Dance Magazine

December 1967

Dancer- Choreographer- Show Doctor Now Film Director Herb Ross Talks Shop

by Lydia Joel

[Barbra Archives note: Below is an excerpt from the above article on Herbert Ross which appeared in this issue of Dance Magazine ... ]

Ross's thoughtful awareness, his down-to-earth charm, and his ability to get successful results has zoomed his career into the heady realm of Hollywood multi-million dollar films. His next, currently before the camera, is Funny Girl, the Columbia Pictures version of the Broadway hit which stars Barbra Streisand. For Funny Girl Herbert Ross is listed both as "co-producer" and "director of musical numbers." The wording of that last phrase makes lots of difference. Being "director of musical numbers" has enabled Ross to become a member of the Film Directors Guild, and it clears the path for future action. As a matter of fact, he has already selected the property for his first film directing job. It will be Noah, a musical with book and music by Leslie Bricusse, and its star will be Anthony Newley. For the future there is also penciled in a return to Broadway to direct a musical by British playwright Terence Rattigan, in which Lynn Seymour will appear. Funny Girl's producer, Ray Stark, will again produce.

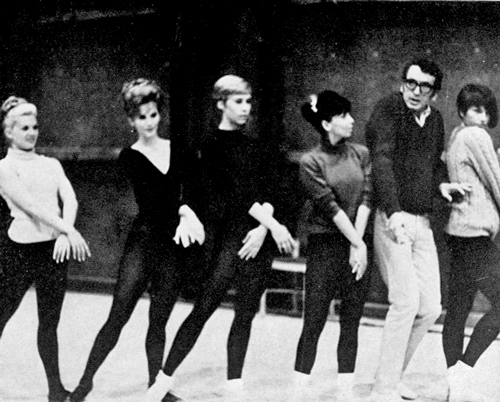

(Photo, left): On the Hollywood set of FUNNY GIRL Herb Ross indicates swan-like timidity to some of the corps

Right now, Herbert Ross is busy in Hollywood's filmland and, because he expects to be there for a considerable time to come, he and Nora Kaye have recently moved their household which includes three dogs and 15,000 pounds of books and antiques to a spacious home which they've bought in Beverly Hills, and which they are now happily remodeling for permanent living. It is not far from the newly purchased home of the Koreffs, Nora's father and mother, well known and beloved in the dance world. "California," says Nora Kaye Ross, "is a pleasure."

As co-producer of Funny Girl, one of Herb's jobs was the responsibility of arranging the production schedule. He was already mulling about that down in St. Lucia, hoping then to have Barbra Streisand for sixteen weeks of rehearsal prior to getting before the camera, "even though she knows the play backwards and forwards. But she just can't march to the footlights and sing a song the way she did on stage, no matter how brilliantly. In film an action has to be devised, the interpretation is different, there must be a staged conclusion that leads naturally into the next action."

As it turned out, he didn't get sixteen weeks with Barbra, but he did get twelve. "Not as much as I wanted, but much more than I'd ever get on Broadway.

"On Broadway there'd be four weeks of rehearsal and then a few more weeks of out-of-town tryouts. Some people find the pace of movie-making tedious, but to me those two weeks in Boston, Philadelphia, or New Haven are the longest two weeks in the world.

"Film-making suits me," says Ross. "With time to rehearse, time between takes, opportunities to shoot and re-shoot and, finally, time for cutting, dubbing, and editing, film is a great medium for a perfectionist like me."

