Cosmopolitan Magazine

February 1968

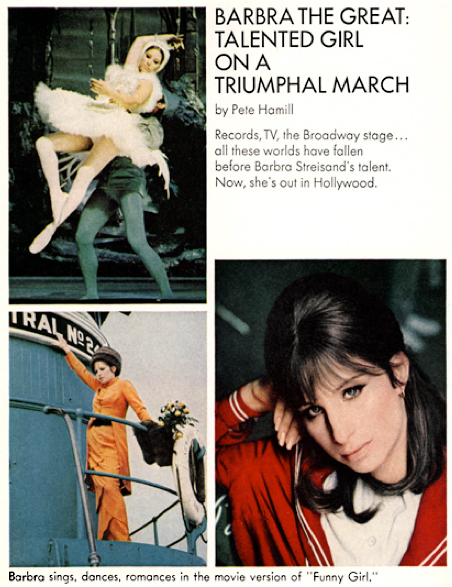

BARBRA THE GREAT: TALENTED GIRL ON A TRIUMPHAL MARCH

by Pete Hamill

Records, TV, the Broadway stage ... all these worlds have fallen before Barbra Streisand's talent. Now, she's out in Hollywood.

The movie at the front of the cabin was Our Man Flint, all about girls in purple bikinis saving the world from a mad scientist. I sat watching it at 35,000 feet, with a headset plugged into my skull, wondering vaguely about the smashing blonde beside me, and falling into a half doze. I dreamed of the Last Judgment: of great, turret-breasted women with lilac eyes and plaster-white teeth, rounding up the last surviving men in America. They had us in a vast grassy pen that somehow resembled the ball park of the Los Angeles Dodgers, and we stood there in the bright California sun, waiting for the final destruction. It was rumored that we were to be dropped over the edge of the Pacific Palisades, ten at a time, and in my dream the Amazons were all laughing while a high, pure voice soared out over an invisible loudspeaker. Suddenly I realized the voice belonged to Barbra Streisand.

"People, People who need people ..."

"Da you brug in the brindirig?" the blonde said.

"What?" I shouted, awake now.

"Do blue dirk in the birmarring?" she said again. She had brilliant blond hair and brown eyes and she was bursting out of her seat belt. I took off the headset.

"Do you work in the industry?" she said. Oh. She was not talking code. The industry was Hollywood: TV and movies and press agentry and talent selling. "No," I said. "I'm not part of the industry. I'm a reporter."

"Oh," she said. "I saw you reading all those clippings. I thought you must be in the industry."

Well, in a way, I would be writing about the industry, I explained. I was on my way to the Coast to write about Barbra Streisand.

"God," the smashing blonde said. "Isn't she beautiful? So exotic. And so .... talented."

And the girl started to tell me about her life. She was from Pennsylvania (not a deserted mining town, but almost), and she had started acting in high school and won a couple of beauty contests and then been married to a sergeant in the Air Force and then decided that she didn't want that kind of life ("tough steaks and puking children") and decided to go into show business. A year before she had gone west and was given a screen test and signed with an agent ("he's a bastard") and obtained a divorce and had been in two TV series so far ("small things, really, but you need the credits to get anywhere in the industry"), and was studying at a dramatics school in West Hollywood. Somewhere over Idaho, she asked me if I knew Barbra Streisand well.

"Just slightly," I said. It was true.

FOUR years before, I had followed Barbra abound for a few days, writing about her for the first time. She was a charming, funny girl then with a zany stream of talk, a fine tough Brooklyn sense of the absurd, and, of course, the hard core of that beautiful talent. Everyone then talked about how her future was unlimited. She couldn't miss. And she didn't. In four years she had done everything a show-business talent could do, and a little more. She had made the covers of Time and Vogue. She had carried an entire Broadway show (Funny Girl), her record albums were big sellers. She had done two highly praised TV specials. She had given an outdoor concert in Central Park in New York, which brought out 130,000 people to hear her, while another 30,000 milled about on the edge of the park. She had married and, so far, it had lasted (although, in early December her husband, actor Elliott Gould, was bitterly complaining about Barbra's "dates" with Omar Sharif), and I when she gave birth to a son, the New York Daily News threw all the affairs of the earth off the front page and went with a headline that said "MILLION DOLLAR BABY!"

