Redbook

January 1968

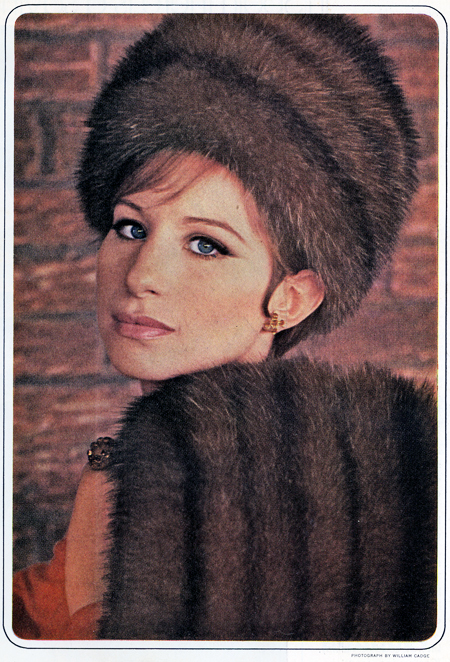

Her Name Is BARBRA

by Martha Weinman Lear

And she is warm, cool, honest, devious, elegant, vulgar, simple and enormously complex. But most of all Miss Streisand is, as she herself will gladly tell you, instinctively, intuitively— and maddeningly—almost always right.

"Barbra's voice has been a little off lately, and she knows it. She had the baby by cesarean and wasn't feeling too well and she didn't sing for about ten months. When she's 'off,' her singing is about twenty-five per cent better than anyone else's, but that's not good enough for her. She isn't satisfied unless she's operating at her own full capacity. Why? I suppose you could call it a searching for love, respect, affection — the usual reasons.

"You know, I think the baby has mellowed her somewhat. The baby has replaced other things she may have been driven by. She's always been a fantastic perfectionist, but now, you see, she's expected to be perfect. When you have to be a queen every time you perform and you're only twenty-five and you're a very thoughtful, vulnerable lady— well, it's hard."

And then actor Elliott Gould — 29 and a thoughtful, vulnerable gentleman — peered at me and asked gently, "Hey ... are you going to write nice things about my wife?"

If the people closest to Barbra Streisand seem exceedingly protective, as they are, and if she herself seems exceedingly defensive, as she is, it is understandable enough. In her short, brilliant thrust to the top she has been given a lot of irrelevant grief. She can give as good as she gets, and sometimes better (how many, after all, rise to the top through nonviolence?) but it is hard to defend oneself against the printed word, and much of her grief has come in print. Being interviewed is not her favorite pastime.

Perhaps the difficulty is that journalists— particularly gossip-column journalists, who have knocked her the hardest — need news. Good news in no news, so Miss Streisand must be bad. If she is not bad as a performer, perhaps she is bad as a person. Thus in Hollywood, where she is making the film version of her Broadway hit Funny Girl, she is said to be "difficult," "temperamental" and "unfriendly." Is she? Of course she is. She is also, if one views the matter differently, conscientious, a perfectionist and shy. But who wants to read about Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm?

Perhaps the difficulty is that journalists— particularly gossip-column journalists, who have knocked her the hardest — need news. Good news in no news, so Miss Streisand must be bad. If she is not bad as a performer, perhaps she is bad as a person. Thus in Hollywood, where she is making the film version of her Broadway hit Funny Girl, she is said to be "difficult," "temperamental" and "unfriendly." Is she? Of course she is. She is also, if one views the matter differently, conscientious, a perfectionist and shy. But who wants to read about Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm?

I have interviewed Miss Streisand twice—most recently for this article. Two years ago when I interviewed her for another national magazine I found her warm, cool, honest, devious, simple, complex, elegant, vulgar, enormously sophisticated and colossally ingenuous. This time I found she had married; she had become more of everything. In short, she has all the usual foibles—magnified by celebrity—of unusual people. She resists pigeonholing adamantly.

In the two years since I had seen her, she had enjoyed a fine triumph in London with Funny Girl; she had had a baby, Jason Emanuel, who is now almost a year old; she had pushed seven albums over the million-sales mark; and she had become a famous movie star before making a foot of film. (On the basis of no movie exposure whatever she had been signed to Funny Girl; Hello Dolly! and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.) And still the journalists question darkly whether she is "really nice," "really beautiful" or "really natural," and it is all monumentally unimportant. What is important is that she makes it work.

