Look Magazine

December 16, 1969

BARBRA STREISAND : On a clear day you can see Dolly

In a defiant red wig, and horizontal ("the way every woman should be"), Barbra brings a new young sexy dimension to Hello, Dolly! For pointers, she looked at old movies of young Mae West.

BROOKLYN'S BARBRA STREISAND, after winning half an Academy Award for Funny Girl, follows through with two more, expensive Hollywood musicals (totaling $30,000,000) made cheek-to-cheek: Hello, Dolly! and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. The "I'm the greatest star" phenomenon of the 1960's says of her plucking the most envied movie plum in some time: "I did feel that Dolly was a story of older people and that they should hire Elizabeth Taylor to play her. I thought that would be a great role for her first musical. But when everybody seemed to be against me as Dolly [except producer Ernest Lehman and 20th Century-Fox], I took up the challenge. I've never been an underdog in Hollywood, and people get spiteful about about me. They tell lies that make good journalistic copy. I have very little in common with a character like Dolly, who fixes people up and lives other people's lives. I do share the fun she gets in bargaining and buys, and can understand her experience as a woman who has loved and lost. A woman can be any age for that. But I really didn't respond to the Broadway show—a piece of fluff. It's not the kind of thing I'm interested in. I'm interested in real life, real people, and in playing Medea. Dolly takes place in an age before people realized they hated their mothers—the whole Freudian thing. So it wasn't something I could delve psychologically into too deeply, but I could have fun with Dolly and get days off because I didn't have to be in every single scene for once. I call Hello, Dolly! my last big voice picture."

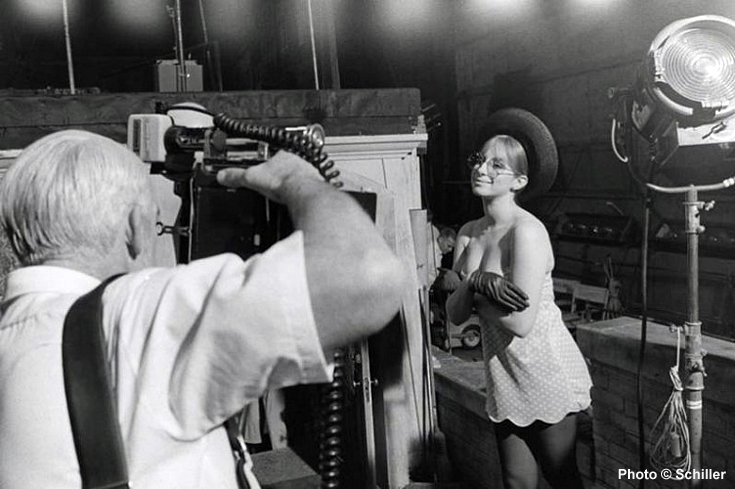

...she tries the schoolgirl look, in a slip. She called Clear Day her "bust picture," and wanted see-through dresses.

ENROLLED IN acting school at 15, Barbra tossed off scenes from Shakespeare and Lorca, never knew she could be a singer, and dreamed of playing Juliet, Medea, Hedda Gabler, "all of which I have time to do yet." She thinks On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, a kind of play with music, gives her the juiciest acting chance so far, the first time she's seen as a contemporary girl. She plays a double part: student, wearing Arnold Scaasi dresses, who undergoes hypnosis to give up smoking and winds up, in Cecil Beaton gowns, an English lady of the Regency period. All top-movie-star treatment, including picking her director, Vincente Minnelli, because she loved his Gigi in 1958. Doing things their way while winning her way, Barbra says, "I like the challenge of working under battle conditions." She has more chutzpa than any star since the 1930's, and usually gets to work any time after ten. "I'm very thrilled like when I'm on time. Something always holds me up," she says. "The two parts in Clear Day come close to my schizophrenic personality," she says, "the frightened girl as compared to the strong woman in me. It was just heaven." All her life, Barbra bolted ahead of her generation. She got famous and rich early, she married young, she even gave up smoking at 12, after sneaking Pall Malls on her Brooklyn roof for two years. Unlike the Clear Day girl, she would never permit hypnosis: "I fight losing control in any way. I would never touch drugs. I hate the taste of wine and liquor, just hate it."

