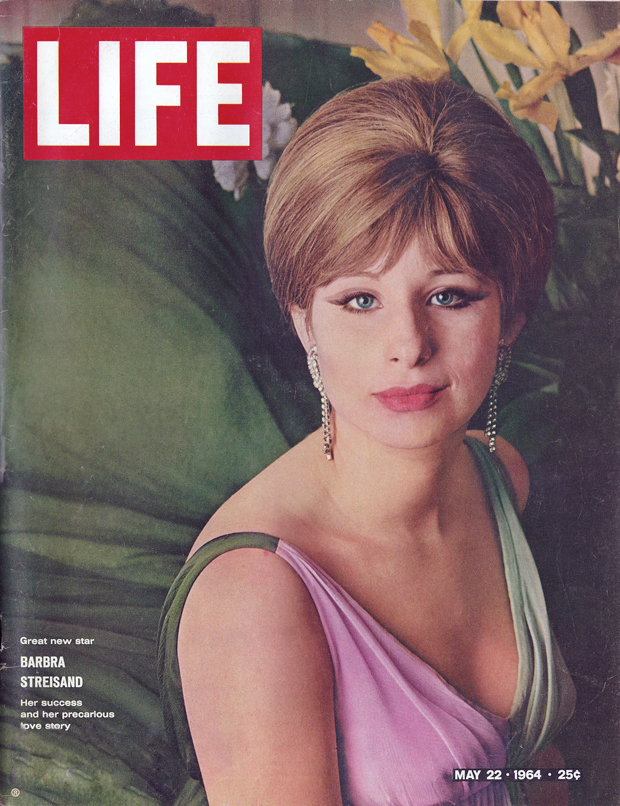

Life Magazine

May 22, 1964

A born loser's success and precarious love

by Shana Alexander

Cover Photo, Inside Spread Photo by Milton H. Greene

It is possible to divvy up humanity a lot of ways—rich and poor, black and white, young and old. Another way is winners and losers, and seen from this angle Barbra Streisand started from about as far back as one can get. When, five years ago, 16-year-old Barbra decided to leave Flatbush, invade Broadway and aim for the stars, she had every mark of a loser. She was homely, kooky, friendless, scared and broke. She had a big nose, skinny legs, no boyfriends, a conviction that she was about to die from a mysterious disease, no place to sleep but a portable folding cot and, worst of all, a supersensitive brain which could exquisitely comprehend precisely how much of a loser she actually was. Things being how they were, there was only one possible way out for Barbra: straight through the top of the tent.