She makes it work. Ultimately her mentor is Barbra Streisand. Her manager is Barbra Streisand. Her image-maker is Barbra Streisand. Nobody has a stronger sense of what is right for Streisand than Streisand herself. Her intuitiveness struck me when we first met as her strongest quality. It has grown stronger with time.

One evening last summer in Central Park, I watched Miss Streisand and a 60-piece orchestra in full-dress rehearsal for an open-air concert to be held the following night. She was wearing a copy of one of her Funny Girl costumes which she adores. "You can pack it like this," she said, twirling an imaginary lasso in the air. It was pink and strange, very period, vaguely boudoir, with an interminably pleated gown beneath a chiffon cape that rode high on every breeze. She was singing "Free 'n' Easy," low key. Close your eyes and she was totally immersed in the song; open them and she was totally preoccupied with the gown, playing with it, studying the effect in two television monitors.

The orchestra moved into "Cry Me a River." She sang it with heart and gut, and with her eyes fixed on the monitor, holding a sparkling lavaliere at her waist, at her bosom, at her shoulder, pondering each effect intently. Then she retired to her trailer to choose a gown for the second half of the show.

"What am I going to wear?" she said, glumly eyeing two gowns, a sequined Galanos and a flowered Brooks. "Marty, [to her manager, Martin Erlichman] they've got to give me another light up here. I can't see the top of my head in the monitor. My face loses proportion. Fred [to her hairdresser, Frederick Glaser, who stood with several hair pieces at the ready], my hair isn't right this way. Let's try it with the part in the middle, huh? Marty, I saw a new angle on the monitor we never used before. It's this way, three quarters to the left [assuming the angle in front of the mirror]. It's good, huh? ...Listen, what the hell am I going to wear?"

She changed into the Brooks and went back to the cameras. "Barbra." The director's voice, coming from the mobile unit parked nearby, blasted over the loudspeaker. "Barbra, I love that one, dear."

Miss Streisand seemed to sniff the air suspiciously. "Better than the pink one?" she asked.

"Yes, I think so."

She looked momentarily confused. "I want to try on some others," she said. The director suggested they finish rehearsing first.

At midnight the orchestra quit, and she went to the mobile unit to see the tape. "Um, pretty," she said, watching the pink pleats float. "But I hate my hair like that. How about you, Elly?"

"I like it," her husband said.

"Yeah? How much? Not too much, huh?" And one was reminded instantly of that sweet one-liner about the mother who buys her son two shirts; he puts one on, and the mother demands: "What's the matter—you don't like the other one?"

He would like to see her hair worn that way for about ten minutes on camera, Mr. Gould said.

"Whaddya mean, ten minutes? Listen, if something's great, it's great for a whole hour. So you like it or you don't."

Mr. Gould stood on his judgment.

"What about the pink gown?" she asked wearily. A sticky silence. A technician spoke hesitantly. His colleagues had taken a poll, and six out of eight didn't like it. Abruptly Streisand exploded. "You know what?" she said. "I'll tell you what. You guys don't understand fashion."

The concert drew 135,000 people, the largest crowd ever assembled in Central Park for an entertainment event. They screamed, they whistled, they begged for more, but they were orderly enough. "Barbra's crowds are always orderly," someone said to a worried police captain. And Keith Robinson, 17, of the Bronx, said: "It's the way she conveys emotions. She knows what the words mean." And Theo Capaldo, 18, who had made the pilgrimage by bus from Methuen, Massachusetts, said: "When she sings you want to thank her for saying everything we can't say."

The teenage ecstasies were predictable, but the relevant point is that she wore the pink dress and it was a smash. Standing on the stage with her arms flung high, all that rosy yardage making a triumphant life of its own around her, she looked rather like an updated Winged Victory, which may have been the whole subliminal idea.

"I'm usually right," she said placidly a couple of weeks later. "It's my instrument. I've always had it."