Barbra, in warm furs, tries out a glacial mood.

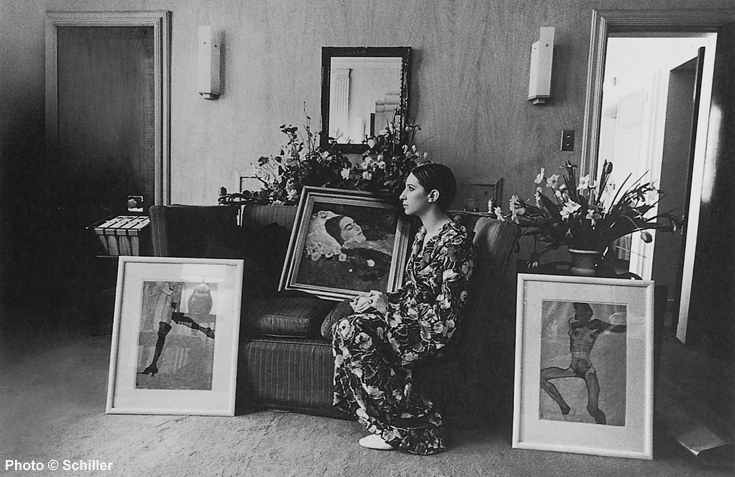

RUMMAGING THROUGH thrift and antique shops for finely made old dresses (which she wears), furniture and paintings has a grip on Barbra. "I'm a slave to all my tchotchkes," she says, as they pile up in her Beverly Hills house. New York duplex and the Manhattan Storage Company. She is now settling down happily again in "my hometown city of New York, where I feel much safer after the Sharon Tate murders in Hollywood." Her next film, The Owl and the Pussycat, will be made in New York. "It's such a shlep doing those big musicals—it takes a year, a whole lifetime away from you, rehearsing, pre-recording, fittings, etc. Now I can make a little movie in ten weeks, no songs, like a normal person. I mean, you do a movie and you go home." But how about the rumor she may do the big life of Sarah Bernhardt? "Yeah, I think it's inevitable that I'll play Sarah, but there's nothing in the works yet. I can wear my hair in the frizziest look, and you know Bernhardt acted Hamlet, not Ophelia, and so will I. It's little things like these that influence me to do a part." She's finding time for sports, learning to swim and play tennis, "to use my body and find out what nature's all about. I'm not used to physical exertion. I think children who grew up in these Jewish homes where the mother always thought if you swam, you drown, or if you take dancing lessons, you break all your bones, are handicapped. I don't want my son Jason to see fear in Mama's eyes when she's out there on the diving board and he says, 'Jump!' What's he hinting ? "

At 9 a.m., at Claridge's in London (part of Clear Day was shot in England), she writes a check for three new pictures, a Gustav Klimt painting and two watercolors by Egon Schiele.

BARBRA'S "strong woman" side comes off more visibly in Hollywood than her covered-up "frightened girl" side. Blunt, basic, honest, overpowering, "this young newcomer" who gets the big parts awes the old movie professionals. She's already catching up with them in movie-making know-how: production, financing, directing, cinematography, lighting, wardrobe, distribution, publicity. Dolly's director, Gene Kelly, says, "She learns and remembers. ... I found her attack exciting." Most of all, she is an authority on how a real movie star can get ahead. She didn't watch thousands of Hollywood fantasies in dark Brooklyn movie houses when she was a lonely child, and learn nothing. She still lives the dream of "being the girl who gets Rhett Butler."

