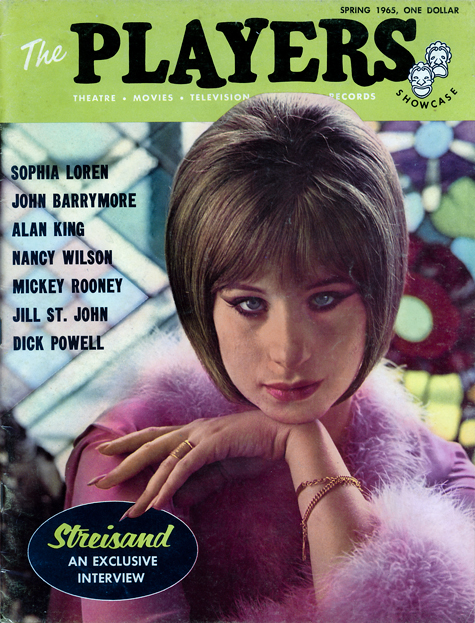

Players Magazine

Spring 1965

Streisand: Happy Days Are Here (At Last)

by David Henderson

(cover photo: Milton Greene)

Part One | Part Two

PRESENTING PART II OF BARBRA'S STORY, THE PLAYERS SHOWCASE FINDS BROOKLYN'S FORMER “BORN LOSER” SITTING ON TOP OF THE WORLD.

ON THE MEMORABLE evening of March 26, 1964, the world suddenly changed for Barbra Streisand. Prior to that spring night, the "Brooklyn Nightingale" was just one of eight million people who belonged to greater New York. But from that day on, New York belonged to her.

The change was wrought, of course, by her opening night triumph in Funny Girl, which instantly etched her name on the bronze tablet of immortality. That night she said, "Here I am, world," and it seemed as though she had been there all along.

