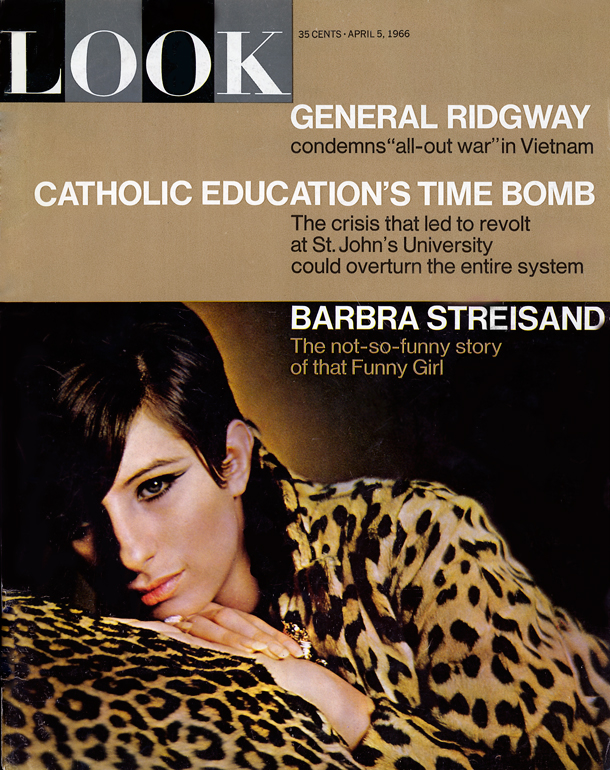

Look Magazine

April 5, 1966

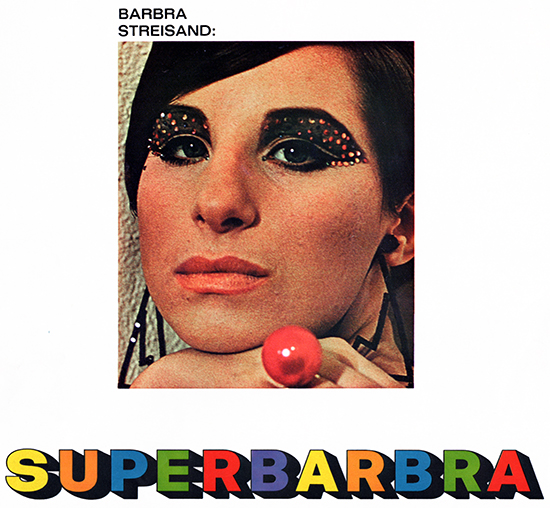

SuperBarbra

by Thomas B. Morgan

Photographed by Howell Conant

IN NEW YORK, not long ago, Barbra Streisand, 23, hung up her laurel after 21 months on Broadway in Funny Girl. But she was not resting. She was bound to pack in two quick weeks of rehearsal, recording and taping sessions for Color Me Barbra, her second one-woman TV show. It is scheduled for CBS-TV, March 30.

I say packed in because, at the end of that sprint, she was booked to show at the fall fashion previews in Paris. Barbra Streisand? The early Streisand played kook, brashly clad in torn hose, thrift-shop gowns and ratty furs. Her appeal caught up the rebel instincts of rock-fed, disk-buying teen-agers. The later Streisand—married, starred, contracted and sponsored—has broadened her appeal, cultivating the taste for high fashion and affluence of upward-yearning young adults in the big mass audience. Recently, her name turned up on a puff list of the best-dressed women in the world. "Maybe now people will stop calling me a kook," the columns said she said. And, inevitably, her visit to the Paris salons would add a little glitter to her billing in the comedy of haute couture. The clock, then, was the thing during those two tense weeks of Color Me Barbra. One went along to see Barbra run.

Photo : Barbra shares televised moment with Eakins's The Concert Singer, Philadelphia Museum.