She was lolling by the pool of her rented home from home, a modest mansion in Beverly Hills. Mr. Gould was in New York, working. Miss Streisand's house guest and closest friend, Cis Corman, the wife of a New York doctor, sat nearby reading a paper and Jason lay in his carriage. A nice little baby, blond and slender, with no marked resemblance that I could see to either parent. ("You don't think so? Oh, he looks just like Elliott. Everyone says so.")

It was a Sunday, which is a good day for Miss Streisand. She hates to work - at least she says so, and probably believes it. The eye makeup was off; the feet were bare; she was pleasantly unkempt in a cotton shift. She was feeding Jason.

"This kid is not to be believed," she said. "You should hear the doctor. Usually they start crawling for a month already. Like a snake, he crawls. Let's see, now" — aiming a tiny spoonful of mashed potatoes at his mouth — "this is the first time he's had mashed potatoes." Jason dodged the spoon and began to cry.

"What's the matter, baby? What's the matter? Yum, yum, it's good, come on, try it ... come on, little boy!" Jason declined, and she leaned back to talk on lazily about herself.

"When I was a little kid, four or five, I would listen to people talking and I knew they were missing each other. I couldn't tell them, but I understood it. I've always understood ... something or other. The realities. I sense when people are coming on, or someone does a dishonest thing, or I walk into a room and something isn't right. I ... get it."

Two years before she had told me, "It's like a guy says, 'That couch should be red,' and boom - I'll know it should be white." And no power would have convinced her that anything but white could do the trick. Miss Streisand was not then one of the great compromisers, nor is she today, but two years have done their job.

Now, she said, "I have to compromise — a little. I know that now. I've even come to understand that a little bit of compromise is part of the perfection. Know what I mean? A little bit of imperfect is part of the perfect, because perfections is lifeless and dull." Then she held her thumb and forefinger out, with a scant inch of space between them. "But just a little compromise," she said. "If I don't feel it's right — forget it."

Right. It is the biggest word in the Streisand vocabulary. To be right is not necessarily to make sense on anyone else's terms but to be true to her inner vision of how she should look, behave, perform.

And now she went on: "But I've got so many ... contradictions. At the same time that I'm so particular, I'm lazy. I used to want to be a ballerina. But I could never devote my life to all that practicing. Besides, I wouldn't want to hurt my toes. [It is an aside, thrown in to disarm.] Singing, funnily enough ... you build up muscles in the throat and diaphragm that make it easy. But once you stop singing, it goes. Then it's damn tough to get back.

"But if something has got to be, I can do it. Like if the high note is right for the song, I can reach it, because that's the way it's got to be. There's always a way it's got to be. It has nothing to do with the technical details. It's a right way, an honest way. Like I've got this scene where I'm supposed to be a little girl, and they wanted me to wear a bow in my hair. A bow! I mean, if I can't play a little girl, I'm in the wrong business. What's a bow got to do with it? It's what I do that makes it work, not some damn silly bow.

"I used to have just the instinctive reaction — this is right or this is wrong — and I couldn't tell why. Now I can tell why. And I'm in a position where I could easily say, 'No. Not this way.' But I hate to. It's much more satisfying to work with someone who ... gets it. Someone who sees it my way or can prove me wrong. I want to work with someone who can prove me wrong. [The intimation here is that it hasn't happened often; and in fact, it hasn't.] It saves a lot of time.

"I always want to push right through to the basics. Sometimes I don't like myself for being so ... basic. I feel maybe I should be more — you know, make the small talk, be more outgoing and all that. But it wouldn't be me. I can't cope with 'You look lovely today' or 'What a pretty dress.' It makes me uncomfortable. If I dislike someone, I can't hide it. If I think an idea is lousy, I have to say so. I need someone strong to bounce off. What I hate is when I'm singing and everyone just sits there, smiling and nodding, uh-huh, uh-huh ... Listen, is it good, is it bad, what is it?"

The next morning she was on Stage 12 at Columbia, wearing pink tights and tutu ("Ballet is so full of clichés. Why do the tights always have to be pink?"), waiting to rehearse a number called "You Gotta Have a Swan." It is a parody on Swan Lake. Prince (boy dancer) threatens to shoot swans (six girl dancers), Streisand (playing Fanny Brice playing Swan Queen) defends them in song and dance.