She takes a hard look at every movie set to make sure that it is designed for the left side of her face — it highlights the crook in her nose beautifully. "She has youth, but she's a difficult girl to photograph," says Harry Stradling, cinematographer for her first three movies, and a Hollywood veteran of 50 years. "She knows what's good for her, and 99 percent of her ideas are right. Even on her first movie, Funny Girl, she said to the director, 'How about doing it this way?'" For her close-ups (she complained to director Gene Kelly she didn't get enough in Hello, Dolly!), the movie camera is fitted with a sliding diffusion glass in front of the lens, an old trick for older stars, so that no unglamorous lines of living will appear, though the Streisand face is only 27 years old. Barbra is so smart in doing her own makeup that she designed a portable makeup table with lights that can be adjusted to match the exact lighting of her movie set at any moment.

As with most stars, Barbra has the right to approve all photographs of herself, but on Clear Day, she ran up a historic retouching bill, $25,000. Afterwards, she "killed" most of the retouched photographs. "She looks at herself pretty rough and emphasizes her good points—her eyes, her nose, her hands and her beautiful skin," says Clear Day producer Howard Koch. "And she's the homeliest gorgeous lady I've ever met." When viewing color slides of herself projected on the screen, Barbra, in total concentration, squats on the floor eating Indian nuts. She places her still photos in three categories: OK, Hold for Second Look, and Kill. She utters "Kill" so often that someone asked her if she wears a hawk on her wrist. Barbra's "Kill" system is faulty, though, because it's impossible for her to remember which of the hundreds of photos of herself she's killed when they are all primarily shot from the same angle. She still doesn't know that Marilyn Monroe worked out a foolproof system—she shredded with pinking shears the photos she hated.

"I haven't made a mistake with my public yet," Barbra claims, with her deeply thought-out sense of what's right for her career. Everybody agrees, but people who have worked with her giveth and taketh away when discussing her methods. For example, British designer-photographer Cecil Beaton, accustomed to the ways of the royalty of palaces and studios, thinks that "Barbra will be producing and directing soon. In designing gowns for her, you never have to be afraid to ask her, 'Is this going too far?' So many actresses are afraid, they don't dare, but with her you can go whole hog. But she'll never accept anything until she's convinced in her own mind that it's 100 percent right for her. She'll never just say, 'Oh, I suppose that's all right, let's go out to dinner.' It's a constant battle of attrition with her and her taste—which is very exhausting."

Now, to stir up skepticism, Barbra may contradict everything she's done before to make herself gorgeous and the biggest star. In The Owl and the Pussycat, she may show all the angles—even her right side—as she saw uninhibited Elizabeth Taylor do in Virginia Woolf. "The three big movies I've done so far are real movies, just the kind I wanted to do as a kid. You know, the hair's in place, pretty clothes, everything glamorous. But now, for the first time, I'm doing without wigs, hairpieces, dyes. It's just going to be me, that's all it is, the me that's natural and very today. I want to be a part of my own generation; up to now, I've always felt out of it, older somehow. I don't want to care as much as I did. I don't even particularly want to look good. Maybe there are more bad angles to me than good. I just want to be human. It's a different kind of mental attitude I'd like to see from myself at this point."

"I don't believe Barbra means this," says Harry Stradling. "No woman wants to look bad." ("By the time this is in print," she herself says, "all my opinions may change. One day I say I hate diamonds and love rubies; next day, I love diamonds.")