I was not one of Barbra's instinctive fans. Going on 40, I could not adjust her to my private dream of favorite singers. Past and present, their voices always struck a blue note, verified by lives lived long and deep. Ella, Judy, Edith, Bessie, Anita, Mahalia and Billie paid their dues with wounds, tasted defeat, were eclipsed, fought back and won, at least temporarily. Illness, broken romances and even the failure of success made them, above all, believable. Then along came Barbra, clearly in the great tradition vocally, but not of it. Her story was antiromantic. She grew up in Brooklyn among nice middle-class people. She was a normally unhappy child. And her swift ascent from clubs to theater to records to TV (and next year to Hollywood) deprived her, despite a Sherlock Holmes nose, of an essential credential: pain. There was no irony, no mystery about her. She seemed only surface. And if her voice did carry that vital note, then only one theory explained it. The sound must be contrived, artificial, an act.

The first time I saw her close up, Barbra was arriving late for rehearsals at a dank hall in the east Seventies. She wore a floppy hat, fur cape, aquamarine slacks and matching suede shoes with a strip of maroon across the instep. She was not pretty, but one did not expect anything else. It is not, however, the nose. The nose is beautiful. When she started out, prospective promoters suggested she trim it. She had better sense, and the nose remains, aesthetically and commercially right. Rather, it is her eyes, set too close together and somehow chilly. Her mood was phlegmatic. We shook hands, and she went to work, going through her paces with choreographer Joe Layton around chairs and over benches while director Dwight Hemion followed, peering at her through his fingers, which represented a camera. She was professional, methodical, precise. There was no nonsense. She was a star who combined song with dance and comedy as skillfully as any woman her age in the world. She did not need magic.