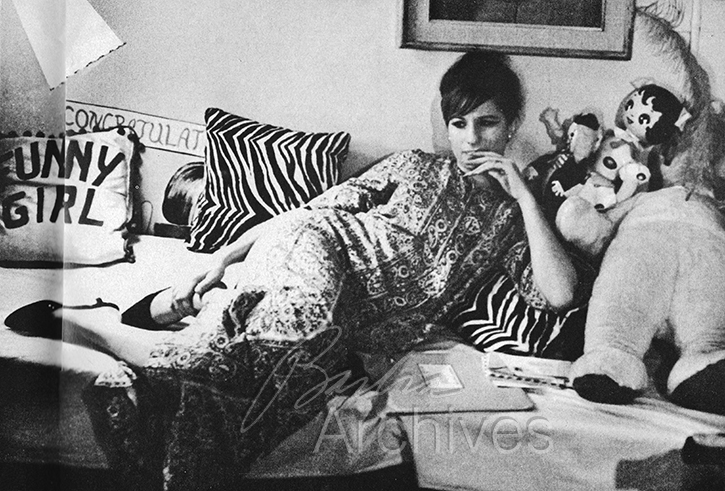

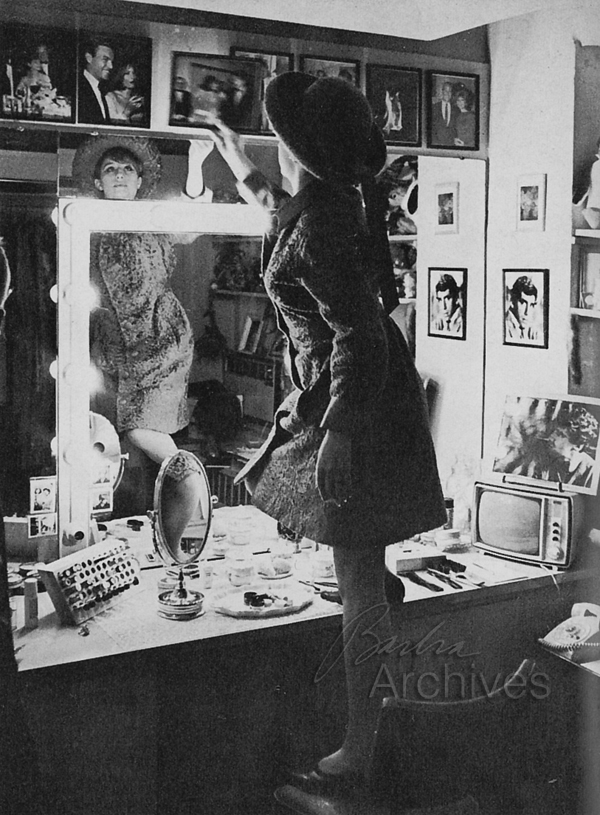

Pondering answer to interviewer's question, Streisand relaxes in dressing room

among stuffed toys presented to her by fans.

What is it like to ride the crest of onrushing success, especially after one has shed tears and sweat to get there? Is it all joy and sweet comfort?

I was pondering the question of how success was treating Barbra Streisand while walking along Seventh Avenue on the night before our interview in her dressing room. I noticed the usual crowd clustered around the stage entrance of the Winter Garden Theatre across the street. A limousine was waiting at the curb, so I stopped. The stage door opened, and Barbra came out. She walked hurriedly through the crowd, glancing politely to the right and left, but aiming steadfastly for the refuge of the car. In an instant, the limousine was merging into the current of traffic. Standing next to me, a woman—obviously an out-of-towner—turned to her husband. "Who do you suppose that was?" she asked. "Don't know," replied the man, unaware of the three-foot letters spelling Barbra's name on the back door marquee. "Maybe a movie star or something."

Here was a contrast. On one side of the avenue, there was a silent crowd of worshippers who would idolize Barbra Streisand; and across the street, two people who had not the slightest idea of who she was and did not care to find out.

So this is fame, I thought. Some people really flip; others don't give a hoot. But with Streisand, it is not just a matter of being interested or disinterested. With her, the division often is much more sharply divided between those who adore her and those who "can't stand her." Why?

Several reasons. For one, she has hit stardom so rapidly that people only know who she is, not what she is. They form opinions from what they read in the newspapers. It then becomes very easy to get the wrong impression of her, because her personality has more facets than a diamond—and each glitters in turn as you point different sides of her toward the light.

Also, as mentioned in Part I of the Streisand story in the last issue of The PLAYERS Showcase, she is "a strange entry in the tinseled universe of show business." She is unique, and many people interpret that to mean she is vulnerable; so they adopt a rather protective attitude. Others do not understand her, and they do not like what they cannot understand. They label her as a "kook".

I asked Peter Reilly, a sharp, friendly young man who handles publicity for her recordings at Columbia, whether he regards Streisand as a kook. "Well, she's no kook," he replied. "She once said to me, this whole bit about thrift shops, and so forth, has been put all out of proportion. And she brought a pair of shoes and said, 'See these shoes? See the way they are made? They don't make shoes like this anymore.' You know, she was impressed by the quality with which they made the shoes. At the time, she did not have the money to buy from expensive shops, so she bought what to some people may seem kookie."

Some reporters have privately expressed the idea that Barbra does not seem very bright since she does not field questions with fast answers and witty remarks. But Reilly has worked with Barbra since she recorded for Columbia with the original cast of I Can Get It for You Wholesale. "Barbra is intelligent," he told me, "one of the most intelligent performers I've ever met. She's one of the performers who, really—you can almost see her learning. A lot of performers come on, and they do their acts. But Barbra really learns from each performance."

If she does occasionally lack sparkle in her dialogue with reporters, there is a simple reason for it. She says interviews are weird. That is another way of saying they make her nervous.

At the age of 22, Streisand is hardly a seasoned veteran of show business. And the suddenness of her success, which makes her adjustment to her new life more difficult, shows through in her conversation.