Now, she had come to Hollywood to make a $10,000,000 film out of her show, Funny Girl, a musical about Fanny Brice, and people in New York were wondering who would make the inevitable movie about Barbra Streisand.

"Tell me," the blonde said, "what's Barbra Streisand really like?"

I laughed out loud. The blonde was puzzled. "Sorry," I said. "I was just thinking of something." The blonde started reading Variety furiously. I slid low in the seat, stretching my legs. What is Barbra Streisand really like? What, indeed, is Claudia Cardinale really like, or John Wayne, or Brigitte Bardot? What, after all, is Lyndon Johnson really like? It was a joke: If we had learned anything, in growing up, it was that we knew nothing about anyone and pretended that we did. I stretched again, my legs cramped from the journey. Then I heard something tear. The seat had gone out of my trousers. A long, deep slash, beyond emergency repair. I started laughing again. In the movies, Cary Grant would be the reporter and would take the blonde away with him for champagne and dancing and breakfast in bed. In real life, you sat with your pants split and your drawers showing, laughing blackly, wondering whether you would walk through the terminal with the typewriter or the briefcase behind you.

"Good luck with your story," the blonde said, as we waited in the crowded aisle after landing. "Thanks," I said. "Good luck to you." She was looking at me as if I were really Richard Speck.

I WAS met by a girl named Carol Shapiro, from the Columbia Pictures publicity office. Yes. Barbra was fantastic. She had such talent. She was marvelous so far in Funny Girl. It was too bad I hadn't been on the set a few days before when she had done a ballet.

"I studied dancing," Miss Shapiro said, "and all I can say is that Barbra must have studied dancing, too, at some point. Nobody could have that kind of grace and poise without studying somewhere along the line."

"Maybe it's just California," I said. "Maybe it's just that out here you can do anything."

"No," Miss Shapiro said. "It's talent."

I checked into the Beverly Hills Hotel, one of the great hotels in this country. Miss Shapiro telephoned Jack Brodsky, the unit publicity man, who said he would send a car for me in the morning. She gave me a handful of press releases and we said good night. In my room, I sent the trousers to the valet for repair, and then called friend, Budd Schulberg [author of What Makes Sammy Run? and The Disenchanted] He lives in Beverly Hills, not far from the hotel. I went up to see him, in a cab. He was in his second year as director of a writing workshop in the strange, bleak, Negro ghetto of Watts. His son was in Vietnam.

That night, we drank whiskey and talked until almost five o'clock in the morning.

MISS SHAPIRO and I drove out to the studio at 10:15. Usually, the day in the industry starts at 8 A.M., and sometimes earlier. William Wyler, the director of Funny Girl, had worked out a different schedule. He preferred European hours—a day that started at 11 A.M. and went to about 7 P.M.—because his stars could then have some social life in the evenings, and still be fresh and relaxed in the morning.

We parked in the anonymous black-topped Columbia Pictures parking lot, where the rank and file keep their cars, and walked to the main entrance. Funny Girl was shooting in Studio 16. It was about three city blocks away from the entrance, and the life of the movie lot seemed busy and full. A large Negro sold cigarettes and cigars and Cokes from a stand; carpenters and stagehands hammered and sawed in a workshop. In front of Studio 16, four horses munched on a pile of hay—living props for a Gregory Peck Western being shot around the corner. In the Studio 16 private parking lot, there were cars in the space reserved for Ray Stark, producer of Funny Girl, and William Wyler, the director. Barbra Streisand's space was still empty. The door was locked on the trailer that served as her dressing room, and the golf cart used for transporting her around the lot was parked out front.

Inside Studio 16, the vast resources of the Hollywood technicians had assembled a detailed replica of an 1890s Coney Island dance hall and beer garden: a huge proscenium and an orchestra pit with a runway wrapped around it, two tiers of balconies at left and right, old electric fans hanging from the ceilings, the whole place decorated with gold scrollwork, paintings of Greek maids and sylvan gardens, all art nouveau and innocence, like the 1890s themselves.

"Where's Barbra?" I asked.