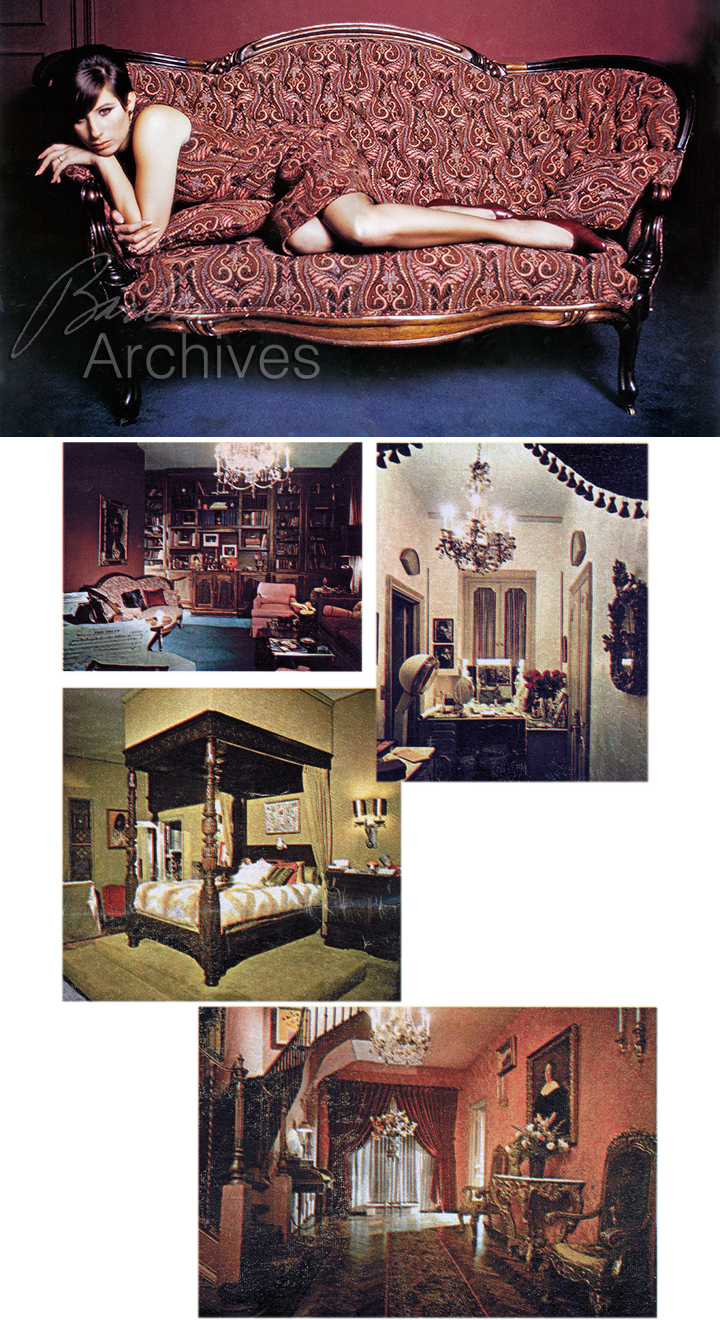

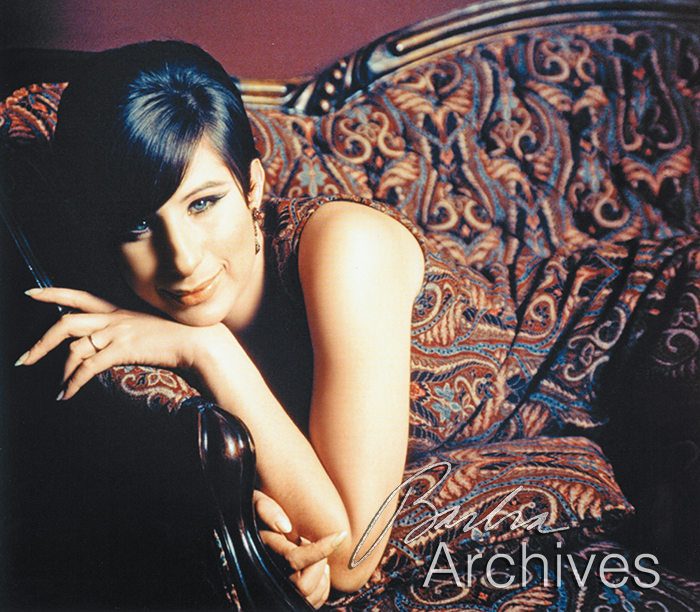

(Photos, above): Gingerbread house. Barbra and Elliott Gould live like Gretel and Hansel in a Manhattan penthouse, once the home of Lorenz Hart. Barbra ordered dress to match paisley love seat in their richly appointed den. Dressing room displays one of their five antique chandeliers.

Then, midafternoon, like a premonition, Sadie arrived fresh from the barbershop. Sadie is a shaggy, miniature white poodle. Barbra scooped the dog into her arms, kissed her and carried her over her shoulder as she walked through the next phase of the rehearsal.

Later, a hapless-looking delivery boy stuck his head in at the door. Barbra disappeared, then returned in a moment with a glittering brooch in a velvet case. She pinned it to her sweater.

"How do you like my new brooch?" she asked. "I'm crazy about brooches. I pass these things in store windows and I say, 'Go call that guy!' "