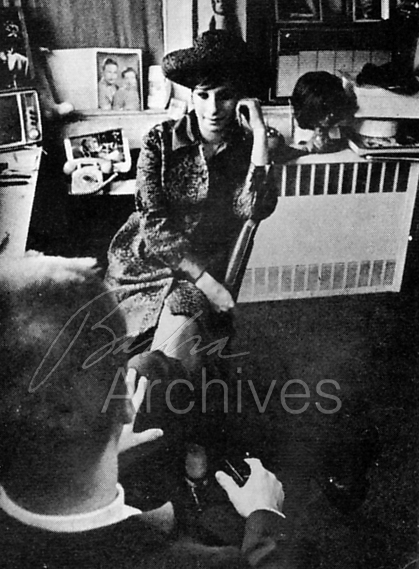

I waited for Barbra in her dressing room at the Winter Garden, chatting comfortably with a pretty, taffy blonde named Eileen Peterson, who handles Barbra's public relations through the New York office of Sorters, O'Rourke, and Sabinson, and with Frank Eck, The PLAYERS Showcase photographer. When Barbra entered, she glanced quickly at us, said "Hello" quietly as I shook her fragile hand, then proceeded between us into the adjoining room, which contained her dressing table and closet. She was polite, but very distant.

I followed her with cordial remarks and compliments on her performance the previous afternoon. I said it was great, and meant it. But she didn't loosen up. Instead, she climbed up on her chair and took down a picture of her husband, Elliott Gould, the handsome leading man she had met in Wholesale. She was looking for a better place to put it. Also, she was looking for a place to hide her nervousness.

For several minutes, she continued to rearrange pictures as she would the pieces of a puzzle. In her hand, she held a framed photo of the late President Kennedy, with her standing beside him. And there was that famous scrawling signature following his "warm regards. . ."

"What was it like," I asked, "giving a command performance for the President?" "Very, very thrilling," she said. "He was. . .the most exciting personality I've ever met."

She sat down suddenly, and we talked about Brooklyn. Our conversation was quiet, and I could hear the frequent click of Eck's camera. "I'm glad I came from Brooklyn," she disclosed. "But I'm glad I don't live there now. You know, once you cross the bridge, everything changes."

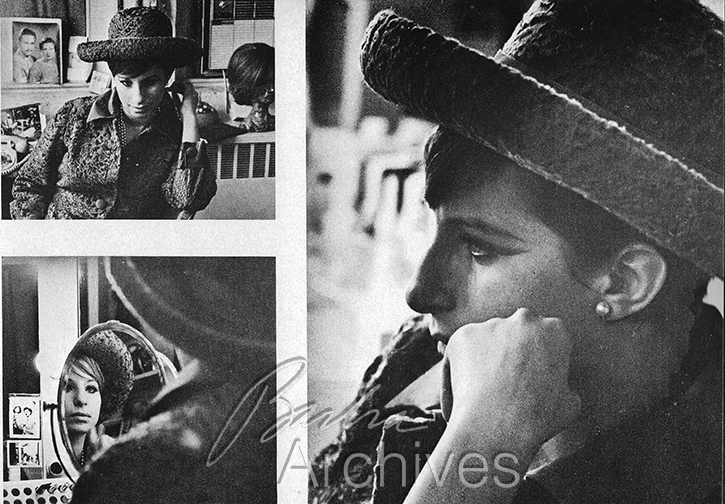

She had not yet removed her coat and hat, which were of matching gray and charcoal broadtail fur, and typical of her preference for rich textures and subtle color combinations. Now she asked to be left alone briefly while she put on something more comfortable.

The something comfortable, it turned out, was a neck-to-ankle sheath robe in a startling Victorian print which—suggested Eileen—"makes you look like a serpent." The comment triggered a slight, gentle laugh, and Barbra— curled up on her day bed among stuffed animals, dolls, and satin pillows—went into a form of relaxation that bordered on exhaustion. The strain of doing eight shows a week—plus meeting countless obligations, from giving interviews to ordering new fabrics for her apartment—was taking its toll of her energy. Another penalty of success.