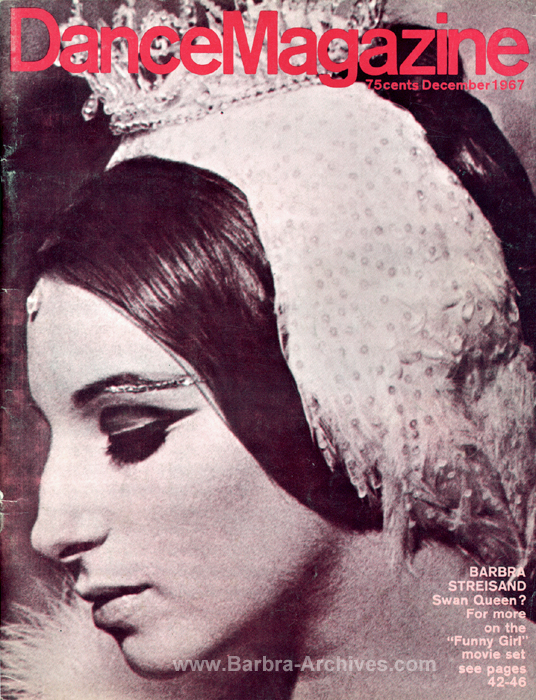

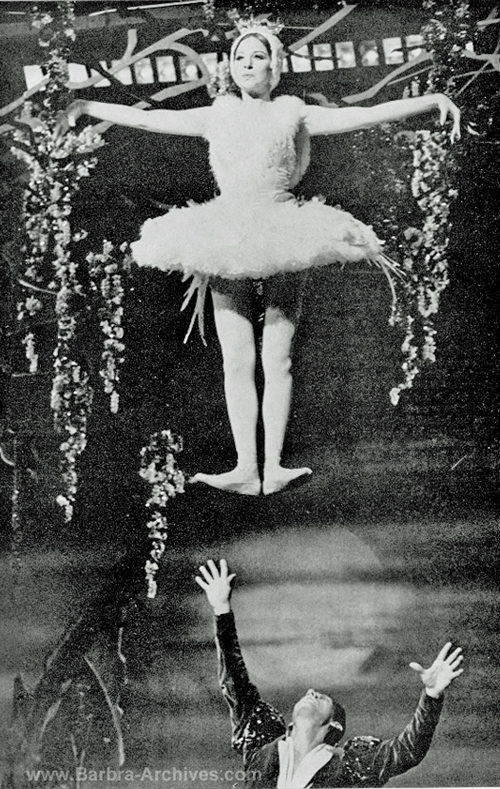

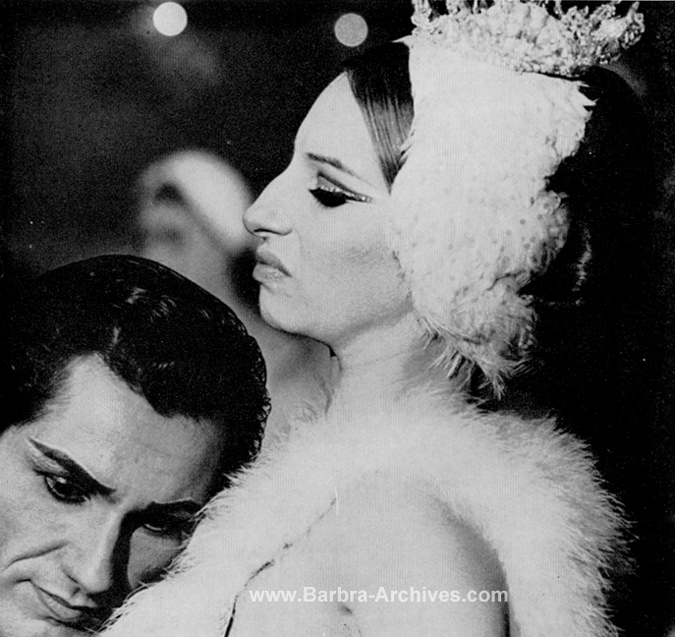

(Photo, right): Barbra Streisand, remote Swan Queen, eludes Prince Siegried (Tommy Rall)

At the age of 41, Herb Ross has had a background that permits him to know whereof he speaks.

Born in Brooklyn in 1926, he studied modern dance with Doris Humphrey, ballet with Helene Platova and Caird Leslie. At first he planned to be an actor and this lured him into a group which toured the South in Shakespearian repertoire. Returning to New York and to more dance training, he had no difficulty in soon finding work as a dancer. Before long he was in Olsen and Johnson's Laughing Room Only, Bloomer Girl, Beggar's Holiday, Look Ma I'm Dancing, and Inside U.S.A. Turning to choreography he scored a brilliant success with his choreographic debut, Caprichos, based on the etchings of Goya, which he created for Choreographer's Workshop in 1950. It was taken into American Ballet Theatre's repertoire almost immediately.