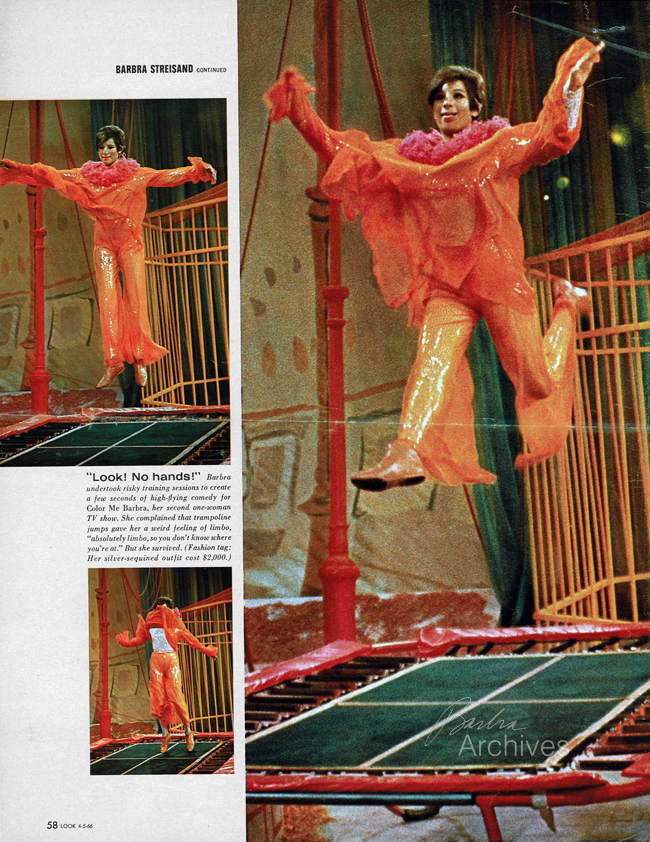

She did not say who took the orders. Finally, toward evening, she climbed up on a trampoline and began practicing leaps and flips, assisted by an instructor and anxiously watched by Hemion and Layton, both quiet men in sneakers, and her manager, Martin Erlichman, who wears suede shoes. Sadie whined.

"He's worried," Barbra said in midair.

"Who isn't?" Hemion replied.

"That's a five-million-dollar risk," said another.

"Fifty," Erlichman said.

Barbra tried another flip, flopped, and climbed down to catch her breath. She drooped.

"What I won't do for the television audience," she said.

"It's not for them, it's for you," Layton noted.

The instructor's assistant, a muscular girl, took over the trampoline to demonstrate an intricate leap. Promptly, she lost her balance and fell through the springs. She was uninjured, but the spectators were shaken. Then Barbra tried again.

With an assist from the instructor, she negotiated a flip for the first time. She stuck her tongue out at Layton. Barbra tried again and again, sprawling awkwardly, crashing to the canvas, and almost bouncing out of control. Sadie cried. The brooch gleamed. And, most of all, the face, the flying arms and the lumpy figure suggested a will to do what was clearly impossible with inadequate means. It was then that I began to believe a little.

Over the next six days, Barbra rehearsed and studied daily with Hemion and Layton and, most evenings, with musical director Peter Matz, a bushy-haired man who has known her since the first Streisand record album. He told me he has had some difficulty working with lesser singers "because my ears and head are full" of Streisand.

There were also claims on Barbra's time presented by her agent, business manager, accountant, lawyer, dress designer, hairdresser, press agent, network executives, sponsor and sponsor's advertising representative. She also went on for interviewers and photographers from CBS, a photo agency, three newspapers and two magazines. Some of the load was shared by Erlichman and her husband, actor Elliott Gould, who are two of the three principals in Ellbar Productions. Ellbar's business is show business, starring Barbra Streisand, principal number three. "The main thing," Erlichman said, "is to guard her against too much public exposure as a performer. She demands a lot from an audience. And people can take only so much of it at a time."

(Photos, left): Look! No hands! Barbra undertook risky training sessions to create a few seconds of high-flying comedy for Color Me Barbra, her second one-woman TV show. She complained that trampoline jumps gave her a weird feeling of limbo, "absolutely limbo, so you don't know where you're at." But she survived. (Fashion tag: Her silver-sequined outfit cost $2,000.)

Barbra ran. She was still on her Funny Girl schedule and never called it a day until well past midnight. She got her sleep by barring appointments before noon. She ate, nibbled, noshed on the fly. She did not laugh much. She asked for things politely, but never said thank you. And when she had nothing else to do, she penciled sketches of her face, planning rhinestone eye makeup for Color Me Barbra.

Once, a photographer asked her to take time for a visit to Pulaski Street, Newkirk Avenue and the other Brooklyn streets where she had lived when there were three "a's" in her first name. He said that one might make a case for Brooklyn as the "Hometown of Barbra Streisand." The borough needed something, now that Ebbets Field had been torn down, Marianne Moore driven out, Coney Island deserted and the Mafia moved to the suburbs. But there was no music in Brooklyn for Barbra. "I feel Brooklyn is all in the past. I live in Manhattan. My mother lives in Manhattan. There's nothing for me in Brooklyn."

