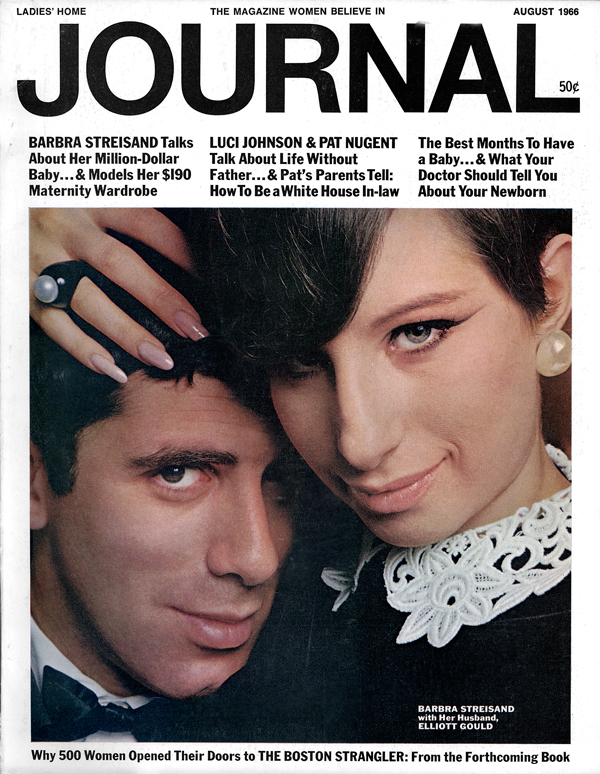

Ladies Home Journal

August 1966

BARBRA STREISAND TALKS ABOUT HER “MILLION-DOLLAR BABY”

By Gloria Steinem

Photographs by David Montgomery

“New Role For Barbra” by Trudy Owett, Fashion Editor

Barbra Streisand's hair by Frederick Glaser

"This pregnancy is like a God-given thing," said Barbra, "and the timing couldn't have been better. I was beginning to feel like a slave to a schedule. Pretty soon I'll have nothing to do but cook and be pregnant five whole months. I can't wait!"

She would have earned more than a million dollars merely from one concert tour that has now had to be drastically curtailed, and the temptation was too much: Everybody immediately talked about a Million-Dollar Baby. "Why do they say that?" asked Barbra. "I mean, why must they measure everything in money? The most important thing is not what got canceled but that a healthy baby is born.

"I always thought that having babies was for other people," she went on, "but not for me." We were having tea before her evening's performance of Funny Girl in London, and the local critics—like those of every city she has ever appeared in—had just received her with raves that might have been written for Frank Sinatra and Sarah Bernhardt combined. But the time she spoke of was not the triumphant, star-spangled Now. (A very short Now at that: from a $50-a-week obscurity to multimillion-dollar status as, to quote a critic, "a living legend," took just five of her 24 years.) It was the homely, awkward, often anguished time of her growing up—a very lonesome Then.

"I was kind of a loner," she explained, "a real ugly kid, the kind who looks ridiculous with a ribbon in her hair. And skinny. My mother wouldn't let me take dancing lessons because she was afraid my bones would break; she was always shipping me off to some health camp. I would try to imagine my future, like other kids, but I couldn't, it just stopped. There was a big blank screen, no husband, no children, nothing. I decided that meant I was going to die—I wasn't being melodramatic or anything, I really believed it, and I would think, 'That's too bad, because I really could have done things.'"