Earlier the song had given her trouble. "It doesn't feel right," she had complained to Herbert Ross, the film's choreographer and director of musical numbers. "I'm standing here singing this funny song and I have nothing to act."

How did she feel about the prince? Ross asked.

"I hate him," she said, "because he wants to kill all those beautiful swans. What the hell does he want to do that for? He must be dumb." Thus she had found an attitude: contempt for a dumb prince. Now she was improvising completely: Streisand stands guarding her swans, arms protectively spread-eagled, gazing with hauteur at the prince. "Vat you gonna do?" she says, her pink tutu giving extra zing to the pungent ethnic flavor of Fanny Brice. "You gonna shoot des svans? Dese lovelies? Vat are you ... dumbness? Oooooh, are you a dumbass?"

"Wait a minute," Ross says, "Barbra, why not use the word 'dumb'?"

"Because it's dumb," she says. "I like dumbass or dum-dum, but not dumb." Ross nods - they are on a felicitous wave length ... and Streisand proceeds:

"You're some kind of a nut, maybe? These beauties are mine, twinkeltoes; [smiles tenderly at a swan.] Show him your twinkle, sweetie."

The prince crouches fearfully. "Come here, Prince," she says. He take a glorious flying leap. Streisand shakes her head disdainfully. "You had to do dat, heh?" she says. "I mean, you couldn't just walk over like a poyson?"

The dancers break up. Ross roars, "Great line," he says. "Remember it!"

"Yeah, sure," says Streisand, grinning. Then: "What was that line again?"

At the lunch break a local jewelry salesman appeared on the set with sample cases. The girls clustered around him, Miss Streisand in the forefront. "How much are those?" she said, pointing at gold earrings. "What! Twenty-four dollars? Hah! I buy the cheap ones for two dollars and they look just as good. Now, that's cute [indicating an enormous amethyst and diamond ring]. Lemme see it. How much? Five hundred! Listen, I got the original that this was made from. It cost me ... two hundred and fifty!" This was the Brooklyn Streisand, which she can put on and take off without a strain. She was playing to the dancers and they were loving it.

"Here, lemme see that ring ... Wait! I need a loupe."

The jeweler handed her a loupe, which she fixed to her eye like a veteran. "Nah, these are all new diamonds. Mine are old diamonds. They're better, the old diamonds.

"Listen, I got one of these loupes in solid gold. Yeah. Elliott had it made for me. It's got engraved on it, 'Look but don't buy.' Yeah, it's true. I swear it."

A nurse appeared, carrying Jason. Miss Streisand has him brought to the studio often; he sleeps in her dressing room while she works. She took him from the nurse as he cried, peering at him with huge pleasure. "Hel-lo, baby. Hel-lo. Oooh, what's that, that crying? What does that mean?"

She fed him in her dressing room, and emerged with him a half hour later as her soundtrack recording of "People" was blasting from the studio, concentrating intently upon the sound of her voice; and all the while she held the baby close, murmuring to him and burping him repeatedly.

"She thinks," Ray Stark, the producer of Funny Girl, said later. "Even when she's burping the baby, she's thinking. That little IBM machine is ticking away."

Several days later Miss Streisand was back in the studio making costumer color tests. In an orange traveling costume and a sable hat she posed to the left and to the right, sneaking glances in a long tilt mirror. Costume designer Irene Sharaff prowled the set like the Dragon Lady, darkly surveying her handiwork.

"These earrings are wrong," said Miss Streisand. "I look like a gypsy. They should be long and straight." She pulled them off. "Irene," she said, pointing to the belt, "this isn't the right brown."

"Yes it is, Barbra," said Miss Sharaff. "We went to a lot of trouble to match it. It's exactly the same as the shoes."

"Yeah, I know," said Miss Streisand, "but it's not the same as this." She was pointing to her hat, the dark ridge of fur in her sable hat.

"She's always been terribly intelligent about herself," says Herbert Ross. "The first time I met her, at the Wholesale auditions [Ross choreographed I Can Get It For You Wholesale], she came in wearing an unbelievable raccoon coat and she never stopped talking. It had to do with not having an apartment and sleeping in somebody's office, and it was all very funny and original.