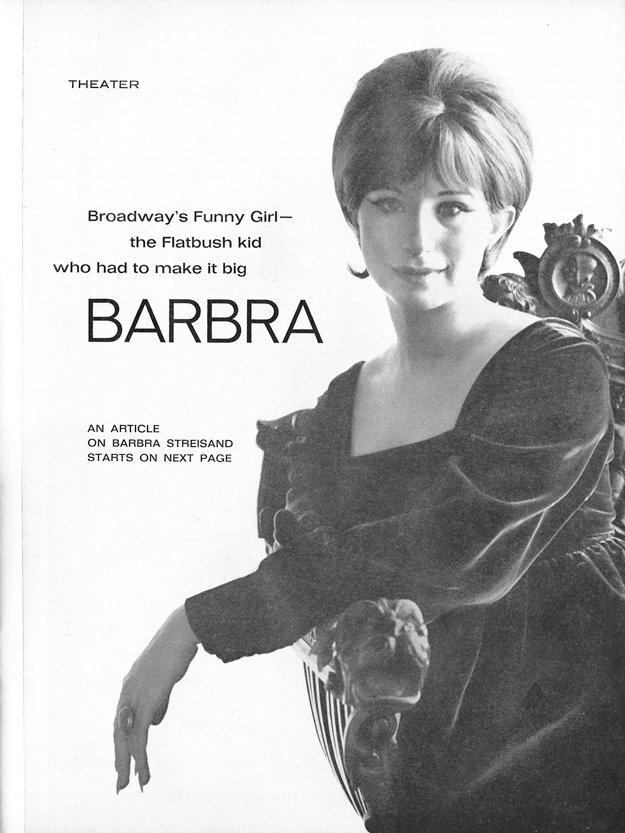

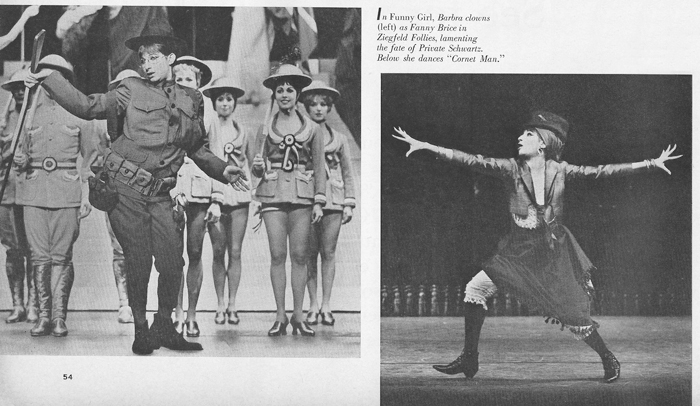

Funny Girl is the proof that she made it. When Barbra opened on Broadway as the star of the new musical comedy last March, the entire, gorgeous, rattletrap show-business Establishment blew sky high. Overnight critics began raving, photographers flipping, flacks yakking and columnists flocking. Thanks to such massive stimulation the American public has now worked itself into a perfect star-is-born swivet.

Today Barbra Streisand is the drummer boy leading the charge, Cinderella at the ball, every hopeless kid's hopeless dream come true. Having effectively routed the winners, that puny minority of beautiful girls and successful men, she now stands as the fervent heroine of Everybody Else. Her show is a sellout and her albums are a smash. Even more remarkable is the sudden nationwide frenzy to achieve the Streisand "look." Hairdressers are being besieged with requests for Streisand wigs (Beatle, but kempt). Women's magazines are hastily assembling features on the Streisand fashion (threadbare) and the Streisand eye make-up (proto-Cleopatra). And it may be only a matter of time before plastic surgeons begin getting requests for the Streisand nose (long, Semitic and—most of all—like Everest, There).

