Pageant Magazine

November 1963

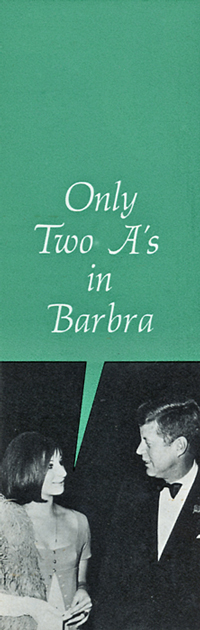

Only Two A's in Barbra

by Norman M. Lobsenz

She's not pretty. She wears dresses that make her look pregnant. And then the kookiest girl around belts out her songs.

THE GIRL in the sleeveless black blouse, striped white slacks, black moccasins, and strand of rosy-pink pearls picked up the phone in her hotel suite and asked for room service.

"I've gotta go on a diet," she said to me. "I'm gonna have what the menu calls a 'physical fitness special' . . . . Hello, room service? What's this 'physical fitness special'?' ... Uh-huh ... uh-huh ... well, send me instead a stack of pancakes, half a dozen strips of crisp bacon, and lots of butter, syrup, and milk."

She hung up and gave me a charmingly lopsided smile. "I can't help it," she shrugged. "Pancakes are my favorite food."

"It seems to me," I said, "that you've told other people something different. At various times you have claimed your favorite food was crabs, watercress, and broiled mushrooms."

"You want to know something," the girl said, "my favorite is really artichokes. But I can never find the heart. It's hidden under all that fuzzy stuff. Anyway, I love all food. People ask me what my goals are, but I don't have any big philosophical goals. Mine are more sensual and short range, like: When am I going to eat at Le Pavillon?"

The girl, Barbra Streisand, can eat at Le Pavillon—one of New York's outstanding (and expensive) gourmet restaurants—any time she chooses. Which is one way of measuring the astounding success of the 21-year-old singer-comedienne who only a few years ago was going without lunch to save money.

Another way to measure her success is to tick off her accomplishments from the time she turned professional little more than two years ago. Since then: She has been the hit of one Broadway play and has been signed for the title role in another about Fanny Brice, scheduled for this winter; she has made dozens of television appearances on the Tonight Show, the Ed Sullivan Show, and with Garry Moore, Dinah Shore, and Bob Hope; she has been chosen to entertain for President Kennedy at a White House dinner; and she has cut a phenomenally successful record album, and her second, typically titled The Second Barbra Streisand Album, will be out just about now.

She has also become a headline performer at some of the nation's most important nightclubs: Basin Street East in New York, Mr. Kelly's in Chicago, the Riviera in Las Vegas, Eden Roc in Miami Beach, and the hungry i in San Francisco. She had an early October date to appear in the Hollywood Bowl. Around her has grown what columnists refer to as the "Barbra Streisand Cult," a group whose stage-wise members range from Broadway director George Abbott to songwriter Harold Arlen to novelist-playwright Truman Capote.

Perhaps even more important are the raves she gets from hard-boiled critics of the entertainment trade press. When the musical comedy I Can Get It For You Wholesale opened on Broadway in 1962, the show itself drew mixed notices. But every one of the reviewers singled out Barbra for special praise.

"Great .. hilarious . . . spectacular . . . a natural comedienne," were some of the comments. Variety called her a "cameo-faced chantootsie with a warm and sharp set of pipes." Billboard flatly predicted that she "is headed for stardom." And another critic, describing her as a combination of Judy Garland and Audrey Hepburn, simply said that she was "the best young singer in the U.S."

Barbra, incidentally, is correctly spelled without a middle "a." She dropped it originally because she hated the name "Barbara."

"I think I'll gradually cut the whole thing down to just 'B,'" she told a reporter recently. "Anyway, I sometimes call myself Angelina Scarangella, so what difference does it make?"

Barbra has a lot of trouble with copy editors who keep putting that "a" back in. Not long ago one writer devoted a whole column to Miss Streisand's battle for noinen- clatut'al uniqueness. A week later he wrote another column about her in which she was unvaryingly called "Barbara." "Oh, well," says Barbra, "Katharine Cornell, a great actress, fought for thirty-five years to have her name spelled correctly, and most of the time it came out 'Katherine.' "

BARBRA MADE her unheralded debut—"I was sort of the third act on a two-act bill," she says —at Bon Soir, a nightclub in New York's Greenwich Village, at the age of 18. Although she had been studying acting, she preferred to sing. One night she won an amateur song contest in a neighborhood bar. A friend in the entertainment business suggested that Bon Soir audition her.