Yet it was not until she talked about Brooklyn that my inclination to believe was stirred again. It started when she lit a cigarette and recalled smoking at age ten in the bathroom at home in Brooklyn. That was 1952, which reminded me that she was a member of America's first TV generation. "When I was four," she said, "I used to visit the apartment of my friend Irving . . . whose parents had a TVs-inch television set. I remember his mother cooking stuffed cabbage and knitting every afternoon, while we watched Laurel and Hardy through a magnifying window." Barbra told me that she was the smart aleck of her class at Brooklyn's Yeshiva, the Hebrew school she had attended until third grade. "When the rabbi would go out of the room, I'd yell, 'Christmas! Christmas!'—a bad word for a Hebrew school. But even I couldn't bring myself to cross my fingers."

From age seven on, she said, she grew up yearning to be a movie star, a ballerina, an actress. She could think of only two high-school chums, both "pretty" girls. Her father had died when she was 15 months old. Her mother had wanted her to be something normal, like a secretary, but Barbra refused, and let her nails grow to ward off typing lessons. Her passion had been mirror-watching, spending hours trying on dark lip- stick and eyeshadow bought with her school-lunch money. "Somehow," she said, "it made me think I was attractive."

She said she could not wait to get out of Brooklyn and envied her older brother, who went to college "and escaped." At 14, she had worked in summer stock in upstate New York; at 15, hung around evenings at an off-Broadway theater; at 16, moved to Manhattan to study acting. Just like that. There was pathos in Barbra after all, not so much in her past as in her bitter rejection of it in the present. She won the inevitable talent contest at 18, a singing date at a Greenwich Village nightclub, guest appearances on TV, a part in a musical, a record contract, nightclub and stadium dates, and on to stardom. There were instants of terror and doubt. On the first day of rehearsal for her first role in an off-Broadway play, she vomited. In the midst of a tryout at Actors Studio, she wept. Rehearsing for the talent contest, she sang for friends, but insisted they turn their backs. In San Francisco, after her career had begun to roll, she developed a singing block. During the run of her first musical, she was late to work 36 times. And as Funny Girl wore on, she became increasingly uncertain. "I was scared. Performing made me nervous, sick. I was scared I wouldn't connect. Really, I prefer TV or movies to the theater. I'm afraid of audiences now." (But she opens Funny Girl this month in London.)

(Photo, right): Mr. Gould massages Mrs. Gould's weary neck during 32-hour TV marathon. Coproducer Layton is tired third party.

What rendered all of it touching was Funny Girl's not-so-funny summation. "I always knew I would be famous," she said. "I knew it, I wanted it. I always wanted to be out of what I was in. Out of Brooklyn. I had to get out. I was never contented. I was always trying to be something I wasn't. I wanted to prove to the world that they shouldn't make fun of me. The girls sometimes made fun of me. When I got to Manhattan, where people really live, I couldn't train myself to keep one hand in my lap. Now, I love formal dining and place cards. But it doesn't make me feel comfortable. I'm not comfortable sitting down to a formal dinner. I'm more comfortable standing up and eating out of three pots on a stove. I love Cokes, and cones and French fries that taste of bacon, like you get in greasy spoons. I love greasy spoons. My mother and I, we never went out to eat. She didn't pay much attention to me. I hired my first agent because he took me out for dinner. A few years ago, I could be bought for an avocado. Recently, after a late party, I was all dressed in diamonds and furs, and I had this urge for rice pudding without raisins. Some people like it with raisins. I like it without raisins. Well, I had this urge, and every place was closed, but Elliott found a waterfront diner that was open.... We could have gone to the Automat, I suppose. I like the Automat. You put in the nickels and get what you want—pies, cakes, sandwiches. But you know, nowadays, it's hard for me to go to the Automat. I mean, people know me and inhibit my eating."