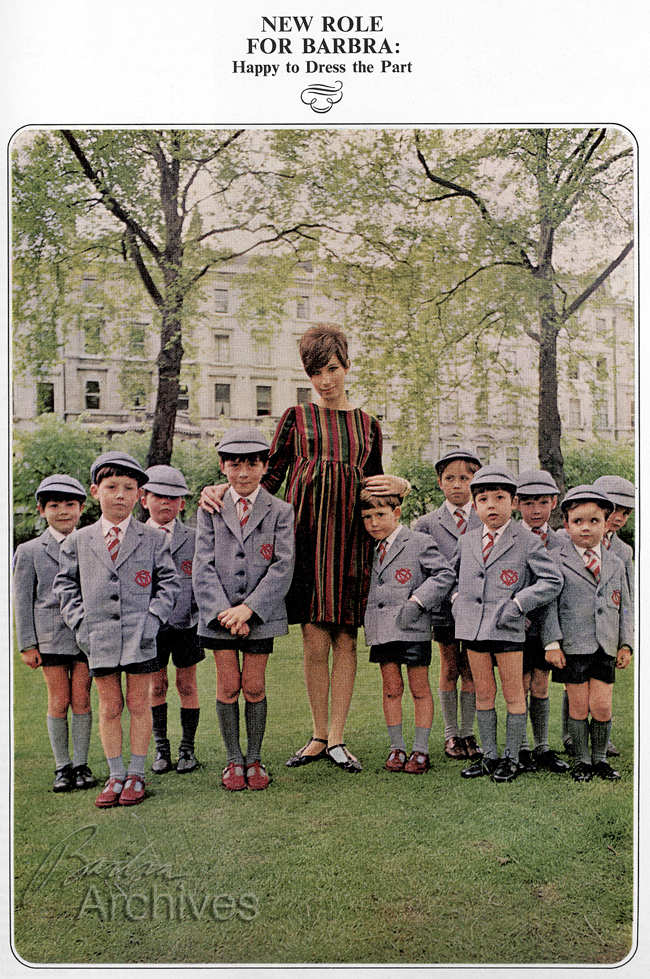

In a few months, Barbra Streisand plans to play the most important role of her spectacular young life. Barbra's expecting a baby, of course, and having lots of fun while she waits. Barbra loves clothes (she's on the best dressed list!), so part of the joy of being pregnant for her was selecting a marvelous mother-to-be wardrobe. Here's where the Journal entered the picture. We picked some of our favorite maternity clothes, flew them to London, where Barbra was appearing in Funny Girl. Barbra, in turn, picked her favorites from the group. Here they are on these pages.

(Photo, above): At Ennismore Gardens, Barbra poses with little schoolboys. She wears a striped cotton-velveteen dress by Ma Mere, 6-14, $45. Shoes, I. Miller Galleria.

As it strange to think that her child will have a life so different from her own lower middle-class one in Brooklyn? "Well," she smiled, "I can't suddenly get poor for her, or him, can I? But I don't want a child who has nothing but toys from F.A.O. Schwarz. Kids like simple things to play with: a piece of paper, a walnut shell. They should be dirty and basic when they want to be. I don't want to make her a kid brought up by the book. I think that if I can give her confidence and love and the feeling that she's wanted. I'll be able to be honest, too; a person as well as a parent.

"That's the most important thing; that she feels loved and has both parents." Barbra's own father, a teacher of English and psychology, died of a cerebral hemorrhage when she was 15 months old and her brother, Sheldon, was nine. She looked thoughtful, as if remembering the years when her mother worked as a bookkeeper to support two children, and Barbra's bed was also the living-room couch. Friends say that she often asks questions about the father whom she doesn't remember, that she is proud of his promising career as an educator, and feels that her own life would have been different, not lonely, had he lived.

"That's the greatest thing about having a baby," she said, smiling again. "I get so self-involved, too focused on my own problems. But when I think of what's growing inside me, it's a miracle, the height of creativity for any woman. I used to dream about having a child, but it just didn't seem possible that it could happen to me; it seemed completely foreign. I even thought about adopting one. And now here I am and it's all going on in there. In December there will be a whole new human being.

I've been reading medical books—I've always been fascinated by the way our bodies work: I'm not squeamish about it, or upset by the sight of blood—and it's incredible how it all functions. Each organ has a duty in the process, each part of it set off by complex signals. . . . I'm telling you, it's not to be believed. There must be a God!"

Natural childbirth is definitely part of her plan. Both she and her husband, Elliott Gould, will go to classes in New York this fall. Barbra has already read a book by the Englishman, Dr. Grantly Dick-Read, who pioneered the natural-childbirth movement.

"I can't understand how some women can just say, 'Give me an injection, I don't want to know a thing about it.' I mean, I really wonder about people like that. How can they miss the experience of birth? If they really feel it's some awful thing just to be got over, why do it at all?

