A KOOK FROM MADAGASCAR

High Fidelity, May 1964

Miss Barbra Streisand is very much a nonconformist (note that first name) and very much a success.

By John S. Wilson

THE MOST METEORIC RISE in the field of popular music since that of Fabian the rock 'n' roll singer has been achieved by a tough, shy, positive, insecure, plain, luminous girl from Brooklyn named Barbra Streisand. Fabian was invented by a crafty Philadelphia agent; Miss Streisand invented herself.

Consider: Less than three years ago, at the age of eighteen, Barbra Streisand made her first attempt to sing, as an amateur in a Greenwich Village bar. This year, after a single appearance in a minor role in a Broadway musical, she is the star of one of the season's major productions, Funny Girl.

Two years after her first professional engagement, for which she received $125 a week, her fee for a single night's work became $8,000.

Her first recording, an LP released a year ago, immediately became a best seller; her second, issued last fall, shot into first place on Billboard's chart of LP sales; for several weeks both discs were among the top ten on this list and both are reputed to be approaching half a million in sales (this, at a time when female singers are supposed to be having a hard time in the pop field).

The protagonist of this fantasy-made-fact has no musical background, had never been in a night club until she appeared in one as a performer, and turned to singing only as a means of making the theatre (which had rejected her as an actress) pay attention to her.

In a matter of mere months she has drawn a kind of acclamation that most performers would consider fitting reward for years of hard effort. The composer Harold Arlen has drawn on memories of Helen Morgan, Fannie Brice, Beatrice Lillie, and the paintings of Modigliani to describe his reactions to her. "Her potential is unbelievable," he says. "The only thing she has to do is pull in her oars a little. She's too intense. But that will come in time." To a fellow vocalist, Carmen McRae, she is "one of the most fantastic singers to come along in years." Miss McRae continues: "I like this kind of singer because she's trying to tell you something. If you don't get the message, you're a complete idiot. And she has musicianly quality and sings in tune— let us not forget to include that!"

Jule Styne, who wrote the songs she sings in Funny Girl, calls her "a unique and ingenious talent" who "makes every song sound like a well-written three-act play. At the beginning of a song, she establishes her character. Next, she creates a conflict (making all the lyrics mean so much more than they seem to). Then she reaches a tremendous conclusion — so that, even after hearing only one song, lasting only a few minutes, one is completely overwhelmed."

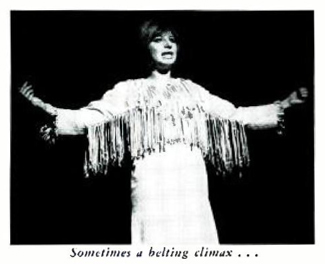

Moreover, Miss Streisand achieves these results in night clubs and on records with songs that are frequently not the kind to which such a description as Styne's would plausibly apply. There is Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?, for instance, which she sings as though it were a fast-moving adventure story embellished with "ha-hoos" that are part Valkyrie and part Beatrice Lillie and given an ending that is out of the Keystone Kops. And there is Happy Days Are Here Again, done at a slow, dreamy tempo moving from blandness to breathy sexiness to an all-out, belting climax.

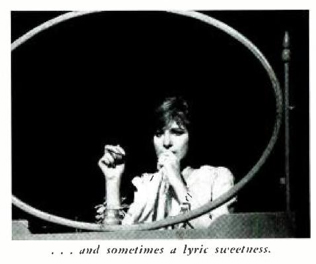

The unexpected is only part of her ammunition, though. Many of her songs convey a strong emotional quality, whether the lyrics are inherently moving — as in Arlen's Like a Straw in the Wind and Much More (from The Fantasticks) and When the Sun Comes Out — or whether they are as contrived as those of My Coloring Book, which she raises to a level approaching art song. Her voice often has a beautifully pure and direct quality too, a sweetness that brings a folk song feeling to A Taste of Honey or Who Will Buy?(from Oliver).

Yet for all the emotion the voice evokes, the songs are delivered with singularly little physical histrionics. Miss Streisand stands there — a rather tall girl with tawny hair, a long nose oddly humped part way down, eyes like those of a Siamese cat, wearing a simple, long, high-waisted dress, her arms at her side -and she sings. Just sings.