"I really didn't know what I was doing," says Barbra. "For one thing, I wore a costume made up from my collection of ancient clothes I buy in thrift shops. I like to buy clothes in thrift shops. Why pay seventy dollars for something you can get for two dollars if you don't mind it's been worn once or twice? And the salespeople are nicer.

"Anyway, here I was in an old long black dress, a kind of Persian vest, and a pair of big white shoes with thick heels and a buckle on the front. I had gum in my mouth. I decided the first song I'd do was one I'd never done before. It was 'Keepin' Out of Mischief Now,' by Fats Waller, and the club pianist had never even played it before. When we were getting ready to begin, I'd keep saying, 'What's the first note?' Where do I come in?' Things like that. They loved me, I don't know why."

Barbra still wears kookie clothes on stage. "Most girl performers follow a standard pattern of dress," Barbra says. "It's satin sheaths or beaded gowns and long white gloves. And they're wired to look sexy, only they don't look sexy, they look ridiculous. I like to wear long, full, Empire gowns. Or tents even. So people start to whisper, 'She's pregnant.' This is logical? This is a reasonable assumption—because I wear an Empire gown I'm pregnant?"

Barbra was married early this year to Elliot Gould, who starred as the double-crossing garment-district operator in Wholesale. A few weeks after they were married, Gould flew to London to be in a play there, and Barbra's married life has consisted largely of airmail letters and transatlantic phone talks.

In one way, however, she considers herself fortunate to be married at all, for her physical appearance has always been the butt of sharp-tongued wits. Barbra's face, for example, has been described as resembling that of an "amiable anteater" and a "sour persimmon." She has, one critic wrote, "haystack hair, a beanpole figure, and she lopes like a camel with a snootful." Said another, "Barbra Streisand has tiny eyes close together, a long nose and pointed ears." New York Times critic Howard Taubman described her as "a girl with an oafish expression, a loud irascible voice and an arpeggiated laugh."

"I hate these descriptions," Barbra says. "I'm very sensitive to them. I know I'm not beautiful, but many people in the art world think I have marvelous features."

Perhaps partly because of this sensitivity, Barbra, in an almost self-consciously nonconformist way, sings songs no other performer would dare to try. "When I got my first club job," she says, "I had to put an act together. I hated mushy love songs. And every other singer always seemed to be doing the same hit numbers from the same Broadway shows.

"I KNEW a guy who had a big collection of old seventy-eight r.p.m. records from the 1930s and '40s. I was looking for songs that were actable, songs that had a kind of story in them. People told me I needed chic songs, because the club was sophisticated. I couldn't care less. So I picked the silliest song imaginable: 'Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?'"

This song is now one of the high spots of her act. Barbra does it as a sort of naive narrative with a different voice for each pig, a grimace of concern as the houses of mud and straw come down, and a triumphant roar as the brick house stands firm and the wolf gets roasted in the fireplace. The sophisticated patrons of the sophisticated clubs are enraptured.

Another of her favorites is "Hapy Davs Are Here Again," the 1932 theme song of the first Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential campaign. It was a slim, trite number even then. But Barbra makes a torch song of it, singing it with a slow, intense ecstasy that does not seem at all out of place with the lyrics.

Barbra's nightclub act varies widely from performance to performance. Along with "Big Bad Wolf" and "Happy Days," her current act usually includes "Cry Me a River" and "Lover, Come Back to Me." She will intersperse a comic monologue or two, such as the one about a mythical folksong based on the story of an unhappy maiden who went down to the river to commit suicide but couldn't because the river was frozen. All of this is delivered in a perfectly pitched, beatifully controlled voice accompanied by touchingly charming and almost childlike gestures.

Barbra Streisand has been offbeat most of her life. When she appeared in Wholesale, she insisted on writing her own biography that would run in Playbill. "Born in Madagascar," it read, "reared in Rangoon, and educated at Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn . . ." The only bit of truth in that concoction was the Erasmus Hall part. "What does it matter where you are born?" she has remarked.

BARBRA WAS BORN in Brooklyn in 1942, and, she says, she did not set foot in Manhattan until she was 14 years old. Barbra's mother still lives in Brooklyn. Her father died when she was an infant, but she is devoted with an odd intensity to his memory. She is proud of ihe fact that he was a Ph.D., that he was a high school teacher, and that he was listed in a directory of "leaders of education." "I look like him," she says. "That's why I'll never change my last name or my nose."