"All those stories about how we'd been trying to have a baby for years were ridiculous. If we'd wanted a baby, we probably would have had one. I really think there's something mystical about conception. I mean, there are all those women who can't have children, adopt one, and then have one of their own because they relaxed about it. I'm sure there were many times when I could have got pregnant and didn't because I really wasn't ready yet; I was tense. I was too young.

"At first, I was worried about morning sickness, but I feel fine. The one time I was sick, it turned out to be the flu. And, for the first time in my life, I don't have longings for strange food. Usually, I love to eat, but now I never feel hungry, I just suddenly feel empty, and then I know my system needs food. My only symptom is an excessive need to sleep."

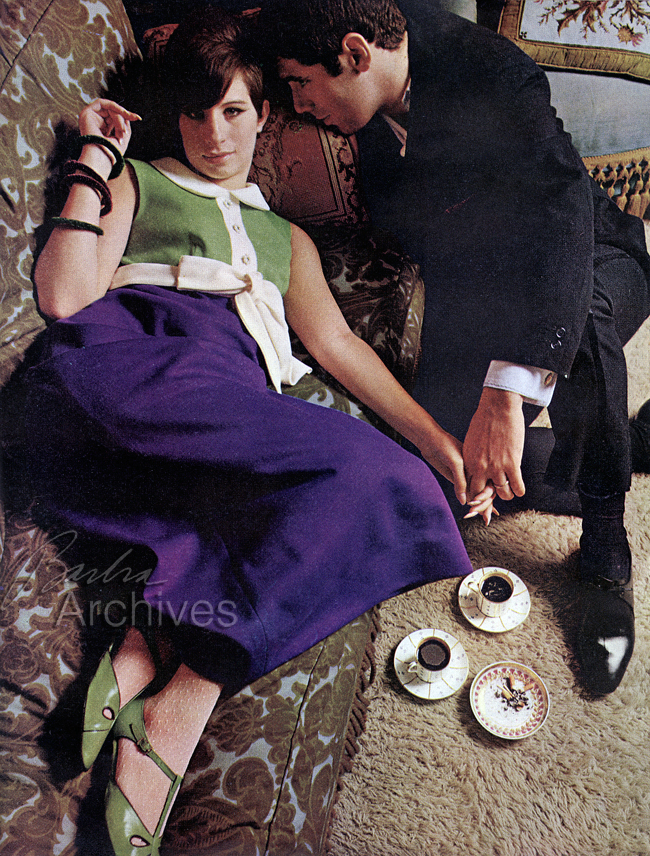

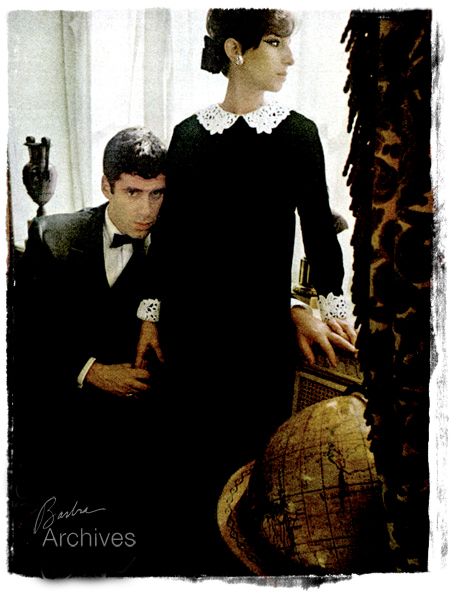

(Photo, above): Having a demitasse, with actor-husband Elliott Gould, Barbra wears an at-home dress by David Loring for Jeanette Maternity. Of bonded Acrilan knit, 6-16, $30. Cadoro bracelets; Evelyn Schless shoes; Beautiful Bryans stockings.

She had an urge to knit in the first weeks, which has now passed, leaving her with an unfinished baby blanket of orange, wine and pink. Her dresser is knitting on it while Barbra is onstage.