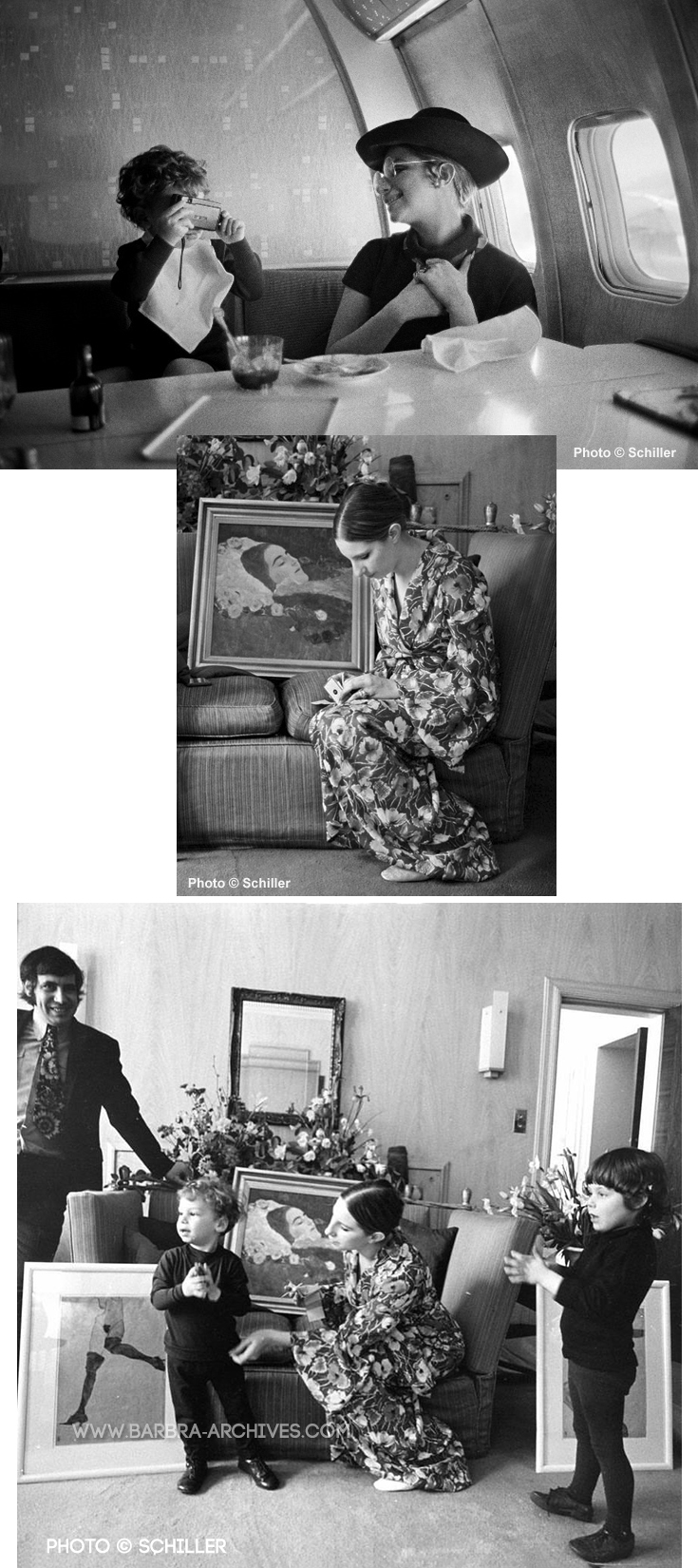

(Top photo): On flight to London with Jason, she hides behind Madison Avenue glasses.

Barbra is proud of being a good mother. "I wouldn't like to live in Hollywood all the time," she says. "I don't want to send my son to school there— that's the main reason. I want him to go to school where there are children from all types of financial and integrated color backgrounds. I want him to play on the streets. I want to get a house where he can sit out on the sidewalk like I used to do. And I can never understand the mentality of these people in Hollywood who ask me, 'Do you have your baby with you?' Where else would he be?"

Jason, 3 in December, already goes to school two hours a day. His father, Elliott Gould, is now likely to become important in movies after his outsized, scruffy, Teddy bear performance in Bob & Card & Ted & Alice. Barbra thinks that her estranged husband "is the American equivalent of Jean-Paul Belmondo. Hell be a big star. I think he's the representative of the 30-year-old man, the postgraduate, which is a terrific symbol of our times." No comment as to if they will get together again, or act together in a movie, except,"We're not dead yet."

END.

Related Pages:

Schiller Photo Outtakes

[ top of page ]