"Oh, she'll be along soon." Miss Shapiro said. "You should have a good day. They're doing the dance on roller skates today."

WHILE carpenters hammered, electricians fiddled with lights, and men complaining of hangovers gulped paper cup after paper cup of cold water from the cooler, I read the movie script. Funny Girl is all about a fictional character named Fanny Brice. There was a real Fanny Brice, of course, but hardly any of the people who go to movies these days can remember her, and those who do, think of her as Baby Snooks, a radio character of the thirties and forties.

In the script, she is a homely girl who makes good through art. The saga goes like this: Fanny tries out for a show in this Coney Island dance hall. She is So Bad. She's Funny. The audience gives her a Standing Ovation. The people who run the dance hall have no foresight. They don't know what they Have. They Throw Her Out. She sings a lament. The World Is a Desolate Place. But wait. Ziggy was Out Front. The great Ziegfeld who was Out Front in every show biz saga in the history of man. He was Out Front for Jolson. He was Out Front for the Dolly Sisters. He was even Out Front for John Payne. Now, he is Out Front for Fanny Brice. He comes back, signs her for the Follies, and overnight, Fanny is A Star. But wait. Into every show-biz life Some Rain Must Fall. In Fanny Brice's life, the Rain is Nicky Arnstein. Nicky is the blight of her life, her only real tragedy. He is a gambler. They have a romance, they marry. He Treats Her Badly. She Walks Out. He Wants Her Back. She Won't Take Him. She must live with this personal tragedy. She is Laughing On the Outside, Crying on the Inside. Fade-out.

Ah, well. Funny Girl worked on Broadway. Maybe the movie would work. Columbia and Ray Stark were betting $10,000,000 that it would and, besides, since The Sound of Music, musicals were respectable again; they had been Out for a long time: now the Sound of Money had brought them back. I was finishing the script when Barbra Streisand arrived.

She was dressed in a maroon jumper with a sailor neck. baggy, black, little-girl knickers, black high-button shoes, and she was talking to Ray Stark. Stark is a friendly, medium-sized man with red hair, a face pink from the sun, who worries a lot about his weight, and is, in many ways, the antithesis of a conventional Hollywood producer. I never heard him call anyone baby, he respects experimental film makers, and he can entertain you with good talk about painters, writers, or sculptors while carrying the grosses of his pictures in his head. He was also Fanny Brice's son-in-law and the original Broadway show and now the movie were his idea. Streisand seemed taller than he was (because of the heels), and they talked intensely for a few minutes. Stark saw me, remembered me from a brief meeting in Montego Bay a few years before, said hello.

Barbra said, "How are you?" .... "Hiya." . . ."You wrote one of the first pieces about me, didn't you?"'. . . "Yeah, four years ago." We agreed that a lot had happened since. While she talked the extras looked at her; Fox, the cop at the door, smiled in her direction; the stagehands nodded her way. A woman in a blue smock was standing behind her, studying the costume. She suddenly noticed a small scuff on the heel of Barbra's right shoe. She moved off swiftly. Stark took Barbra on the side for a brief talk. The woman in the blue smock came back with an aerosol can in her hand and without saying a word, knelt down and sprayed Barbra's black shoe.

"Goddammit," the woman said, looking at the can. "It's brown!"

Barbra looked down and shrugged, said goodbye to Stark, and started toward the stage. "How has it been so far, making your first film?" She smiled. The gray eyes lit up.

"It's—well, half fun and half—you know."

She made a trembling gesture with her hands.

ALL movie sound stages have their own peculiar life and their own peculiar sense-of time. Strangers are thrown, together for weeks, months, hours; their money, talent, time, drives, egos, ambitions, failures, and fears are mobilized toward this one thing: the production and completion of a motion picture. The visiting journalist can seldom arrive at much truth; he is a voyeur, entering this strange world for a while and returning with fragments. He comes home and writes his piece, and stands in a favorite saloon with friends, and someone asks, "What's she really like?"