The second week's work on Color Me Barbra had been minutely planned. There would be no real opportunity for experiment or even a fiddle with the formula that had worked for My Name is Barbra. As before, a location scene came first. The directors of the Philadelphia Museum of Art had allowed Ellbar Productions 16 hours for night shooting on the premises. The second and third scenes would be filmed at a CBS studio in Manhattan. One simulated a circus and required live animals. The other, again as before, set a bare stage for a concert in front of a live audience. Except for the live segment, Barbra would prerecord most of her music. The recorded music then would play during the filming of dance and comedy routines with synchronized lip movements. If the desired effect was achieved, the contrast between lyrics, tempo and the scenes themselves would create a new appeal not inherent in any of the separate elements. It had been one of her most effective tactics ever since she sang Happy Days Are Here Again as though those days had just gone. She would croon "I love your eyes, your cheeks, your hair...." to a hairy animal and belt out "gotta find someplace ... some brand new place" in a gallery of Picassos, Mirós and Villons. The show, no doubt, would go on. But to make it go somewhere required Barbra as Superbarbra, the energy girl, the couture kid, the flack's darling, Queen Midas —who also sings well. It was the point I had been missing all along.

On the first day, Barbra rehearsed five more hours with Hemion and Layton. Then, at 7 p.m., she began an eight-hour recording siege with Matz and a 33-piece band. When it was over, she helped select the best takes for use next day in Philadelphia. A friend warned Barbra against fatigue hoarseness. "Hoarse?" Barbra growled and waved her hands. "Hoarse! I don't get hoarse. What hoarse?"

That weekend, in Philadelphia, Barbra worked almost 32 hours straight. She began Saturday at noon: try on costumes, submit to hairdresser, apply rhinestones to upper eyelids. At 6 p.m., she stepped before the camera. The shooting went on all night and, by a new dispensation of the Museum, all day Sunday until 8 p.m. Cameras broke down, lights blew, cables snapped, and technicians slept on their feet. But nothing fazed Barbra's remorseless preoccupation with self. Whatever Joe Layton's pop fantasy might mean to TV, it meant Barbra to her. She slaved, she fueled. Hour by hour, she ate pretzels, potato chips, peppermint sour balls, a hero sandwich, pickles, stuffed derma, a corned-beef sandwich, coffee ice cream, roast beef on rye, Swiss cheese on white, hamburger, Danish and petits fours. She drank: coffee, orange juice, ginger ale, cream soda. Husband Elliott rubbed her back and held her hand. Barbra complained only once: Her feet hurt.

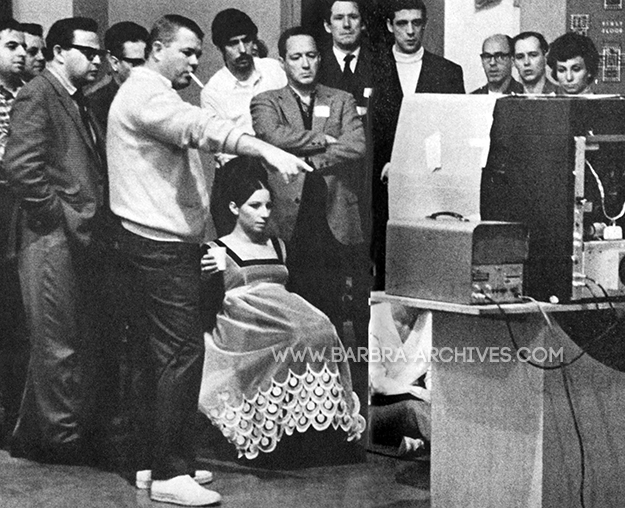

Photo below: Scanning playback on monitor, Barbra listens to advice from coproducer Dwight Hemion. But she is the one who dominates production of her show. [Note: Marty Erlichman and Hemion are left of Barbra. You can also see Joe Layton in white turtleneck.]