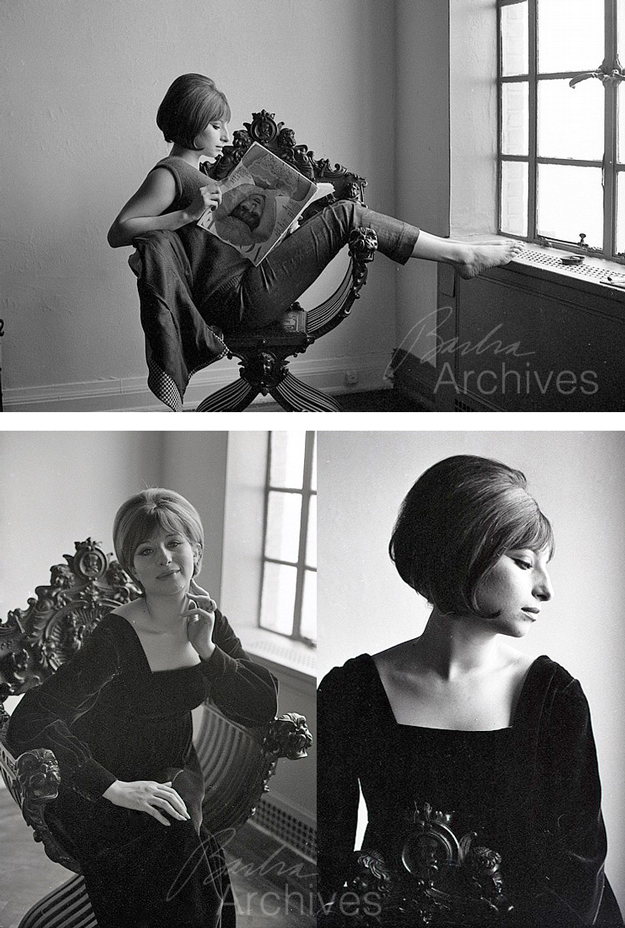

Like the nose, the girl is unique. For one thing, she reverberates between extremes. She appears to be at once both beautiful and ugly, rough and smooth, graceful and awkward, childlike and of immense age. In the recent journalistic frenzy to commit Barbra's appearance to paper, she has been likened to an amiable anteater, an ancient oracle, a furious hamster and an elegant Babylonian queen. At varying moments she resembles them all. But the surprising, stunning supertruth is that there are times when she does become incredibly beautiful. Stand beside her at her dressing-room mirror backstage, so that you can see simultaneously both the real girl and the reflection in the glass, and the truth about copper helmet of hair, her gliding motions, the long, slow fullness of her body movements. Offstage she is appealing for opposite reasons: she is rough, timid, unformed. For, of course, Streisand is not just a huge dollop of talent. She is also a 22-year-old girl, a young bride and very vulnerable indeed.

The great magnitude of Barbra's talent was apparent in chrysalis form the first time she sang on any stage professionally four years ago, in a Greenwich Village nightclub. "This girl had to become a great star. Anybody could see it," observers of the historic occasion have since maintained. Anybody could see, too, that this girl was already a five-star eccentric. For her debut she wore a $4 dress salvaged from a thrift shop, a frayed Persian vest, clown-white make-up, an English sheep dog coiffure, out- size Minnie Mouse shoe buckles, and the song she chose to sing was "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" But eccentricity could not disguise her talent.

Eventually she was signed to do two specialty numbers in the musical comedy, I Can Get It for You Wholesale. One number, "Miss Marmelstein," stopped the show. Records, TV and nightclub work followed in furious profusion and, by the time Funny Girl opened, Barbra was already the top female LP seller in the country. In all, dozens of agents, managers, teachers and taste-makers played minor roles in bringing Barbra Streisand to her present boiling point, for in reality there is no such thing as an Instant Star. Stars are made, not born. But the one person who really stirred up the marvelous, original concoction which is Barbra Streisand today, who not only homogenized the raw talent and the growing girl, but who a thousand times has saved the whole brew from dribbling away into a vain splatter of nerves and doubts, is Barbra's young husband, a wry, mop-headed, accomplished singer-dancer-actor named Elliott Gould.

The private story of Mr. and Mrs. Gould is less sure-footed but oddly more comprehensible than the public success story of Barbra Streisand. It is a precarious love story. But unlike the old-fashioned romance between Fanny Brice and her gamblin'-man husband which forms the creaky plot of Funny Girl, the Goulds' story is as contemporary as a TV dinner.

It began at the auditions for I Can Get It for You Wholesale. Elliott had just been cast as the leading man when Barbra suddenly materialized, like some Halloween spook, as Miss Marmelstein. Elliott was 23, Barbra was 19. Each was on the brink of stardom. Off stage, each was painfully shy. Buffeted by incipient success, they became inseparable. Says Barbra, "We worked together, we lived together, we were not apart for more than one hour. We thought of each other as Hansel and Gretel." But Barbra has her fables garbled. The real prototype for Barbra Streisand is the Ugly Duckling. Elliott was the first person who saw the swan.

"A freak—a fantastic freak!" Elliott remembers thinking. He was slouched in the darkened theater watching the Marmelstein auditions when, over the footlights, clambered a strange-looking, skinny creature with long, spiky hair, spidery hands, two-inch nails and purple lipstick. "I sang," Barbra recalls, "and then I sort of ran around the stage yelling my phone number and saying, 'Wow! Will somebody call me, please! Even if I don't get the part, just call!' I'd gotten my first phone that day, and I was wild to get calls on it." That night Elliott phoned her. "You said you wanted to get calls, so I called," he said. "You were brilliant." Then he hung up. They did not meet again until the first day of rehearsals. "Barbra had this satchel bag and tattered coat. She looked like a young Fagin," Elliott remembers.