As for the name problem, that is nearly solved. "If it's a boy," said Barbra, "we'll probably call him Jason Emmanuel: Jason just because we like it, and Emmanuel because it was my father's name. For a girl, we're thinking of Samantha. It can change to suit her personality: Sam if she's adorable and kooky, Emmie if she's more sweet and serious, or the whole thing, Samantha, if she's exotic."

Elliott — "Elly," as Barbra calls him — was in New York on business that day, but would be back in a few days. The courtship which began when he was the talented, 23-year-old star of I Can Get It for You Wholesale and Barbra was a 19-year-old novice, has become one of the world's best-publicised marriages. That it has survived the strains of two careers and Barbra's streak to stardom is a tribute to them both. ("He handles it all very, very well," said Jerome Robbins, director of Funny Girl. "Elliott is a gentleman.") “To say I love Barbra,” Elliott once told a reporter, "that's obvious. Otherwise I couldn't have stood it. I know the traps, I know the wounds, and I've decided it's worth it to wage the battle. People say theatrical marriages don't work. Our battle is especially difficult because we're real people, not just two profiles, two beautiful magazine covers. We really love one another."

Since they met, Elliott and Barbra have been together most of the time ("like Hansel and Gretel," as Barbra once explained) in the face of considerable professional pressures to keep them apart; probably he was the first person to really understand her, to stamp his image on the blank screen that she had seen as her future. ("She's fragile and exquisite," Elliott explained, "she needs taking care of. She liked me, and I think I was the first person who liked her back.") But scurrying back and forth between television shows, concerts, movies, and all their separate commitments is not easy. They see the baby as something that will give them roots again.

Barbra's sense of differentness was always part misery, part confidence in her ability to "do things," but, looking at her in an English drawing room, sleekly coiffed and a deserving member of the Best-Dressed List, it was hard to remember that her early suffering had centered around the way she looked. In a world of snub-nosed American cheerleaders, she was clearly a misfit. She daydreamed, went to the movies and imagined herself on the screen, locked herself in the bathroom to carry on experiments with wild hair styles and dark lipstick ("I liked Rita Hayworth," she remembers, "I thought actresses had to be vampy"), and tried to fit into the pretty-girl ideal with "pink and white dresses with ruffles and lace—things I never should have worn."

At 14, she was an honor student at Erasmus High School in Brooklyn, a girl who never went to proms or had a date for New Year's Eve, but she had also made a friend. "One day I met this girl named Susan," she said, "who wore white makeup and kooky clothes. I liked her immediately." Susan helped to get her out of ruffles and free her sense of style ("I didn't sulk because I wasn't gorgeous," said Barbra, "I dressed wild to show I didn't care"), and, two years later, after graduating from high school, she left Brooklyn and any desire to be "ordinary, pretty like Shirley Temple," behind forever.

Still, even by Manhattan standards, she was a secret and very special girl. A member of an acting class that she attended briefly (between unsuccessful rounds of producers' offices and such part-time jobs as sweeping up at an off-Broadway theater) has a vivid picture of her as "always late, very intense, wearing a coat of some immense plaid, and eating yogurt." Even her few close friends had no idea that she could sing until she got her now-famous $50-a-week job at a Village nightclub. Singing had been another part of her differentness, her private world, something she did alone on the roof of her Brooklyn apartment house, or sitting on the front steps on summer evenings. In fact, even the singing job seemed a compromise. She wanted to be an actress. "I knew I was good," she said stubbornly, "but no one would let me read till I had experience, so how could I get experience? Besides, I wasn't the ingenue type those casting creeps were looking for. I could have changed the way I looked, had my nose fixed or something, but I just couldn't. That wouldn't have been honest, right?"

Finally, singing in a nightclub, her unique looks and style and talent began to pay off. In a middy blouse, shoes with enormous buckles, and neo-Cleopatra eye makeup, she sang such off-beat songs as Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf and Happy Days Are Here Again—hardly the "No Business Like Show Business" medley of most young singers. Without a lesson to her name, she surprised everyone with her instinctive musicianship, a sense of gesture enhanced by attenuated, elegant hands, a gift for making any song into a three-act play, and a voice that was reminiscent of many great singers (Judy Garland, Lena Home, Morgana King) while remaining special, and imitative of none. "I couldn't really have imitated anybody," explained Barbra, "because I hadn't really heard anybody. I'd never been to a nightclub until I worked in one."