I said, "Your success probably seems like the result of a long, graduated ascent. But the public seems to think that you arrived on the scene very suddenly. What is your view?"

There was a long silence. Then: "It's funny, it's like. . .the most difficult, the most radical changes happen when you're young. It seems like you've lived through five generations, five lives, because by the time you're 20, you've done so many things. After you're 20, the changes are fewer, over a longer period of time: When you're growing up, everything is so radical . . . it's like if my success just . . .when did it begin? When did I want to be an actress? When did I finish being a child?"

"You don't actually recall when it was that you decided this is what you wanted?"

She rested her chin on her thumb, lightly. "I wanted to be a star (she pronounced it stah) when I was 14— but that's eight years ago, you know. When I first, uh, professionally earned money, that was four years ago. That was quite a period of time. I mean, I grew up." She paused, stopped talking to the room, and looked at me. "Nothing is overnight, you know?" she said, watching me nod in agreement. "I got great reviews when I sang, when I first opened up. But I didn't have anybody banging on my doors, giving me offers."

"Well, you do now, and I imagine it has made quite a difference. How do you feel about your success?"

"I constantly get buffed back and forth in the way I feel," she said. She sat up a little straighter. Her gestures seemed a little more animated. "It's like—like you know, coming up here tonight. There's this boy out there, with all those kids who are waiting at the stage door all the time, and this boy says to me, 'Is it all right if I come up and watch the interview?' And I said. . . 'What did you say?' And the kid said, 'Can I sit and watch?' And I tell you, I couldn't answer him! It was so sad. I mean. . .can you imagine a kid saying that? If everybody asked me if they could come watch—if I let everybody watch me—all of a sudden, it becomes. . .just impossible, just so ridiculous. . ."

Downstairs, in the hollow theatre, someone was warming up a clarinet. The sound entered Barbra's dressing room through the intercom. In a couple of hours, it would blend in with the orchestra, striking up the overture for a fur-clad and jewel-bedecked audience that would be bristling with anticipation. I remembered the excitement at the matinee performance the day before. Jam-packed. It was a holiday, and there were a lot of teen-agers in the audience, but they were no more enraptured than the adults who were practically on the edges of their seats, waiting to applaud Barbra when she finished the song that was stirring their emotions: "Don't Rain on My Parade."

It was during the curtain calls that the youngsters in the audience could no longer contain themselves. They rushed down the aisles, pressed against the orchestra pit, jumped up and down, trying to get a better look at the star. Some of them stayed there even after the final encore, thoroughly spellbound.

I mentioned it to Barbra. "Does it disturb you when teen-agers watch you so closely, express their devotion so openly, and emulate every move you make?"

"Yeah," she replied. "When they do it in the theatre, I don't mind it, but when they do it in the street—you know, they follow me around, to my house, and they leave presents, and it is frightening. When I was waiting for the cab the other day, this kid put his coat in the gutter for me to walk on—you know, in the guttuh! And, well, I didn't want to walk on his coat and told him to pick it up, and it happens often, you know. And another time, they gave the cab driver a dollar, wanted to pay for it.

"It's insane. You can have people who love your work, have respect for you. But not your whole life. I brought this up for one reason—the frightening bit, you know—because it's, like, inhuman. And anybody's human, who is a personality. Now, all of a sudden the image becomes more important than the person. You know, the symbol is more important than the flesh and blood. And it puts you on a spot. Everything you do can destroy the image, 'cause I'm only human. I can never live up to their symbol—and yet, they pretend they do want to get to know you. But if they ever knew you—well then, you'd be like everybody else, mere flesh and blood, which they don't want. . ."

