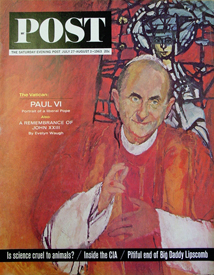

Saturday Evening Post

July 27—August 3, 1963

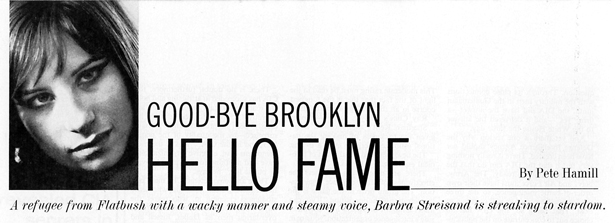

On a recent Sunday afternoon in New York an angular young girl with the nose of an eagle, slightly out-of-focus eyes, and a mouth engaged in battle with a wad of gum walked up to the stage entrance of the theater that houses The Ed Sullivan Show. A beefy young man in a guard's gray uniform stopped her.

"Whattaya want, girlie?" the guard said, looking for the inevitable autograph book.

"I want to go in," she said. "I'm in the show."

After a brief debate the girl proved that she was not there to acquire the signatures of Sullivan, the McGuire Sisters, or the 27 members of the visiting Mexican soccer team scheduled for the TV program. She was there to rehearse, and her name was indeed plastered across the theater's marquee.

"Barbra Streisand," the guard said admiringly at the close of the show. "To tell you the truth, I never heard of her. But she's really something, ain't she? Really something."

Such long, low expressions of approval are being echoed by an ever-widening circle of admirers whose members range from Truman Capote to a President named Kennedy. At 21, with only three and a half years of professional experience, Barbra Streisand is on her way to becoming one of the most glittering stars of the 1960's.

As a singer Barbra Streisand cut her first album for Columbia Records this year, and four weeks after its release she was the best-selling female vocalist in the country. As a nightclub performer she has graduated from the Greenwich Village coffee circuit to such opulent drinking emporiums as New York's Persian Room. Her fee has jumped in three years from $108 a week to $7,500, and is climbing. As a television performer she came across with such vigah on a Dinah Shore special that one viewer—President Kennedy—promptly had her invited to perform at a White House correspondents dinner. And although her Broadway credits consist only of a supporting role in the musical I Can Get It for You Wholesale, she will star next winter in a musical comedy based on the life of the late comedienne Fanny Brice. "She will knock everyone dead," predicts the musical's producer, David Merrick.

To many observers her overnight success is bewildering. Show business, after all, is largely a bazaar for that tinselly commodity, glamour. To achieve stardom, unendowed young girls customarily acquire bobbed noses, capped teeth and cantilevered underwear. Not Barbra Streisand. "I'm me," she says with a disarming shrug. "And that's all there is."

What there is would hardly launch a thousand ships. Her blowzy, reddish-brown hair slops over a pair of blue eyes that appear crossed, and her nose would fit just as comfortably on Basil Rathbone. She is five feet five, but looks taller because of the boniness other 110-pound body.

But when she begins to sing, Barbra Streisand suddenly is transformed. Her eyes fixed on some distant point in space, her voice moony, her head cocked to the side, she somehow manages to combine the most engaging qualities of an Egyptian wall painting and a seductive spook. Her approach to humor, which might best be described as cuckoo, complicates the picture. "The hills are alive," she may softly sing as she launches into the most sticky song from The Sound of Music, only to blurt, "... and it's pretty frightening." Or she may embark on a serpentine introduction to an Armenian folk song about an ill-starred butcher named Arnie, which she somehow never gets around to singing. She creates her big moments, however, with the staples of her repertoire, which range from a love-hurt version of Cry Me a River to a driving, rollicking interpretation of Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? She has a large voice, rich with nuance, and throbbing with so much feeling that some critics have accused her of laying it on too thick. But if the voice were all, it would not explain why watching her is such a moving experience.