"I thought he was funny looking," says Barbra. "He gave me a cigar. He was like a little kid. One day at rehearsals I saw the back of his neck and—I just liked him."

Elliott was too shy to ask for a date, but he started walking Barbra to the subway after rehearsals. "She scared me, but I really dug her. I think I was the first person who ever did."

Barbra admits that now. In high school she'd had a 90-plus average, no dates, no friends. At home she used to lock herself in the bathroom, smoke, glue on false eyelashes, throatily emote TV commercials in the mirror, and dream of becoming a Great, Great Star. "I hadda be great. I couldn't be medium. My mouth was too big."

One night Elliott took Barbra to a horror movie about giant caterpillars that ate cars, and then they went to a Chinese restaurant. About 2 a.m. it began to snow. "We were walking around the skating rink at Rockefeller Center when Elly chased me and we had a snow fight. He never held me around or anything, but he put snow on my face and kissed me, very lightly. It sounds so ookchy, but it was great. Like out of a movie!"

"She was the most innocent thing I'd ever seen, like a beautiful flower that hadn't blossomed yet. But she was so strange that I was afraid," Elliott recalls.

The first time Elliott saw Barbra cry was a few weeks after then- snow fight. She fancied he was paying attention to another girl in the show and refused to talk to him. That night he wandered the city and used up a pocketful of change calling Barbra's flat. Each time he called, she hung up. Finally he went to bed. "About 4 a.m. my bell rang, and she was standing there like a little orphan child, in her nightgown, tears streaming down her face."

To cheer her up, Elliott told Barbra she reminded him of a combination of his two favorite people: Sophia Loren and Y. A. Tittle. He took her home, but when he smelled where she lived—above an East Side fish restaurant—he refused to go upstairs.

"The hallway stunk," says Barbra, "but I didn't care. For the first time in my life I had my own apartment." Soon she was sharing the apartment with Elliott. It was a bizarre little nest.

"The only window looked out on a black brick wall," Elliott recalls. "We used to eat on the sewing machine. A big rat named Oscar lived in the kitchen."

The tiny rooms were littered with the flotsam Barbra had scavenged from thrift shops. Feather boas, rusty fedoras, coats of ape and skunk, empty picture frames hung from the walls. The curious furnishings included a battered dentist's cabinet filled with shoe buckles and an apothecary jar of faded beauty marks.

"Her taste is just wild, it's genius, really," says Elliott. At any rate the same taste which was bizarre then is in Vogue today. That magazine ecstatically calls Barbra "indelible" in a recent issue.

Barbra says she was first attracted to the thrift shops by their piles of antique lingerie. "Like right out of old movies!" she marveled, fingering the threadbare negligees of faded satin.

"Who buys this creepy stuff?" she asked herself. One day came the answer: "Me!"

"I never was a beatnik. I bought that stuff because it was cheap. Besides, I figured, anybody that's rich enough to donate to a thrift shop gotta dress clean, know what I mean? I mean—they're rich enough to take a bath, huh?"

Barbra earns $5,000 a week today but she is still a penny pincher. Last week, backstage, on a day when high-strung Barbra was a bit closer to blowing apart than usual, she and a friend lapsed into a game of make-believe psychoanalysis. In a rich Viennese accent the friend urged, "Zis iss Dr. Kronkheit. Relax and tell me the first thing that comes into your head."

Replied Barbra promptly, "How much?"

During the run of Wholesale, Barbra and Elliott fell into an intense, private way of life. After leaving the theater they would wander up and down Broadway, watch interminable horror movies and play pokerino in penny arcades. Elliott saved up coupons from his winnings to provide their flat with dishes and glassware. They subsisted on grapefruit, brownies, herring, corn soup, and these nibbles became their "special foods." Their staples were TV chicken dinners and coffee ice cream bricks—still Barbra's favorite foods today.