It was time for a lighter subject. I asked, "Where do you think you'll go, after Funny Girl?"

"Home—and sleep all the time." She feigned exhaustion, and we all laughed.

"How about singing in clubs? Would you like to go back to that?"

"No. I'd like to do concerts. Oh, and I have a TV special coming up in April."

"Many of your fans are not aware of your talents as an actress and comedienne. I think it would enlighten some people, outside of New York, to see you performing in a role."

"Yes," she said, "that's where the movies come in ... playing in small towns."

"You know, your ambition was to become an actress, and your singing just. . ."

She interrupted. "That's funny. I mean, you know what you just said? 'You know, your ambition was. . .'" She had imitated my voice, and we chuckled. "And it's almost like," she continued, "like—gee, everybody knows that! That's funny, isn't it? Who would think that people would know all about you?" She was genuinely amazed.

"What kind of relationship do you have with the cast in Funny Girl?" I asked.

"It's funny, I'm the youngest one in the cast, and it's like I'm their mother and I'm their child."

That amused me. It was somewhat the same idea expressed by her director, Carson Kanin, when I asked him that question. Kanin is an extremely kindly and busy man who works in a large, barren office overlooking Broadway. There are no curtains or rugs, not even a fancy desk. Just broad wooden tables, straight-backed wooden chairs, and walls of books. His office is free from pretense, a place where a man proves his genius by thinking and creating. Kanin fits into this office well. Grey-haired, sharp-eyed, thin, dressed in a woolen sport shirt with a knitted tie, he immediately impressed me as a man who doesn't have to kid anybody. I liked him when he first greeted me with a warm smile. And I liked him even more 20 minutes later, long past the 10 minutes he had allotted me, when his Hubert Humphrey voice continued to discuss Barbra Streisand. . .

". . .And she just came up with her part at the right time," he was saying. "If I had a second choice right now, I don't know anyone else who could play the part."

"Did you audition anyone else?" I asked.

"No, as a matter of fact—although she wasn't signed at the time I came into the show, I knew she was the one they all wanted, and I couldn't think of anyone else who could have done everything that was required. So it was all just one attractive package, and she certainly was marvelous from the word go. Never stopped working, never stopped trying to perfect her role."

"Was she difficult to direct?"

"No, you see—my method in directing her was to attempt to get her to realize all those important facets of her own personality. The riches that we had were a unique personality, and she knew more about that than anyone ever would—could possibly ever know. What we had to do was free that, create an atmosphere in which her own personality could flower."

Her stage stardom, Kanin explained meaningfully, is not limited to Funny Girl. He said he would not at all mind directing her in a straight dramatic role of some kind.

Barbra indeed proves herself an excellent actress in Funny Girl. And an excellent comedienne.

In her dressing room, I asked her: "Is there anything you'd like to explain, about the kind of person you are, that hasn't been covered?"

There was a long silence. Then she said, "All I can say is that I'm not totally attracted to the idea that people want my autograph, you know? It seems to me that there are two totally separated kinds of categories—when I perform, and when I'm in their lives. And when they start to mix, I can't quite. . .figure it out. So I don't like to sign autographs. It's just a weird thing to me, a weird feeling. I would just like to be admired on the stage and then left alone in life, but it's impossible.

"And I guess having this success quickly, and being young, does that. Because it was not long ago when I was struggling for money, and I couldn't afford taxi cabs, and you know, I didn't have a place to live. So, to make that adjustment all at once—you know, I'm still the other girl, the one who's looking for the bargains, from the people who used to give me discounts. Now, all of a sudden, it changes. But I haven't changed. Their attitudes towards me have changed, but I haven't changed. So I have to realize that their viewpoint of me is different now that they think I'm very rich and — it's a helluva thing."