Between songs she may stretch, grimace, chat about anything that occurs to her, or suddenly throw out a brief bit of lyric: "You better not shout, you better not cry, you better not pout, I'm telling you why - Santa Claus is dead!" The old song, Mississippi Mud, crosses her mind: "People gather round and they all begin to shout: Eccchh! Mud!!"

IN THE EARLY STAGES of her success, Miss Streisand seemed to be in danger of becoming noted more as a "kook" or eccentric than as a singer and entertainer. The rebellion against conformity apparently typical of her alleged "kookiness" was pinpointed in the thumbnail biographical sketch which she gave to The Playbill and which was printed in the program of her first Broadway show, I Can Get It for You Wholesale: "Born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon; she attended Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn . . . ."

Nobody questioned this until Miss Streisand proved to be a show stopper in Wholesale, the one bright spot in an otherwise disappointing production. Then it became known that she was actually horn and brought up in Brooklyn. The Playbill protested and asked for a corrected biography. Miss Streisand refused. "Who's interested that I was at the Malden Bridge Playhouse? I told them to print a blank space. I hoped they would, but the show closed before the issue was settled."

Miss Streisand's reputation as an oddball was fed by her manner of dressing — she habitually wore heavy black tights in public, and performed in a costume described as a "gingham tent" — so loosely voluminous that she was frequently reported pregnant. Appearing on Mike Wallace's television interview program, she delivered a vehement tirade against milk. The story got around that when she had applied to the Actors Studio and was asked to name her favorite actress, she bridled at giving a fashionable answer (Geraldine Page, for instance) and declared, according to one version, for Mae West, or, according to another, for Rita Hayworth. Whatever the reply, she was turned down.

She rebelled against advice of any kind: she refused to have her nose straightened or shortened; she refused to use more conventional material; she refused to open her act with the traditional uptempo number. "I like to open with a ballad — which I was told was all wrong — or with something that arrests audience attention," she has explained. "Uptempo songs are not important, and I think the first moments on stage are very important."

Miss Streisand is unconcerned about the surprised reactions that her attitude has elicited. "Anything people don't understand," she says, "they label a 'kook.'"

One aspect of her seeming "kookiness," however, stems from deep personal uncertainties. During the nine months run of I Can Get It for You Wholesale, she was late thirty-six times, a record which led to two warnings from Actors Equity. "I'm always late," she admitted. "It's a fear, a lack of sureness because of the pressures of what people expect. In your anxiety to get there, you flounder. You're never ready, never just right."

"When I first started singing. I'd dash into the club three minutes before I had to he on, drop my coat, and run on the stage, sometimes with my make-up only half on. Being thrown on stage was the only way I could get there. But once I was on, I could think very, very clearly. I felt calmer on stage than in real life. On stage, things make sense. In life, they don't. When you're performing, you're not rushed. You can take your time and people just have to wait for you."

Barbra Streisand (the spelling of her first name is an instance of partial rebellion: she hated the name but did not want to drop it so she changed it by leaving out an "a") is the daughter of a high school teacher who died when she was fifteen months old and a mother who worked as a bookkeeper and maintained a strict kosher household. As a child, she "had these dreams of being a star, being in movies, but in Brooklyn I always felt like a character out of Paddy Chayefsky."

AT THE FIRST opportunity — when she had graduated from Erasmus Hall High School at seventeen with a 93 average and a medal in Spanish — she got out of Brooklyn, moving to Manhattan where, for a while, her most crucial possession was a portable cot which she lugged to the apartments of friends who gave her temporary shelter. She studied with Allan Miller, a dramatic coach who was one of the first people to see through the disconcerting exterior presented by this determinedly nonconformist girl. Mr. Miller remembers in particular an improvisation she did of a chocolate chip melting in an oven. "It was beautiful," he recalls, "so tender. We saw Barbra — not clunking around with big feet and bony arms — but as she felt in her imagination."

Others were not as perceptive.

"I was told that if I was going to he an actress," she said recently, "I'd have to make the rounds, knock on doors, sell myself. This was so unreal to me. I made the rounds for two days. It was winter. I was wearing heavy black tights. People looked at me as though I was nuts. I'd say, 'Look, you'd better sign me up, I'm terrific.' But they wouldn't let me read. How can they tell anything if they won't let you read?"