Holed up in the cluttered flat, they played endless games—Monopoly, chess, checkers, cards— and made wild plans. Barbra decided they should study Greek or Latin "so we could speak a secret language nobody else could understand." They swore never to be apart on their birthdays, and they shopped for special presents. Elliott gave her a white marble egg she still carries. She gave him a gold cup inscribed "First Annual Alexander the Great Award," in honor of his favorite historical personage, the youngest man to conquer the world. Barbra hid her sentimental side from all others. Once Elliott gave her a rose for her birthday, and when Barbra's mother asked what his present had been, Barbra replied, "Cash."

After Wholesale closed (Dec. 8, 1962), Barbra's blazing success made their secret life more and more difficult. "Our first separation was hell," Barbra says. She had to go to California for seven days to do a Dinah Shore TV show, and she cried every day. The next major separation loomed when Barbra and Elliott both were offered leads in a London production of On the Town. Elliott wanted to go. Barbra's manager advised her against leaving the country at this critical point in her career. The couple decided the time had come either to break up or get married.

"It was like we shook on it. Let's get married—glop! So we did," says Elliott. Barbra was singing at the Eden Roc Hotel in Miami. Her manager and her business manager were witnesses. "Two days later," says Elliott, "they pushed me onto the plane to London." The separation was painful, and things have been more or less painful for the Goulds ever since. "We live day-to-day," says Barbra. Elliott adds, "To say I love Barbra—that's obvious. Otherwise I couldn't have stood it. I know the traps, I know the wounds, and I've decided it's worth it to wage the battle. People say theatrical marriages don't work. Our battle is especially difficult because we're real people, not just two profiles, two beautiful magazine covers. We really love one another."

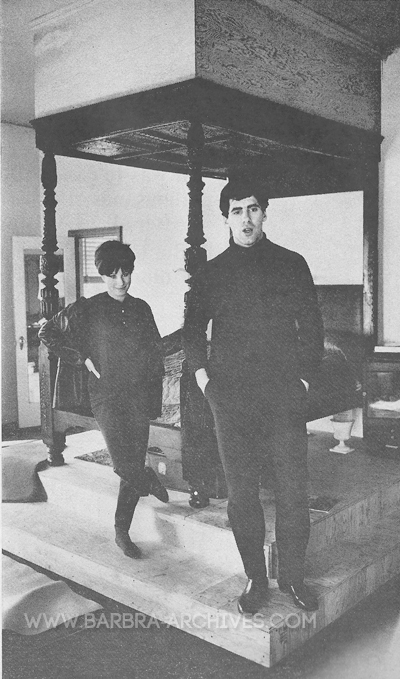

The vortex of the Goulds' wildly spinning, success-ridden life today is not their careers, nor even their marriage. It is a duplex penthouse, terrace-ringed, shimmering 21 stories up above Manhattan. They are encamped there like a pair of gypsies in a half-wrecked enchanted castle, leading a grandiose, accelerated version of the same raggle- taggle life they led over the fish restaurant. The kitchen has been half papered in patent leather, but the refrigerator is still stocked with TV dinners and ice cream. The closets are choked with mountains of thrift shop debris, and the Goulds are in an eternal dither of interior decorating.

Barbra glides down the winding stairway from the tower bedroom wrapped in a padded, lemon silk robe, looking as stylized and elegant as a Japanese empress, the mannered effect jarred by a kitchen spoon of tomato-dripping stew in her slender hand. She nibbles. It is a terrible visual shock, the prosthetic-looking steel spoon terminating the beautiful body line of her upraised arm. A decorator springs forward with a lapful of swatches.

"Which flocking for the foyer?" he pants.