So this is fame. You take the bad with the good. You gain some comforts, you give up others. But I learned something else; Barbra would not give it up for the world. The closer it got to show time, the more she came alive. In a little while, she would be standing in the wings, waiting for the orchestra to finish the overture, waiting for the curtain to come up. Then she would walk calmly onto the stage. She would pause at center stage and gaze out over the footlights at the audience, and receive her applause. Then she would cross to the left, take her seat at a dressing table, pretend to gaze into a mirror, and say again the line that opened so many previous performances, that has been quoted almost as often in the press: "Hello, gorgeous."

I got up to leave. Barbra would now have to start getting ready. I said thanks and shook her hand. Her mind was already drifting into that other world. Earlier, she had been talking to me like an old friend, mentioning things about Part I of The PLAYERS Showcase story, and quoting a couple of lines verbatim.

Now, in her expression, I could see I was a stranger. I clattered down the iron stairway and slipped out through the stage door. The crowd was still waiting. Some faces were new, some had been there when I arrived. All those people, waiting forever for the star!

Indeed, Barbra Streisand is a star, I thought as I headed back to the Hotel Americana. And yet, that star I just talked to is also a human being.

End.

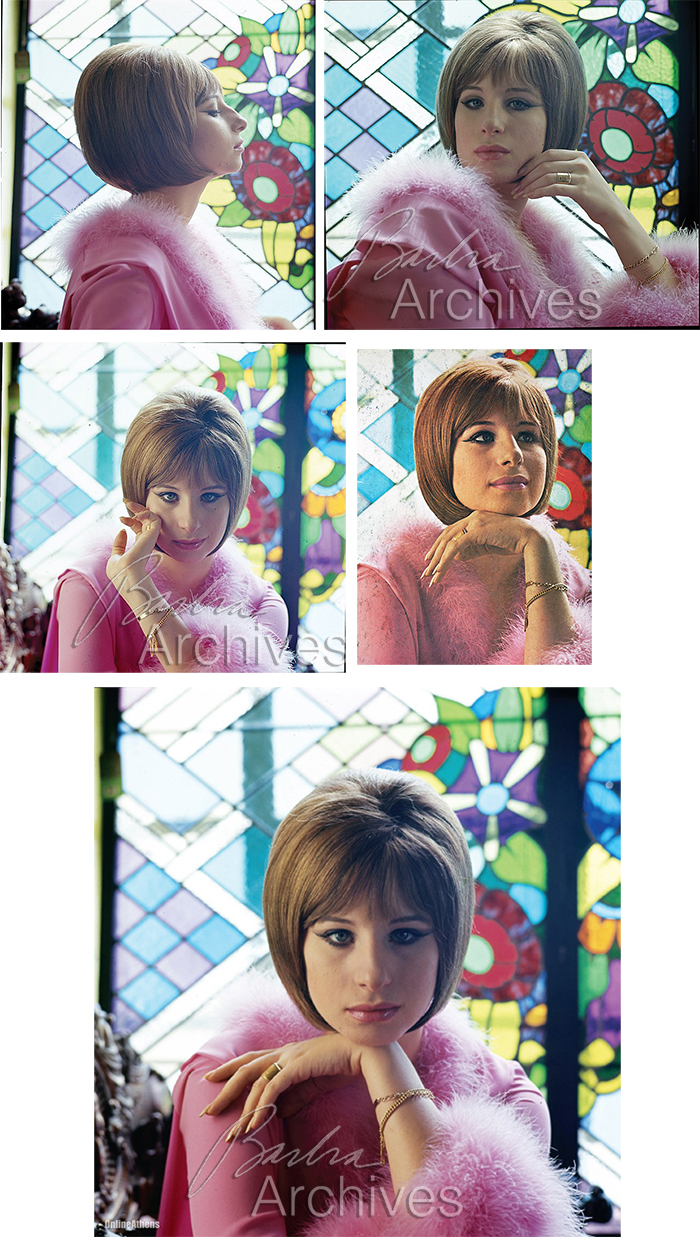

Milton Greene Outtakes

[ top of page ]