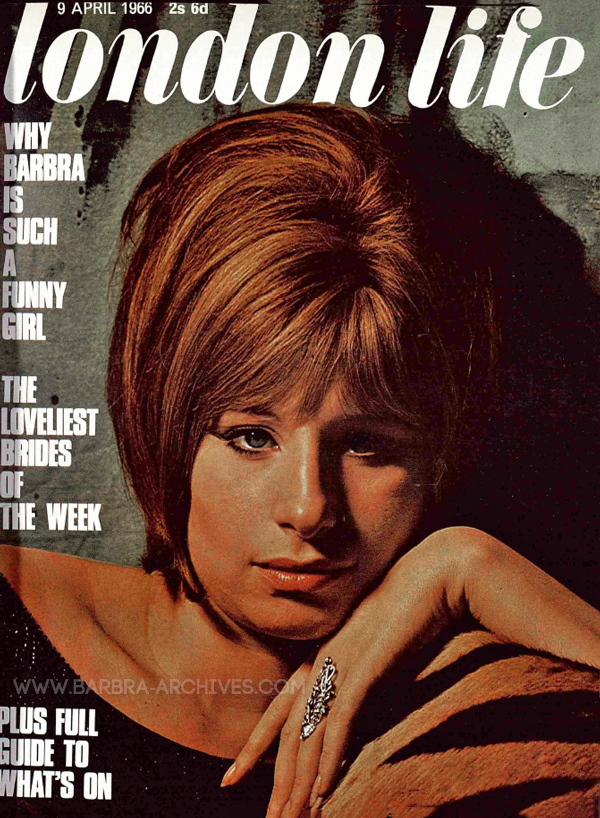

London Life

April 9, 1966

American musicals create a sense of excitement usually quite out of proportion to their actual value on the market. Each fresh import is heralded with an even greater fanfare than its predecessor. Funny Girl is the most potent example since My Fair Lady. The theatre was deluged with an unmanageable flood of advance bookings and one customer wrote a polite letter quietly inquiring how it was that the first night had been sold out before either the theatre or the opening date had been announced. This is because keen applicants apply direct to the impresario as soon as it is known that the show is definitely coming.

The reason for this general tizz most probably springs from deficiencies in the home-grown product. British musicals are perhaps artistically more pleasing than American ones — the story coherent, the music intelligent, the direction well integrated. But they lack, firstly, good standard songs, and even Lionel Bart has only achieved this once. Secondly, the conditions under which a British female musical star could develop are absent; and, lastly, native reticence prohibits that over-blown, theatrical vulgarity which audiences frankly adore. The climate does not encourage a visual number like Hello Dolly or stimulate the big, simple emotional outbursts like So in Love.

Funny Girl contains these three elements—each at a maximum state of development. In fact, it is a safe prophecy that a number of London's theatre critics are going to find the whole thing just too much. The show, which opened in New York in March, 1964, is based on the early life of Flo Ziegfeld’s comedienne, Fanny Brice, taking it up to her final break with Nick Arnstein. In 1925, Vanity Fair—the most swinging American magazine of the inter-war years — nominated Fanny Brice for its hall of fame: “Because, from the humblest beginnings on the East Side of New York, she came to be acclaimed as the best comedian on the musical-comedy stage: because she made the trial of Nicky Arnstein, her husband, one of the most diverting on record; because she is a financial genius of high rank; and finally because her mastery of pathos, mingled with her extraordinary sense of the comic, has brought her to stardom for Belasco.”

Quite a lot to live up, both for the composer of the show and for the girl playing the title role. The book for the musical was written by Isobel Lennart and the show was put on in America by Ray Stark, who is married to Fanny Brice's daughter, Frances. Its antecedents are therefore impeccable. The script also lends itself well to the special talents of its composer, Jule Styne, who has explored similar territory before, in Gypsy; backstage tears and chuckles, interpolated with affectionate pastiches of theatrical forms that now have a patina of nostalgia. In Gypsy it was vaudeville: its travelling troupes and comedians and later its strippers ("If you want to bump it, bump it with a trumpet"). In Funny Girl it is the Ziegfeld Follies with the glitter, grand staircases and general campery of its big production numbers that Styne recreates.

Jule (say it "Julie") Styne is, surprisingly, the son of a Russian-born Bethnal Green egg inspector. But he went to America when he was eight: “When I came back in 1956," he relates.