"Mayonnaise, garbage bags," says the Japanese empress, scribbling a shopping list. She points to a swatch. "The oohky brown one," she commands. She wanders to the dining room, steps over an over- turned, broken antique French gilt chair. She crouches down to look at a painting on the floor, and stew drips onto one of its corners. "There's been no intermediate stages in my life," she tells the visitor. "See, like I went direct from a railroad flat to a duplex penthouse. Didja see the bed yet? Upstairs? It's the first thing that we bought. Fabulous. Hey, wait a minute. I want to show you what Cue wrote about me." She dashes upstairs to get the magazine, rushes back, pants, "I love this where it says, '. . . she manages to sound like a vintage phonograph record. . . .' I love that. It shows he dug me!"

It seems incredible to the visitor that Barbra should single out this one line, yet be utterly unimpressed by the critic's opening sentence: "Magnificent, sublime, radiant, extraordinary, electric—what puny little adjectives to describe Barbra Streisand!" But the lapse is characteristic of Barbra today. Her success is so overwhelming that she cannot comprehend it. What 22-year-old girl, after all, can cope with fan mail from Frank Sinatra? After seeing her show he wrote her, "You were magnificent. I love you." It is easier to concentrate on wallpaper.

Barbra never looks at her name in yard-high letters above the Winter Garden theater. She is shy with the fans clustered around the stage door, shier still at the glittery celebrity parties she and Elliott are now expected to attend.

Her opening night on Broadway was unquestionably the single biggest personal triumph show business has seen in years. Yet, says Elliott, "Opening night was a disaster for Barbra. People were pawing her, sticking mikes down her bosom, telling her things she couldn't believe." "It was almost depressing," says Barbra. Of course, if the entire first night audience had fainted, and Barbra had arrived at the Rainbow Room in a pumpkin coach, opening night still could not have lived up to her Flatbush- born visions. When you really believe in fairy tales, it is always a letdown to have them come true.

Of his own reactions to opening night Elliott says, "I had to realize that Barbra is my woman, but everybody wants her. I have to be above it, because if I'm in it I'm going to get stomped to death."

Despite the howling disorder of her life today Barbra can say: "Chaos bothers me. I'm accustomed to it, but it bothers me. I would like to have a regular routine—get up in the morning in my beautiful bed, ride horseback in Central Park, have a great English breakfast, lots of great meats. Then have lessons in something, maybe Greek, lie on my chaise and read some great books in Greek . . . and then tea. Yeah! A great tea, with pastry made by my own special chef. . . . Then a great dinner, by my Chinese chef. ..."

Barbra can run on like this for hours. Her personality is changing with such speed that it is often harrowing to be with her for long these days. Her defense is to keep talking, switching subjects. She still wears the thrift shop clothes, but are they outlandish or are they chic? At the recording session for the cast album of Funny Girl, she stalked into the vast studio wearing smudged white Capri pants, knee-high crocodile boots, a flowing, fur-collared cape and a hat like a bishop's miter. She was an hour late, but she entered the roomful of irritable musicians with the confidence of Clyde Beatty. You could almost see the cane chair and the whip in her hand. She took no warm-up, and when she sang she was the complete pro. Yet, as she was listening to the playback, she jammed her thumb in her mouth, her tummy stuck out and her bulbous, lofty hat flopped cockeyed over one ear. It was easy to understand what Elliott means when he says, "I often think of Barbra as 46, going on 8."

When she isn't recording, or being interviewed, or performing, or sleeping, Barbra's consuming passion is antique shopping. She no longer is limited to thrift shop purchasing, but she attacks the high- priced wholesale antique district with the same avidity. When possible, she likes Elliott to accompany her on these forays. It is often possible. He has not been over- worked professionally of late. He co-stars with Carol Burnett in a TV version of Once Upon a Mattress; this winter he staged a new nightclub act for Anna Maria Alberghetti; and recently he flew to Jamaica for a movie role. A few days before leaving he and Barbra, their decorator and a couple of friends piled into a taxi for another onslaught on the antique marts.

Passing a dusty shop window, Barbra screams with delight, "Look, Elly! It's a penny gum machine!" The Goulds have one like it at home. They decide to go to a horror movie that night, after the show, and begin talking about the good old late-night movie days, proud of their arcane, shared knowledge of old films.