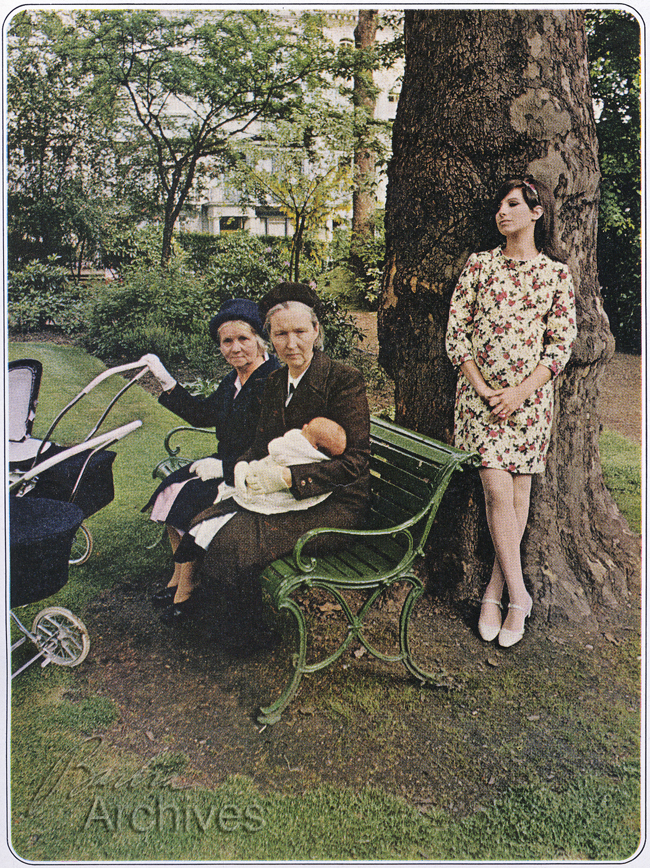

(Photo, above): Quietly observing babies and their nannies, Barbra wears a flowered sleeved smock dress by Storktime. Of sheer bonded wool basketweave, 6-16 $30.

The awkwardness, the price of being different didn't really stop there, but—as she went from the Village club to the Blue Angel, and from there to a show-stopping song in the Broadway musical I Can Get It for You Wholesale—she was compared to Nefertiti as often as "an amiable anteater" and to Cleopatra instead of a ferret. Slowly, she was breaking the cheerleader prototype of beauty and originating her own. By the time she had made several best-selling records, appeared on national television shows, and burst on New York as the star of Funny Girl, fashion magazines were announcing her as "the girl of the ‘Sixties … a unique beauty … a super-star.” All her outré habits of dress and makeup were enshrined as chic, and columnists wrote tributes to her “slender arabesque neck” as well as to her talent.

Different. Different as a star. Different when she was finding her way. Different as a girl, raised in an Orthodox Jewish home. The latter she remembers as an archaic place with little to do with the real world. (“We couldn’t cross our fingers, and we weren't allowed to say 'Christmas.' So as soon as the rabbi went out of the room, I would close my eyes, cross my fingers, and say 'Christmas, Christmas, Christmas' as much as I could.") But she does intend to teach her child about God. "I believe in God. The Orthodox training is outdated, but I think it's an unfair burden to teach a kid nothing; to say, 'I don't know, decide for yourself.' Science isn't everything. No one is ever going to come up with a scientific reason for dying. Organized religion is something I couldn't subscribe to, but it's important that we have a sense of God, a sense of mystery."

But the childhood sense of doom was with her then. ("I still thought I had some mysterious disease, and only two months to live. You really appreciate life," she added soberly, "when you think you're going to die.") And, sometimes, it still is. Each time she gets on a plane, she envisions what would happen, which people would say what if she were to die. After taping her last CBS television special, she flew to Paris, thinking all the way how sad it would be when the TV special was shown and she wasn't there. It happens less and less as she is more and more secure: the screen isn't empty now, and she can see ahead.