Faced with what seemed a blank wall, she renounced the theatre and declared, "They'll have to come to me." In the summer of 1961 she entered a talent contest at The Lion, a bar and restaurant on Ninth Street. She sang When Sunny Gets Blue and A Sleepin' Bee. She won $50 and was offered a week at the Bon Soir, a Village night club, at $125 a week. She stayed there for ten weeks.

"I just sang naturally," she says, in describing how, with no background whatever, she faced up to the problem of becoming a night club singer. "I was given a sort of good voice. I just do what I think is right and don't care about anybody else. I cant stand phony theatricality. I was never biased by someone else's performance because I was never in a night club before I sang in the Village. So when I sing, it's what I feel about the song, a spontaneous kind of thing."

Through the Bon Soir, the theatre actually did come to her. It was an off-Broadway revue, Another Evening with Harry Stoones, in which she sang a blues and comic number. She stopped the show on opening night, but that proved to he the closing night too. However, the Bon Soir engagement also led to an appearance at a midtown showcase, the Blue Angel, where she was seen by David Merrick who was preparing to produce the musical version of Jerome Weidman's early novel I Can Get It For You Wholesale. She was given a minor role in it and once again proved to be a show stopper with her single song, Miss Marmelstein. The response to her performance on stage and in the original cast recording of the show, as well as her work in an album of songs from Pins and Needles convinced Columbia Records that she was worth recording on her own. "When I first auditioned for Goddard Lieberson {Columbia's president}," Miss Streisand relates, "he said I wouldn't sell records, that I was much too special, that I would appeal only to a small clique who would dig me. But the first album went right on the charts, and the second one is on the charts too. Everyone was surprised. But I always knew it would happen this way. People were ready for me."

Her records have made her a sell-out night club and concert attraction in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago as well as New York. Last October she appeared at the Hollywood Bowl with Sammy Davis. Jr. (her fee was $2,500). In December, as the sole attraction, she filled the 5,000-seat Arie Crown Theatre in Chicago for two nights in a row (her fee: $8,000 for each night).

WHAT HAS ENABLED this relatively inexperienced girl, lacking theatrical background, with no training of any kind as a singer or entertainer, to capture such a large audience so quickly? Mike Berniker, who has produced all her records, has watched her with fascination for a year and a half. "She's directed by intuition," is his explanation. "She has a feeling of rightness. And her convictions are motivated by the best possible kind of taste buds. But she is guided intuitively in her choice of material and in her feeling for it."

Although she cannot read music, she instinctively asks for adjustments in arrangements that will give her more freedom, according to Berniker. "She has the imagination and the ability to anticipate what something will sound like before she hears it," he says. "And she's invariably right."

Right from the beginning she has had unusual control of the sound of her voice, an ability to hold a whole note and to get different sounds out of it. But now, Berniker feels, she is able to control that sound even more. "There used to be an edge to the top of her voice," he says, "But now that edge is gone. She's still pushing just as hard, but it's not as evident as it used to be. In her third album, her new one, there's a real serenity - at least, for Streisand it's serenity."

This is a change that is, at least partly, a reflection of the overnight change in Miss Streisand's life. Most of it took place in a single year - 1963. In March she married Elliott Gould, who had been the leading man in Wholesale. She moved from her $67.20-a-month railroad flat with bathtub-in-kitchen to a duplex penthouse overlooking Central Park where Lorenz Hart once lived. She is the star she dreamed of being when she left Brooklyn only four years ago. She can now turn what were once considered evidences of "kookiness" to her advantage. As she looked around the packed Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles last summer, she exclaimed, "So many people! If I'd known they were going to be on both sides of me, I'd have had my nose fixed."

"I'm not a rebel any more," she says now. "I'm not a crazy kid who has to be heard. That fight is over because I don't have to work so hard to get my point across. As I go along, I find the need to express is much less. I want less of an emotional thing now."

Appropriately, her new album is "less of an emotional thing." It is made up of old standard songs, such as My Melancholy Baby and It Had To Be You, which she has never sung before. Instead of deliberately striving to be different in her treatment of them, she approached them, she says, as pretty songs with their own sweetness.

But won't her audience, so recently attracted to her because she was different, miss the old Streisand?

She smiled mysteriously. "An audience sees what you want them to," she said, with the calm assurance of one who is accustomed to being right.

End.