"Know who Blackie Norton is?" Elliott asks.

The name does sound familiar.

"That was Clark Gable's name in San Francisco!" he says triumphantly. Barbra looks immensely pleased. But it is getting tough: the Goulds have fewer and fewer shared memories these days.

At the antique mart they pile out of the taxi, and Barbra plunges into the dust-covered warehouse, trailed by Elliott, the decorator, the friends. "What's this? . . . What's that? . . . How much? . . . Divine!" she shouts, dashing from lamp to chair to chest, grabbing up bits of molding, scraps of hardware.

"Divine!" echoes the decorator. "Great!" scream the friends.

The strange procession snakes out of one warehouse and into an equally dusty shop next door. But suddenly the Goulds fancy that the proprietors of this shop don't like them. Maybe the owners, two sleepy-eyed, Levantine types, recognize her. Maybe they don't. Maybe they think she isn't going to buy anything. She stalks out, upset.

"It's a front, Barbra. It's a bookie joint. They're gangsters," Elliott says to soothe her. But already Barbra has dashed into the next shop and is shouting, "What's this? What's that? Divine!" Somehow, in the bargain-hunting melee, Elliott disappears to attend his acting class. He says he'll rejoin the bargain-hunters in an hour. While he's gone, Barbra buys an ornate, antique piano that doesn't play ("It can be easily restored," the shopkeeper assures her) and three enormous crystal chandeliers.

As she passes the "gangsters' " shop next door she rushes to the window, raps on the glass, waves her sales check and shouts to the startled proprietors, "Yah! You thought I wasn't gonna buy, huh? Well, I spent $3,000 next door!"

Suddenly Elliott returns down the street. When he hears about the piano, he is furious. Now the Goulds have a screaming, four-letter fight in the street, hopping in and out of taxis, over curbs, past startled pedestrians, oblivious of decorator, friends, passers-by. Like Fanny Brice, it seems, the only thing that can embarrass Streisand is a bad performance.

How dare Barbra buy a piano, a piano, without consulting him, Elliott demands?

"I did it for us!" she shouts. Doesn't he want them to have a nice apartment? Doesn't he care about their home? Besides, she loves the piano. It is the most beautiful piano she's ever seen.

"It's hideous!" he yells.

"Elly, it has painted scenes on it," she says grimly. What has started almost as a mock-fight, an actors' fight, is no longer fun. Because the fight isn't really about the piano, it's about who is In Charge, and they both know it.

Taxiing back to the penthouse, they don't speak. They fake it through dinner, Barbra goes to the theater and Elliott spends the evening installing hardware. They don't speak all night. The next morning on the telephone Barbra hears from the shopkeeper that the insides of the piano cannot be restored after all. It is Wednesday, matinee day, so she leaves the duplex right after her noon breakfast—brownies and herring. By the time she arrives at the theater she is fairly dripping with guilt because of the way she has treated Elliott. She feels awful. After the matinee as she is sipping tea alone in her dressing room, a florist delivers a curious object. It is a large cactus plant with a single rose wired into its center. The card reads: "Dearest Child, You can always plant flowers in the piano. I'm sorry it doesn't play [signed]—Alexander the Great." Another day does turn out to be gettable-through, after all.

If the duplex is the center of the Goulds' life, the central item of the duplex is an ornate 300- year-old bed. It was the first real antique they bought, and they spend hours discussing how they want it to look. "It should be like the place Desdemona got strangled in," Elliott tells a bewildered upholsterer. Barbra is more specific. The bed already has been mounted on a dais. She tells the decorator she wants the entire bed draped and skirted with olive-gold damask, the top part "draped in, folded, so that it makes a crown, with sort of tassels hanging down, huh?" The decorator nods numbly. "And I want a red fur bedspread." He nods again. She adds that damask curtains should be hung from brass rods mounted between the bedposts "to completely close in the bed like a train berth, see? But you can loop the curtains back to the bed- posts, maybe with khaki velvet ropes, and that's when you see the lace curtains inside..."