"She was very unselective in those days. She'd give you twenty ideas without knowing which was best. Now, of course, she knows."

Certainly, at 19, singing in supper clubs, she must have been working out of intuitiveness when she transformed such stand-bys as "Happy Days Are Here Again" into ballads of bitter irony.

Her birth in Brooklyn, and not, as they say, into money; her exodus across the vast chasm to Manhattan; he wandering about the city, dressed in traffic-stopping relics of the 1930's, demanding to be noticed until finally she won a Greenwich Village singing contest — all have been amply documented. "Sure, it was the way I wanted to look," she says. "A defense, maybe, against feeling not pretty. But it was also the dramatically right way to look. I knew it." This was at 16.

"When I first met Barbra in acting class, she was fifteen," says Cis Corman. "But there was nothing remotely adolescent about her, even then. She's grown, of course. Her taste is better; she's seen more, done more, lived more. But all her qualities were there to begin with. She already knew her mind. Ten people could say, 'Gee, do you really like that dress with the buttons down the front?' and she'd say, 'Yes, I do.' When she got her first apartment, over a fish restaurant on Third Avenue, the first thing she bought was a marvelous old Early American desk. [It still sits nostalgically among the Louis Quinze splendors of the Gould's duplex apartment on Central Park West.] I mean, who even knew what antiques meant at seventeen? I didn't. She hung a beautiful gilt picture frame on the wall and arranged old beaded bags around it. There was no picture in the frame, but the composition was beautiful."

This is an interesting thing, this preoccupation with the old and the handmade. Shortly after returning East I was rummaging in an antique shop one day and came across an ancient, rather worn beaded bag. On impulse I bought it for her. It cost $12. A week later she and the film company were in an abandoned railroad station in New Jersey, filming location shots — her first actual work in front of the camera. I gave her the bag there.

Later she said: "People just don't understand. Why do I look for months for a little beaded bag that it took some guy so long to make? Today they make it overnight. You press a button and it's made. Is it better? No. It's faster, easier, duller. Life is duller. The human element is gone."

She was serious now, groping to voice thoughts she has voiced often before and which some critics with college degrees and tin ears — Miss Streisand has neither — have put down to intellectual pretension. "In every art, only the things that have some tangible part of oneself are moving. Not the technical things, but the what of oneself that went into it, the feeling. Like in a painting, what moves you is what the guy felt - and how do you describe that? Is it that red dot over there? Whatever is in it of love, and thought, is the immortal part. It doesn't die. It doesn't decay.

Then she went back to work, repeating endlessly a scene that might take 30 seconds' film time - Fanny Brice getting off a train and being greeted by news photographers. Swathed in furs beneath the stifling lights, she descended the train steps again and again, each time smiling stiffly for the photographers. "Hold it, Miss Brice." Finally, inspired perhaps by sheer boredom, she made a sudden funny gesture, not remotely in the script. She came down the steps, turned her face full into the phony smoke that was billowing up from beneath the vintage train, coughed hard, fanned the smoke away and made a disgusted face.

Everyone was enchanted. First film, first scene, who'd ever heard of such spontaneity? Miss Streisand herself was nonchalant. "What's the big deal?" she said. "Why should anything change just because the camera is on? It was honest, wasn't it? There's smoke - you cough."

There was a consensus that she would be quite a movie actress. She herself, of course, was already thinking about being a director. She would say nothing more about it - simply smiled, obviously savoring the thought with immense pleasure, almost lust, and repeated, "Yes, I'd like to be a director."

I recalled that she had once told me: "What do I want? Everything. I'd like to win the Tony, the Emmy, the Grammy, the Oscar — all of it. Maybe someday I will."

Today she has four Grammys (record-industry awards). Her first television show, My Name is Barbra, picked up five Emmys. She has won two Tony nominations, for I Can Get It For You Wholesale and Funny Girl. As for her Oscar, I strongly suspect it is only a matter of time; and so, in all probability, does she.

END

Page credits: Silvio Palmieri provided the cover scan.

Related Links:

[ top of page ]