The next night, after a daylong sleep, Barbra recorded songs for the circus scene. The following afternoon, she leaped into the actual sequence. Dressed in a $2,000 silver-sequined outfit and orange-leather boots, she played ringmaster to a pony, elephant, leopard, llama, tiger, anteater, baboon and a squad of penguins and pigs. She swung on a trapeze, bounced on the trampoline and tap-danced through sawdust. There were no mechanical delays, but the penguins waddled off, the elephant balked, the pony fell, and six times, the tiger tore out of his cage. Shooting time: 24 hours, no sleep. "It was wishful thinking to think we could do these things in a night," Barbra said, without rue. She was working for Barbra, spending herself. Even with overtime for the crew, she saved money. A leisurely schedule would have cost Ellbar more. Besides, in Paris, the salons were waiting. "No complaints," Barbra said. Another big sleep, then Barbra's concert. On the seventh day, new props and 281 bleacher seats were moved into the studio. The dress-rehearsal audience filed in at 6. Most had been recruited from Barbra fan clubs. "We know they'll applaud," one of her agents said. The fans were young and fanatic. Barbra sang; They left, and more fans filed in. As Barbra sang again, I found myself wondering whether she might have given out more before less dependable people. The manufactured audience is finally the bane of all popular singers. One must capture a passing mood, exploit it, move on. The already captivated cannot tell you when to move, the way to go. I was beginning to worry about Barbra. I was on the verge of surrendering.

Afterward, as Barbra went off to the control booth to review her work, I walked around to her dressing room. Her mother was there. She is a round-faced, round woman who wears her hair piled youthfully-high on her head. I remarked on the songs Barbra had chosen for the TV show, especially a funny arrangement of One Kiss. Mrs. Streisand told me that she, too, had made a record of One Kiss. "Of course," she said, "we sing it our own way." And then she sang me a few bars of her version, in a very nice contralto.

I saw Barbra for the last time a few hours before her flight to Paris. She had invited me to a quick tour of her penthouse on Central Park West, so I brought along a tape recorder for walk-talk, snatched from the hands of my eight-year-old son.

The apartment is on the 21st floor, with a view across the park toward the East Side peaks, but not to Brooklyn. The Goulds live on two floors. Deep-red patent leather adorns the kitchen walls. A collection of antique hats and shoes is stored in a sewing room. The most extravagant of five chandeliers (one hangs in the upstairs bathroom) drips from the dining-room ceiling. A glorious Aubusson rug dominates the living room. Barbra had the room painted three times to suit its pale tones. Red-damask wallpaper and an 18th-century French desk tone up the foyer. Trophies and mementoes cover two sides of a narrow hall to the den: seven gold-record albums (each honoring the sale of copies worth more than $1,000,000); a letter of thanks from the President for her appearance at last year's Inaugural Ball; award certificates from various academies and committees; and a laminated chart from Billboard magazine, commemorating the 1964 week when five Streisand albums were listed among the 100 best-selling albums in the country, including People, in first place. A Steinway piano crowds the den, but here, Barbra is proudest of her drapery linings—herringbone under red velvet—and the paisley fabric on the love seat. "I have the same herringbone lining in one of my fur coats," she says, "and a dress to match my sofa." Finally, upstairs, a Jacobean double bed rests thronelike two-steps up from the bedroom floor, against walls covered with green brocade. On a bedside table, a gilt-edged photo of Barbra eating a Lolita lollipop is inscribed: "Too Eleot i wuv you Barbrra." My defenses crumbled.

The apartment is on the 21st floor, with a view across the park toward the East Side peaks, but not to Brooklyn. The Goulds live on two floors. Deep-red patent leather adorns the kitchen walls. A collection of antique hats and shoes is stored in a sewing room. The most extravagant of five chandeliers (one hangs in the upstairs bathroom) drips from the dining-room ceiling. A glorious Aubusson rug dominates the living room. Barbra had the room painted three times to suit its pale tones. Red-damask wallpaper and an 18th-century French desk tone up the foyer. Trophies and mementoes cover two sides of a narrow hall to the den: seven gold-record albums (each honoring the sale of copies worth more than $1,000,000); a letter of thanks from the President for her appearance at last year's Inaugural Ball; award certificates from various academies and committees; and a laminated chart from Billboard magazine, commemorating the 1964 week when five Streisand albums were listed among the 100 best-selling albums in the country, including People, in first place. A Steinway piano crowds the den, but here, Barbra is proudest of her drapery linings—herringbone under red velvet—and the paisley fabric on the love seat. "I have the same herringbone lining in one of my fur coats," she says, "and a dress to match my sofa." Finally, upstairs, a Jacobean double bed rests thronelike two-steps up from the bedroom floor, against walls covered with green brocade. On a bedside table, a gilt-edged photo of Barbra eating a Lolita lollipop is inscribed: "Too Eleot i wuv you Barbrra." My defenses crumbled.