"I think she's got what Chaplin had," says Marty Erlichman, her thick-set, young personal manager, who is one of her closest friends. "I've had to figure it out as a man, not a manager, and I think it's Chaplin. As the little fellow, people wanted to help him, and they were happiest when the worm turned. Barbra is the girl the guys never look at twice, and when she sings about that— about being like an invisible woman —people break their necks trying to protect her."

Accident of geography

"It's weird the way it happens sometimes," Barbra herself comments. "But I really can't verbalize about it. I'm afraid that if I did, I'd analyze it all out the window."

Most of her friends say that it would be almost impossible for Barbra to analyze out the window the quality of urban loneliness laced with the occasional small triumph that is her style. "She's telling you the story other life every time she gets up there," says one friend. "And the facts of that life have made her very sensitive."

One of the facts other life that she is strangely touchy about is the accident of geography that caused her to be born in Brooklyn on April 24, 1942. Barbra's father died when she was 18 months old, her mother remarried, and by the time she was in her teens, Barbra was laying plans to escape from that bosky dell known as Flatbush. “To Barbra,” one friend says, “Brooklyn meant baseball, boredom and bad breath.” [see note]

Her escape route lay through the golden world of show business. But before she received her passport there were a number of roadblocks. For one thing, she had the bad fortune to enroll at a Brooklyn high school where the atmosphere was gluey with fraternities, sororities and 14-year-old couples who exchanged sweatshirts. In addition to her modest looks, she was also an honor student, and the combination frightened off most of the young men. "I had these dreams of being a star," she says, "of being in the movies, but in Brooklyn, I always felt like a character out of Paddy Chayefsky."

While in high school Barbra enlisted as a part-time student in three different Manhattan acting schools. After graduation, she spent a few weeks in summer stock, moved into a Manhattan apartment and, to feed herself, took a job as switchboard operator in a printing plant. Her big break occurred almost by accident.

"It was weird," she said. "They fired me and I started taking money under false pretenses from the unemployment people. To get the money, you had to look for a job. I was looking for a job, but as an actress, not a switchboard operator. They checked up and cut off my checks.

"So there I was, out of money and out of work. And then I entered this talent contest in a bar in Greenwich Village. Not as an actress though. As a singer—even though I'd never had a lesson."

They laughed when she stood up at the microphone, but when she began to sing it was no contest. She won, and a few weeks later she was singing for $108 a week at the Bon Soir, a tiny Greenwich Village nightclub. In due course she was booked into that nursery of talent, New York's Blue Angel. One night, as in all show business sagas, the great producer strolled in to hear her. This one was named David Merrick.

"She was a skinny flibbertigibbet with no discipline and no technique," Merrick remembers. "All she had was this enormous talent."

Merrick decided she would be perfect as Miss Marmelstein, the under-loved secretary in the musical version of Jerome Weidman's garment- industry novel, I Can Get It for You Wholesale. He arranged for an audition, and Weidman, who adapted his novel for the stage, remembers the impression she made. "When we heard this kid, she just knocked us off our ears. (Composer) Harold Rome and I sat down and immediately expanded the role. You see, when you have a talent that large on the stage, you just can't let her wander around. You have to give her something to do or she'll kill you: she'll steal scenes, make up business, throw people off cues."

When the show opened in March, 1962, Barbra did kill everybody, including the critics. The show received lukewarm reviews, but on the strength of her performance the show ran nine months.

During the run of Wholesale two events of supreme importance took place. She met and fell in love with another Brooklyn exile—Elliott Gould, the handsome, 24-year-old star of the show. And she became established as a character. At New York's Basin Street East, Barbra wowed patrons with zany talk and zippy attacks on such tunes as "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?"

She became a character by playing the role of someone named Barbra Streisand. She started off by giving Playbill, the official program in all New York theaters, a biography which listed her as born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon ("those biographies are always so dull," Barbra explained later). In newspaper interviews and on the Johnny Carson and Mike Wallace TV shows she displayed a dazzling conversational style that seemed influenced by the later works of James Joyce, with subtitles by Casey Stengel.