Ross was interested in the dramatic level, rather than the purely formal aspects of dance. "I was always attracted to themes that were actable. I liked plot in ballet and fundamental emotions like love and hate. I needed either an emotional drive or a story line that I could tell with the use of dancing."

Ross choreographed nine works in all for American Ballet Theatre. Most derived from literary sources, including The Maids (after Genet), Paean (after Sappho), Tristan (after Thomas Mann), and Metamorphosis (after Ovid). This list hints at his catholic literary taste. Said New York Times critic John Martin in September 1958, in reviewing the Ballet Theatre season, "Ross has given us three new ballets, all of them unviable - which should be enough to damn him. But for all their various offenses they don't succeed in obscuring the presence of an able, adventuresome, and genuinely creative mind . . . he's venturesome and iconoclastic."

(Photo, right): Miss Streisand, who cares abut the ballet, worked hard to do a parody that was funny, not foolish.

Ross has twice had ballet companies of his own. In 1950 the Ballet d'Action, which he co-directed with artist John Ward, appeared at Jacob's Pillow. In 1960 Ross formed the Ballet of Two Worlds which performed at the Spoleto Festival and toured Europe. Its star was Nora Kaye, to whom he had been married the previous year. The company had an all-Ross repertoire but had trouble getting off the ground economically.

The Rosses returned from Europe and there was a brief interlude when they attempted to live in a house on the Hudson, but being confirmed city people the role of country gentry proved unsuitable. Back in Manhattan Ross staged dances for a succession of shows including Take Me Along, House of Flowers, Tovarich, and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. And frequently he was called in as show doctor to assist directors in devising music and movement ideas, to coach dramatic actors, and to do what he calls "rescue work." Rosalind Russell, Martha Raye, Milton Berle, Dianne Carroll, and Angela Lansbury are among the many non-dance performers for whom he's done non-choreography.

Now on the set of Funny Girl he's finishing his part of the four-month shooting schedule. Almost all of it involves Barbra Streisand, who has had no formal dance training but who has, says Nora Kaye, "an instinctive feeling" for the dance. Says Ross, "Barbra's terrific. She's utterly willing to learn and she's a hard worker. While she was preparing for the parody of Swan Lake Barbra immersed herself in ballet lore, went regularly to the performances of the Royal Ballet when it was in Los Angeles, and proved thoroughly receptive to coaching."

Barbra had a ballet barre every day and, according to mentor Kaye, "She did so well that after the first rehearsal of the ballet scene she was spontaneously applauded by the other dancers (professionals) in the cast." Filming of the seven-minute Swan Lake sequence took a full week of working from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. "We tried having her on pointe, but that was too much," continues Nora Kaye, herself a Swan Queen of note. "Yet if it weren't for the fact that Barbra wears soft slippers you'd really think she was going to do Swan Lake." Helping to support this scene in reality is her exquisite costume, a near replica of Pavlova's for The Dying Swan.

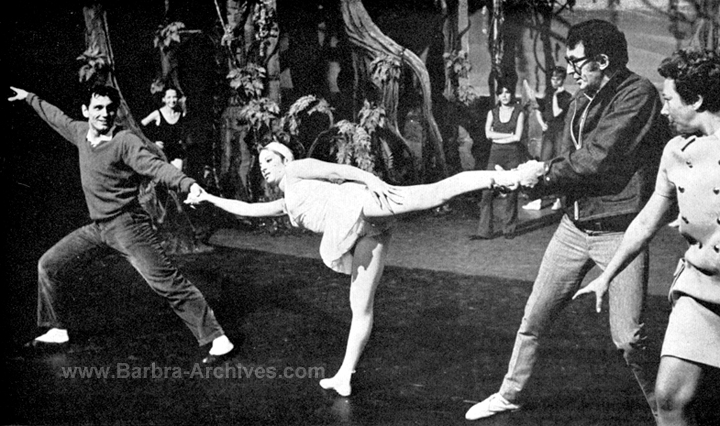

(Photo, above): Tommy Rall and Herb Ross, marking the role of Von Rothbart, each give a yank at the Swan Queen. Nora Kaye, at right, assists.

