a few personal poltergeists herself, slips easily into the psychoanalytic ambiance of modern times. "I think sensory," she says. "I don't have any trouble turning myself on or off. I just hate to become too intellectual. I always tell Elliott, talk to me sensory." Ray Stark, with an exhausted expression, says that "she'll drive you bats with too much analysis. It's not arrogance, but doubt. She is like a barracuda. She devours every piece of intelligence to the bone." One of her actor friends says that "she is like a filter that filters out everything except what relates to herself. If I said, 'There's been an earthquake in Brazil,' she would answer, 'Well, there aren't any Brazilians in the audience tonight, so it doesn't matter.'"

She still has the haggling instinct of her Brooklyn childhood and sometimes puts the weight of her new fame behind it, often insisting on discounts at local stores ("Listen, don't I deserve a discount or something? I mean, after all"), or ordering a secretary to "tell them that if they want my business, they'd better knock $2 off that bill."

Photo: Ormond Gigli

Whatever I Am.

Sure that she wanted to become a star, Barbra Streisand is now not sure that she wants to be one. "I had to go right to the top or nowhere at all," she says. “I could never be in the chorus, know what I mean? I had to be a star because my mouth is too big. I'm too whatever-I-am to end up in the middle. The exciting part has been trying to get to wherever it is I'm going. It was exciting to get kicked out of all those casting offices."

More than willing to forsake her anonymity, she has nonetheless felt the pain of its loss. People who recognize her in the street and ask for her autograph have always made her uncomfortable. Some of these people wear their hair like Barbra Streisand and display a glassy, communicant look when they see her, for she is a godhead in their most privately inarticulate reveries. Others who stop her are just impious strangers. They see her tasseled yellow blouse showing through under a South American skunk coat, her white wool slacks and dirty sneakers, her induplicable face, and they say, "Hey, you look like Barbra Streisand."

“Yeah," says Barbra, "someone else told me that."

* Now 83, Nicky lives in a seedy downtown Los Angeles hotel, where he declined to talk about Funny Girl because he had a heart attack last month and '"the doctor says I'm not to get excited."

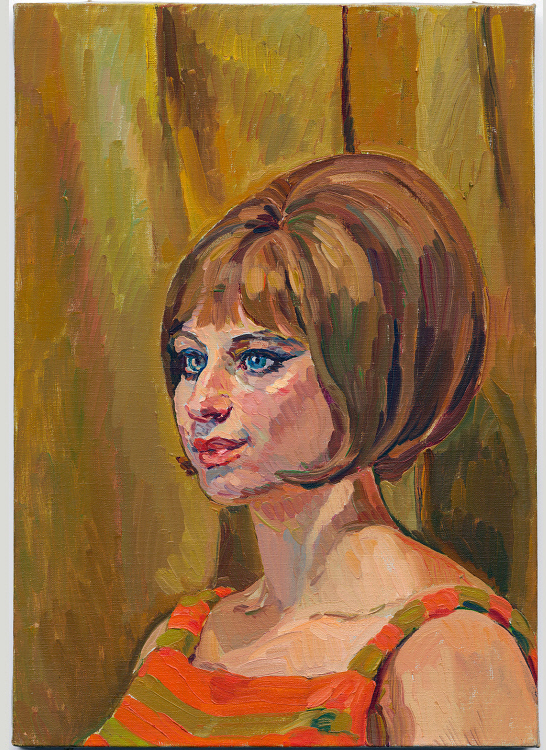

About the Cover

(Above: Model and artist Koerner)

A Letter from the PUBLISHER (Berhard M. Auer)

[Barbra Streisand's] opening in Funny Girl was witnessed by a contingent of Time editors who, with rare unanimity, loved the show. “We went to the cast party afterwards, high atop the RCA building,” recalls one, “and in that heady atmosphere decided to do a cover instantly.”

In Barbra's half-furnished penthouse, artist Henry Koerner painted the cover portrait in three sittings, while “interior decorators were coming in by the droves.” More or less at the same time, she also managed to run through scenes from the show for photographer Ormond Gigli [...] and to rove the town with reporter Ray Kennedy, shopping for antiques, shoes or Fudgsicles. Says Kennedy: “I felt as if I were on a teen-age date.”

Barbra-Archives Note:

The original Henry Koerner painting of Streisand hangs in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

END.

Related: Funny Girl (Broadway)

[ top of page ]