"I like food, sleep and clothes," she said recently. "And I like to read. I once went through a Chekhov period when I let my nails grow. Food is a tangible thing, and so is sleep. When you're tired, it's so great. When I was a kid I studied Italian and even stole Italian books from the library. I used to steal candy too. Cinnamon hots, jujubes and even salt shakers. I love salt shakers, especially those fancy ones. Does that make me so special? People used to say to me, 'You're special.' But all songs are something special, aren't they? After all, I'm not singing about nuclear fission. I'm singing about people."

"Her gift of gab made her famous," says one friend, "but the marriage to Elliott was much more important. Here was a girl from Brooklyn who never had the guys chasing her, never went steady and who really felt ugly inside. And then the leading man, a big, handsome, virile guy, falls in love and marries her."

Today Barbra Streisand no longer feels ugly inside, and has left Brooklyn long behind. Since her marriage most of the insecurity has disappeared, and with it the lack of discipline that was her largest flaw. "I was late thirty-six times for Wholesale," she remembers, "but I had other things to think about."

She still frets about unflattering photographs, but she has firmly decided against doing anything to her prominent proboscis. With the promised security of the Fanny Brice role, she and her husband are planning to take a long-term lease on an apartment and attempt to make something of that most fragile of unions, the show-business marriage.

"It takes a fantastic amount of ego and immaturity to stand on a stage and do absolutely nothing and yet be powerful," she says. "Acting is really so ludicrous, so childish. But it's something you must do. And yet it's something you have to keep in perspective too.

"They tell me I'll eventually win everything. The Emmy for TV, the Grammy for records, the Tony on Broadway and the Oscar for movies. It would be beautiful to win all those awards, to be rich, to have my name on marquees all over the world. And I guess a lot of those things will happen to me. I kind of feel they will. It could be good or it could be bad, but I'm living my life one day at a time. And I don't see why it shouldn't always be fun. Do you?"

THE END.

[Note: In 2009, Streisand wrote the following Truth Alert on her website regarding the Brooklyn quote:

There are some quotes that are so erroneous and so offensive that they have to be stopped in their tracks.

A 1963 article by Pete Hamill in the Saturday Evening Post stated: "'To Barbra,' one friend says, 'Brooklyn meant baseball, boredom and bad breath.'" That conclusion couldn't have been further from the truth. But a book published subsequently actually attributes that offensive phrase to Barbra Streisand herself, either carelessly or intentionally twisting Hamill's report.

Setting the matter straight before it gains any traction: she never said anything like that, she never thought anything like that and she seriously doubts that any friend of hers could have so misjudged her.

Then, in Feb. 2010, Streisand addended her Truth Alert with more comments on the Brooklyn quote:

I wanted to write an addendum to the Truth Alert I posted below because I couldn’t stop thinking about which “friend” could possibly have so misjudged me. I decided to track down Pete Hamill, who wrote the 1963 article that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.

I found Pete down in Mexico and asked him if he remembered who this so-called “friend” was that falsely quoted me. He said it was either a Harvey something, possibly a partner at a public relations firm that represented me years ago, or Max Gordon, the owner of the nightclub, the Blue Angel, where I had performed. My interaction with both of these men was very limited. I said hello to Harvey Sabinson maybe twice in the 26 years his PR firm, Solters and Sabinson, represented me and I had never socialized with Max Gordon. I was happy to finally find out that the source who provided the erroneous quote was not a friend, but a business associate with whom I had virtually no relationship.

I have been in the process of writing my own book, My Passion for Design, and I know how important it is to make sure that the information I include is accurate. I always hope that the journalists who choose to write about me hold themselves to the same standard.

ps. I really dislike that all these years Brooklyn had to be demeaned. I’m very proud to have come from there.

Outtakes from Photo Session

I believe the uncredited photographer for this article was Burt Glinn. There is a whole series of photographs of Streisand backstage at Basin Street East, wearing the same black blouse.

End.

[ top of page ]