At Erasmus Hall High, Barbra was, by her own admission, a "real misfit." "I used to run around in crazy clothes and purple lipstick. I was in all the honor classes—I had a ninety-four average when I graduated—but I looked like I belonged in the ungraded class. The smart kids wouldn't have anything to do with me because I looked like a beatnik, and the beatniks rejected me because I had brains."

After she was graduated, Barbra moved to Manhattan, shared a cold- water flat with two girl friends, and worked as a clerk-switchboard operator for a printing company. She studied acting, although she assumed her looks would prevent her from becoming an actress.

"I used to think I looked funny rather than pretty, so I sang and clowned around to cover it up," she says. "I figured I'd never get started in the theater because I wasn't pretty enough to play the ingenue parts. But is it crazy for me to want to play the love scenes? Is love only for blue-eyed blondes? What's beauty? It comes from within."

Once Barbra was interviewed by Lee Strasberg, who runs the famed Actors Studio school that teaches "Method" acting. Almost any aspiring thespian would do anything to be accepted there. But when Strasberg asked Streisand which actress she most admired, Barbra looked him straight in the eye and said: "Mae West." Obviously, she didn't get in.

After her success at Bon Soir, Broadway producer David Merrick asked her to audition for the role of Miss Marmelstein, a harried, frumpish, garment-district secretary in Wholesale. Barbra, who had an offer to sing at the hungry i, one of San Francisco's top clubs, almost turned him down.

In a sort of compromise with herself, she showed up for her audition an hour late and dead tired from being up till the wee hours at a party the night before. She sang Miss Marmelstein's lament slouched in a chair, her hair tousled and her body expressively slack. The director not only hired her on the spot, but ordered her to do the song the same way in the show.

ALTHOUGH IT IS commonly accepted that her success as Miss Marmelstein made Barbra a "star," this is far from the key to her success. According to her personal manager, Martin Erlichman, Barbra's stardom was not artificially created but "had to happen."

Well-meaning advisers were constantly telling her to change everything from her face to her act, says Erlichman. "But Barbra and I merely stood our ground and waited for her talent to speak for itself. About the only things we did in the way of what you might call 'guiding' her career was to turn down jobs that offered money in favor of those that offered opportunity. For example, we rejected an offer to play the Waldorf-Astoria last March, because we knew that the small audiences of the Lenten season would not suit her kind of act. We rejected a Chicago hotel appearance, because we knew the room was too large for her intimate appeal.

"I would say the two turning points of her career so far," Erlichman contintues, "were the success of her first record album, which gave her a national reputation, and the tremendous word-of -mouth publicity that grew from her nightclub appearances."

For example, when Barbra first opened at Basin Street East she appeared first on the bill, followed by headliner Benny Goodman. But when Barbra finished her act the audience was drained, and Goodman found her too tough to follow. So the order was changed, and Barbra followed Benny. The first week she appeared at Mr. Kelly's in Chicago, she broke the club's attendance record that had been set by monologuist Shelley Berman.

With these experiences behind her, Barbra can truthfully say she has not been hurt by her nonconformity. "A lot of people used to tell me," she says, " 'Kid, you better dress this way, and sing this kind of song.' But I think that when you ask an audience to love you, they turn away. So I dress the way I feel, and sing the way I feel, and I don't worry about the audience—not till afterwards, anyway. People say I'm fresh, because I don't take advice. But even if the advice is right, I have to find out it's right my own way."

Will success change Barbra Streisand?

She thought about this a minute. Then she said: "I am now a mature, successful woman. Hah! So I should move out of my tiny third- floor walk-up. And I did, into a large duplex, because the more successful you get, the less secure you get. It's the nature of the business. And I guess I don't have to be so wildly 'different' any more. Even if I'm myself, I'm different enough, so I don't have to play at it."

SHOW BUSINESS experts, awed at Barbra's rocketing rise to stardom, have tried to explain it. Generally they fall back on clichés. As one reviewer wrote recently: "Miss Streisand's talents are akin to the mystical. Since magic, by its nature, cannot be defined, neither can the magic Miss Streisand creates be explained in words. She can be shy, raucous, sensitive, mischievous, womanly, girlish."

But Barbra Streisand has a simpler—and probably much truer—explanation.

"People are drawn to me," she says, "because they don't understand what I'm doing."

End.

[ top of page ]