How did Swan Lake get into Funny Girl? "It's not at all outlandish," says Herb Ross. Fanny Brice was enormously interested in dance and had in her own repertoire a number of sketches satirizing ballet and modern dance, among them spoofs of Mary Wigman, Martha Graham, classical ballet, gypsy dancing, and, of course, the famous social protest dance of Rewolt. Fanny Brice's sketches were never vulgar lampoons. They were based on real knowledge of dance and the trick was to make Barbra Streisand reveal enough skill in what she was doing so that the comedy would be pointed satire and not foolishness. That worked. But because Streisand has a strong pull toward ballet. "There were even a couple of times," says Nora Kaye, "when I had to remind her that she wasn't doing a straight Swan Queen."

The film's distinguished and highly regarded director, William Wyler, is giving Ross considerable leeway on this film and this in itself is a vote of confidence on the part of the veteran toward the methods of the choreographer-director. In addition to the Swan Lake sequence, which lasts seven minutes on film, there are fifteen other sequences for which Ross is responsible, along with their lead-ins and lead-outs. Although she won't be listed in the credits, Nora Kaye is on the set a good deal of the time, as is Ross's assistant Howard Jeffries, who acts as dance-in sometimes and who, as dance captain, sets the group numbers. Says Ross, "Nora and I also keep our eyes on big groups all the time. You have to be able to hold the entire movement of twenty-five or thirty people. In a chorus I try to give each person an individual character and I keep at it so that they react personally and individually. It makes the scene alive. But I also care about where the action is. I usually have a floor plan, which could exist as an abstract design.

"There are many possible approaches to staging musicals for the theatre and for the movies. Some directors like to stress the differences between the spoken and the sung or danced sections. I belong to those who believe that the musical is moving in the direction of increased integration of theatrical elements and should continue to do so more and more.

"When musical comedy established itself on the American scene as a form separate from opera and operetta, it fell into conventions as rigid as Kabuki. For no special reason twenty-four girls might come out and dance in precision kicks, with no relation to the plot. It might have a dazzling effect because of size or spectacle, but it didn't make much sense. There's still a hangover from that tradition and I guess there's a place and a public for it, but there are a number of us who are knocking ourselves out trying to integrate mime, dance movement, acting, and singing so that one is never conscious of numbers going on and off. Our intention is to find a total theatre experience with all the elements integrated together so the audience is not conscious of going from one medium to another. But it takes a good deal of working out, even when one gets a chance to do it.

"I was sure, for instance, that the success of West Side Story would make a difference in the films that followed it. I hoped it would pave the way for many more imaginative musicals. I even expected that dancers would help change theatre and film. But the truth is that there are still only a handful of writers, producers, directors, and, especially, those important men who have the final okay, who are sufficiently aware and flexible to see how dance can be of help to them.

"In the meanwhile, young people must find a way to work out ideas and experiment. You don't learn from hits, you learn from flops. That's how you find out if you've aimed too high, or where you've failed. And that's why we need subsidy.

"I've never stopped being interested in dramatic ideas. There are certain plays of Shakespeare I'd like to try. But it's not easy for someone like me to take that step. It isn't very lucrative.

"Broadway musicals or Hollywood films deal in the immediate. Art is on another aesthetic level. The obligation of the artist is not to interest a mass public; it frequently takes many decades for the masses to catch up with the work of an artist."

(Photo, above): Tommy Rall rests his head on the bosom of inimitable Barbra, who sniffs in aristocratic disdain

But Herb Ross, with a foot in each world, seems to be working toward speeding time up as he helps bring the resources of serious dance onto the stages of the popular arts.

END.

Page credits: Copy of Dance 1967 supplied by Rafe Chase, from his collection.