It isn't a question of exchanging a career for motherhood. Barbra will go on making records, films (the film version of Funny Girl will begin early in 1967) and television shows. The one medium she has ruled out is the stage: no more Broadway musicals, or any plays unless they are short runs in repertory. ("I'd love to play Romeo and Juliet, but I don't want to be saying the same words every night for years.") The baby will change her life in a deeper, more final way, because it is her link with humanity, her symbol of belonging at last. For a girl who never felt related to her own family ("I used to say, 'OK, Ma, did you find me on a doorstep or what?'"), to her friends or to her neighborhood ("Brooklyn," she says firmly, "was always someplace to get out of"), having a baby seems to be the most real proof of sameness, of relation to others, of continuity, of belonging.

(Photo, above): Like all expectant mothers, Barbra tends to her knitting (and occasional napping), wearing a smock by Stork Style, of cotton rib knit, 6-18, $15. KJL bracelet and earrings; Adler fishnet tights; Julianelli shoes.

If her child is a girl, would she like her to look the same, to have the painful specialness of talent?

Barbra is silent for a while. "I know that my childhood, everything I went through, is important to me, to art. It doesn't matter how she looks; she will be partly Elliott and partly me, but still herself. But I don’t think I’d like to watch her go through exactly the same thing; no. Art isn’t everything. Love is more important.

But, should her daughter be the exact image of Barbra, she would no longer be thought homely. Barbra Streisand has changed the bland, pug-nosed American ideal, probably forever. “She looks just like her mother,” everyone would say. “She’s beautiful.”

A Monthly Report From, By, And For the Younger Journal Set

By Margaret Kadison

If you're a Barbra Streisand fan (and who isn't these days?) you'll be interested to know that Barbra has a 15-year-old half-sister named Roslyn Kind. Roslyn, who has a wonderful singing voice of her own, once thought she wanted to be a lawyer, but recently decided that she, too, would like a career in show business. Friends say her imitation of Barbra is letter-perfect. Where Barbra is known for her kooky clothes, Roslyn is conservative; where Barbra is mercurial, Roslyn stays on an even keel. Otherwise, the girls are amazingly similar — in which case, we'll probably be hearing more about Roslyn soon. For lots more about Barbra, see pages 60-64 in this issue.

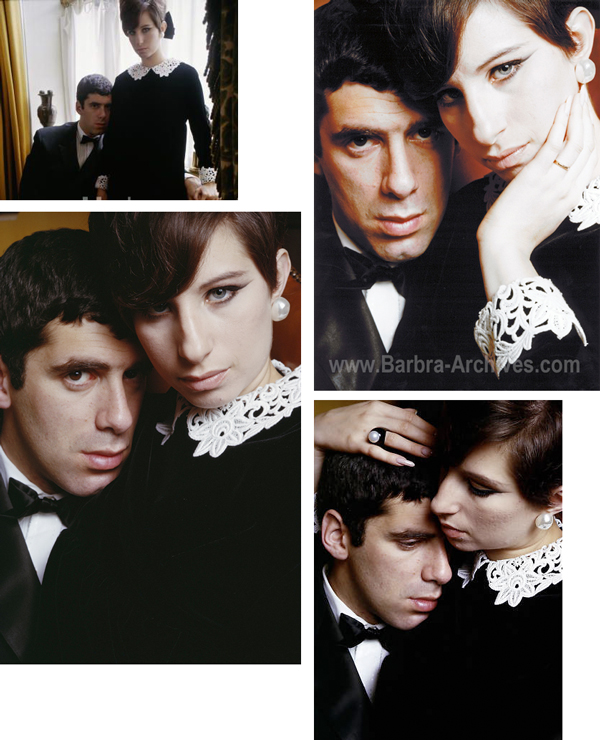

Alternate Photographs by David Montgomery

The photo below, shot in 1966 during the session in which Elliott Gould and Streisand posed for David Montgomery, appeared in Ladies Home Journal (Aug. 1969) accompanying an interview with Gould (“Funny Girl and Me”).

More outtakes by David Montgomery:

End.

[ top of page ]