"Lace!" shrieks the decorator.

But that's not all. Into the side of the contraption the Goulds want to build a little refrigerator to hold the coffee ice cream. One gets the impression that if ever their fantastic hideaway is completed, the final step will be to nail shut the door, climb into the bed, let down the lace, pull the curtains, watch a horror movie on TV and eat coffee ice cream.

But they cannot keep the curtains closed forever. Each day but Sunday and twice on matinee days, the former Ugly Duckling leaves the penthouse, taxies to the theater, makes her way through the knot of gentle fans—the losers—who wait by the stage door, and puts in her brilliant, blazing, 2-hour marathon stint as the Funny Girl. Barbra has now played the role 67 times and some days she admits she gets bored. "But I hafta do it, like I always did my homework."

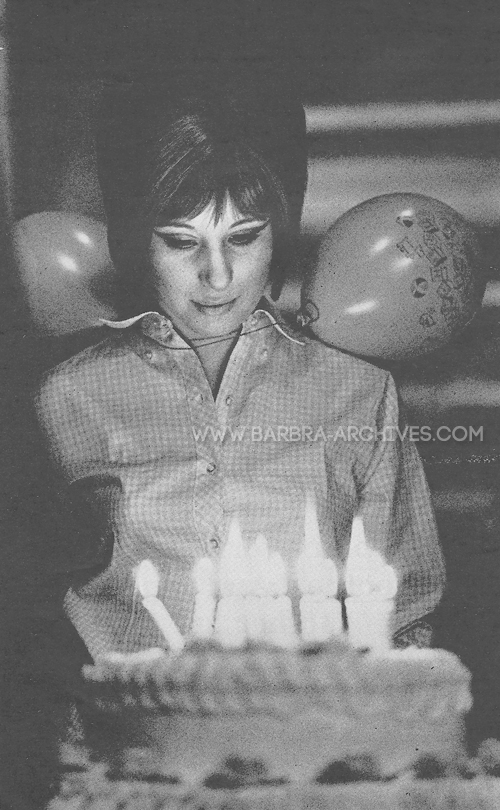

At her 22nd birthday backstage at the Winter Garden, Barbra stares wistfully at a chocolate cake. Elliott was then in Jamaica and could not make the party.

One such time was on Barbra's 22nd birthday last month. Elliott was still in Jamaica for his movie role, and the day loomed lonely. But Barbra has hundreds of friends today: she got three surprise parties. A friend tossed a kids' party "with ice cream and real kids" before the show; her manager gave an elegant supper party afterwards; and backstage the producers provided champagne and chocolate cake for the entire cast. But Barbra's fans staged the biggest bash.

As she was taking her curtain call, a box-seat holder shouted "Happy Birthday!" Another box- holder across the theater took up the cry, and in an instant the entire audience of 1,524 people was on its feet cheering wildly. The orchestra struck up Happy Birthday and Barbra tossed roses over the footlights. It was a heady moment for the theatergoers, but baffling for Barbra. "What does it mean when people applaud?" she says. "I don't know how to respond. Should I give 'em money? Say thank you? Lift my dress? The lack of applause—that I can respond to. It tears me up! But I can never understand why people laugh or cry when I sing. ... So the only happiness I know is real is the happiness I get from eating coffee ice cream."

Show-stopping predicament: should she surrender? In Funny Girl's funniest scene, Barbra turns an attempted seduction into a riot. Invited to an elegant champagne supper for two by her suitor, suave con man Nicky Arnstein, she permits him to ply her with paté. As she vamps him with a fan, she wonders to herself just what would happen if she should surrender to him ("Would a convent take a Jewish girl?").

END

Related: Funny Girl (Broadway)

NOTE: A condensed version of this article was included in the August 1964 issue of Readers Digest Magazine. [pictured below]

Alternate Photographs by Milton Greene

[ top of page ]