"I went to look at our old house— 11 Ducal Street. They were tearing it down. But I managed to salvage the nameplate and the knocker to take home with me." They now sit in his luxury apartment along Park Avenue. He started song-writing when he was 35, and in the subsequent 25 years he has achieved more than 1,500 songs. Mention a few and people say: "Oh, did he write that?"

"I went to look at our old house— 11 Ducal Street. They were tearing it down. But I managed to salvage the nameplate and the knocker to take home with me." They now sit in his luxury apartment along Park Avenue. He started song-writing when he was 35, and in the subsequent 25 years he has achieved more than 1,500 songs. Mention a few and people say: "Oh, did he write that?"

Among them are Five Minutes More, Three Coins in the Fountain, It's Magic, Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend, I'll Walk Alone, Just in Time and The Party's Over. Styne is quick to point out that he has custom-built vehicles for his stars. Among them are Doris Day, Ethel Merman, Carol Channing, Nanette Fabray, Carol Burnett, Geraldine Page and the late Judy Holliday. He is a master of creating a soliloquy with which his leading lady can close the show—Judy Holliday's I'm Going Back, in Bells Are Ringing, Ethel Merman’s bitter outburst at the end of Gypsy. Funny Girl has one, too, a classic example of the guts-conquering-set-backs school called Don't Rain on My Parade, which is technically difficult to sing— at least one Famous Lady of the American Musical totally failed to bring it off at the London Palladium last year.

It is undeniable that Styne’s carefully calculating approach has helped Barbra Streisand to success in Funny Girl. “There is no such thing as the overnight sensation,” Styne points out. “Barbra had seven years of grooming before she became a star. Doris Day and Ethel Merman had to work hard before they became stars." But the right vehicle helps, as Carol Channing — certainly no inexperienced debutante — no doubt discovered when she tackled Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The American musical stage is dominated by its women. (Check list, for a starter: Ethel Merman, Mary Martin, Gwen Verdon, Judy Garland, Carol Channing, Carol Burnett, Tammy Grimes, Patricia Morison, Judy Holliday, Ginger Rogers, Lena Horne, Pearl Bailey and now, apparently, Lisa Minelli [sic] —Alfred Drake can't have appeared opposite all of them.) This cult of the Broadway brass is probably some sequin-dusted extension of the American male's domination by the female that social commentators are always talking about, but even so the arrival of another is always exciting. These women have a unique magic that no Englishwoman possesses: our two greatest stars — Gertrude Lawrence and Julie Andrews — acquired their finish on the Great White Way. They are glamorous, tough, professional but even the toughest of them all, Merman, can provoke tears when she sings That Old Feeling.

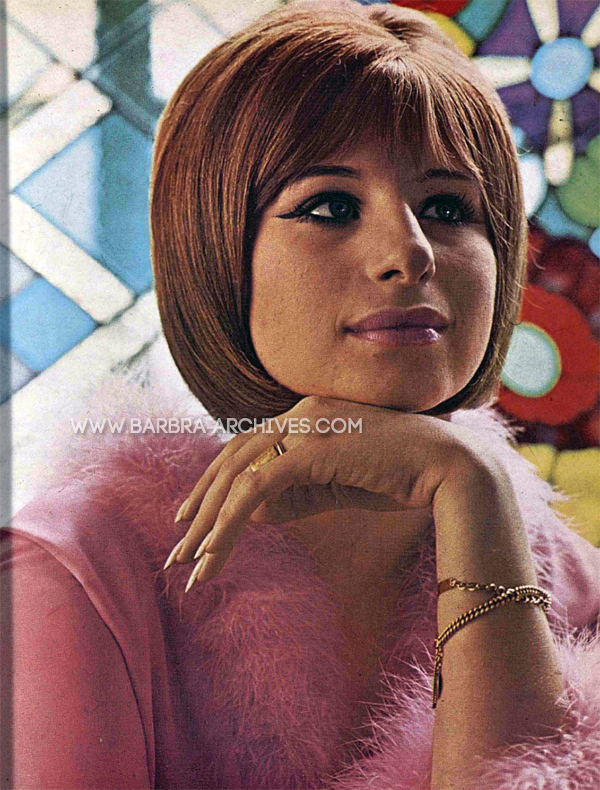

Barbra Streisand’s reputation spread slowly into this country. It was partly through transatlantic show-business chat, partly through a recorded recital simply called The Barbra Streisand Album. Way back in 1963 this was the disc the "smartest" people had lying casually on their Casa Pupo rugs. The LP revealed two things which, added together, almost invariably indicate a star in the offing. One was a voice of great range, both technically and emotionally. The other was a highly individual attack that created as many anti-fans as fans. (Incidentally, the similarity with Maria Callas must not be pushed too far, but there is a rudimentary assonance.)