(Photo, left): Barbra, in tea-sipping scene, suggests actual eat-and-run conditions of work on Philadelphia location. She is no food fadist, loves Chinese chow, chocolate mousse, coffee ice cream and Coney Island hot dogs.

Later, we talked while Barbra and press agent looked over color slides of publicity photographs. She used a professional's magnifying flashlight and dictated markings for each picture according to its merits as a reflection of herself. My tape recorder hummed. "Somebody else could do this," Barbra said, dropping another slide on her pile of rejects, "if only I didn't care so much."

I remember that our conversation lasted 30 minutes and that she said, "I was never kooky, so I haven't changed. What I've always had is a sense of the right thing for me." The rest is lost forever. When I returned home, I found my recording tape snarled in the mechanism. I straightened it out and played it back, but there was no Barbra. Instead, my son's urgent voice: "Hello, Batman. Hello, Batman. This is Robin. ZLONK!" I should have been angry (at him? at myself?), but I was not. I understood, I believed. Cry me a river, Barbra!

END

Related: Color Me Barbra TV Show

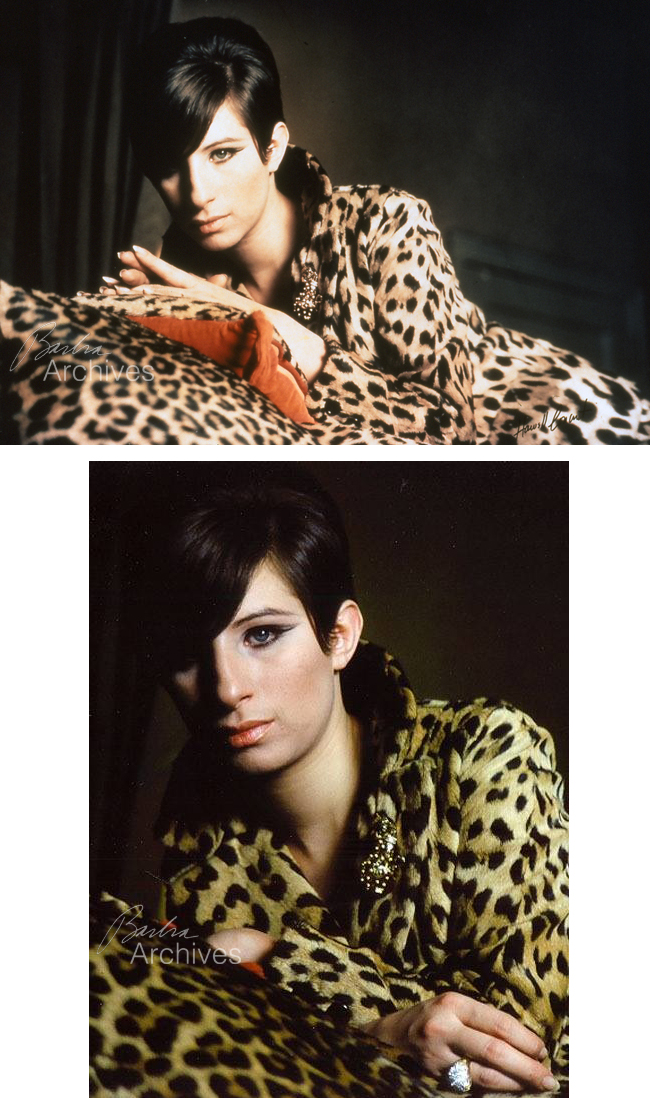

Photo Outtakes

(Above) Three Piece Custom Leopard Skin Suit, Circa 1966 Mid 1960s suit, consisting of a leopard skin hat, jacket and short skirt. Including a form fitting skirt ending at top of knee, fully lined and buttons and zips on each side.

Photographer Howell Conant captured iconic images of Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly. He photographed Streisand a few times, for Life and Look magazines.

[ top of page ]