Her first recordings showed a vocal abandon and musical wit, as well as a tender way with a ballad, that was rare. She sang Happy Days are Here Again with a slow, steady, heavy pulse that completely retrieved a specious song; she played hell with Harold Arlen's Down With Love; she beat a deal of truth out of A Taste of Honey; and even got herself on Children’s Choice with Big Bad Wolf. She was known as a “method singer."

But as album succeeded album, and the sleeve photographs became more bizarre, the songs became more self-involved, more torchy and too frequently pitched for the same effect. The gaiety and gamine wit seemed to be left behind. Early this year she hit the charts with a reversion to the old style Second-hand Rose, a good sign.

Meanwhile gossip mounted: “She wears terrible old fur coats," “she collects junk," "they won't let her make a film until she has her nose straightened." A legend was in creation. She really arrived when commentators actually managed to get both her first and second names correct.

Funny Girl is well devised to make use of Streisand’s various talents. Her instinct for comedy gets full release in the Follies numbers—as when she arrives for a lovely wedding sequence heavily pregnant, or in a First World War number when she is Private Schwartz from Rockaway (“my bagles gave a spin, oi-yoi"). The musical is also shot through with straight ballads; notable among them is People, the popularity of which inspired one of the New Yorker's most likeable inventions: "Penguins who need penguins are the happiest penguins.” But the first song Streisand has to put over in the show is called I'm the Greatest Star, a totally egocentric statement of ambition in which she makes wild claims for her talent, ranging from joke-telling to the playing of Camille: “I'm a natural cougher."

It takes no great effort to imagine a short-list of people to whom, should they sing this song, the only possible answer would be: "Oh no you're not, dear." But Streisand may well get away with it, oven though it is the most formidable number with which to approach a new audience. Being British we may say: “Yes, well, give us a dozen years or so to make up our minds.” But we mustn’t, otherwise Miss Streisand may join the growing ranks of stars who do not appear in London until they are rather past their prime.

End.

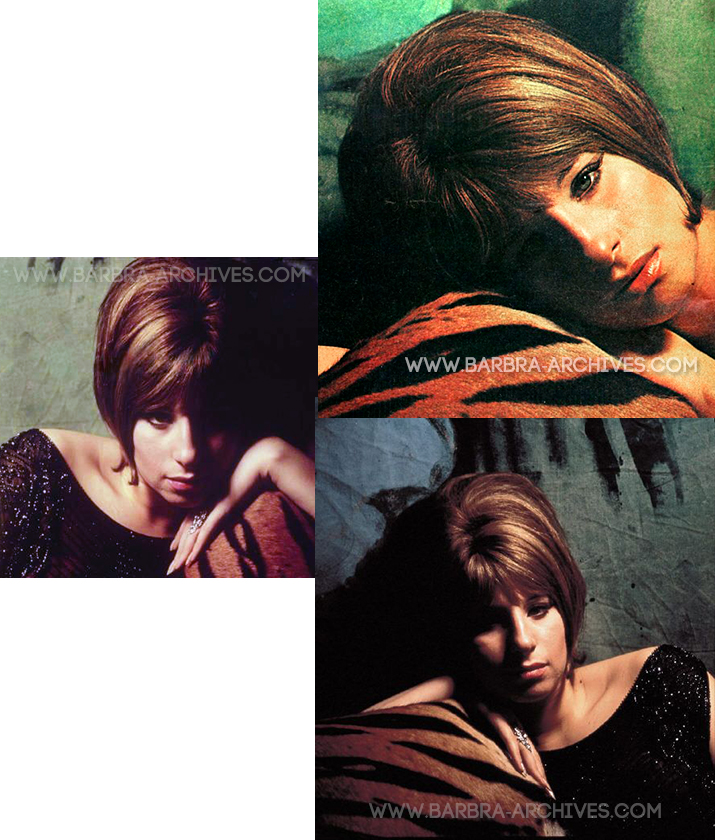

Outtakes of Cover Photo