"I don't know," you say. And nobody believes you. So you recite the fragments because they are your only evidence. In Hollywood, in the days I was there, I didn't talk much to Barbra Streisand. In the four years since I first wrote about her she had become a star. Not one of your ordinary, run-of-the-mill Donna Reed-Deborah Kerr-Peggy Lee-Sandra Dee stars. But a Superstar. I hadn't seen it happen;. I was away a lot during those years. In other countries, and on the road. I had seen one of the TV specials, a rather campy creation that had Barbra Streisand as a little girl, playing in a department store at night, or something. It seemed pretentious and plummy, with a cloying, self-conscious air to it. It was the sort of faggy, aren't-we-cute thing that was very big in New York that season. But through it all there was Barbra's wonderful voice—eclectic in its ethnic range, yes, but full and rich, shimmering with drama and controlled passion. That voice was no mere mechanical instrument; it was a dramatic weapon, and she used it to its limits, and a step beyond. There was, to be sure, something arch about the choice of songs: They were those special little songs that vanish from the mind the morning after you have seen the show, and enter the repertoire of piano players in intimate saloons. Yet, even, these became something as Barbra polished and burnished them with that voice.

In Hollywood, there was another influence at work. Barbra Streisand had become such a big star, had gone through such a flawless four years, that she had already entered into the peculiar isolation of fame. Miss Shapiro and Jack Brodsky, the publicity people, tried to get her to sit down with me to talk, but Barbra was busy with work, or studying the script, or having her baby over at lunchtime, or talking to Wyler.

It didn't matter to me and, of course, it didn't matter to her. And yet there was something oddly pathetic about it all: When Barbra Streisand wanted to sit down, someone was there with the chair. When she sat down, makeup people surrounded her, patting the, dampness of her face, straightening a loose hair, checking the shoes, handing her a script— Yes, Miss Streisand ... No, Miss Streisand ... Of course, Miss Streisand. The terrible thing to me was that she had grown used to it. She was Barbra Streisand the Superstar now, and she didn't need anybody. She could be rude to people if she chose to (and she was, possibly unconsciously), and she could be pleasant. It didn't matter.

WHAT did matter was keeping her winning streak going. So far, she had done everything right. Now, it was apparent she felt the film version of Funny Girl had to be her greatest triumph.

So she would go through a scene over and over until it was precisely right. Wyler had never directed a musical before, and was sharing the direction of the film with a tall, lean man named Herb Ross. Ross was directing all the musical scenes, with Wyler looking on.

I watched Barbra go through take after take of some scenes. Occasionally, Ross would finish, say the scene was fine, please print it, and want to move on, and then Barbra would have an idea, some minor alteration, and they would go through it again and she would be right and the scene would be marvelous. Other times, she was just moving a simple scene into a more baroque version, adding scrollwork and curlicues as tormented as the art work on the pasteboard walls of the reconstructed dance hall. Producer Ray Stark would look in once in a while, knowing the production was behind schedule, hoping it would catch up. No, he told me, there had never been any question that anyone but Barbra would play the lead in the Funny Girl film version.

"Barbra is good," Stark said. "With Willie Wyler, she's great. When she was a success in the play, there was no question about who would do the movie. I just felt she was too much a part of Fanny, and Fanny was too much a part of Barbra to have it go to someone else. Sure, there's always an element of risk when you take someone who has never made a film and put her in a $10,000,000 production. But this is Barbra Streisand: Plus Willie Wyler. Plus Herb Ross. Willie Wyler has had thirteen Academy Award nominations. He has won three Academy Awards." Wyler, a small white-haired man who smokes long filter-tip cigarettes and has a kind face, said: "Barbra can do anything. We haven't asked her to do anything that she can't do. And she does it half a dozen different ways and that makes my job easier. She's not the most relaxed person, but neither am I. She worries about everything. I think that's fine. Lots of people don't worry about anything, but I'd rather have her worry too much than too little."

WATCHING Barbra work, you can see how the Funny Girl film might become something really first class. One afternoon, I was reading the call sheet. There were 138 extras sitting in the audience in bowler hats and moustaches and bustles; 12 musicians in the pit; 10 show girls from the chorus line, dancing marvelously on roller skates; 4 assistant directors; 18 lamp operators; 11 hairdressers; 15 costumers; 9 men working on the cameras; 7 prop men: 8 grips [scene shifters]; 2 still photographers; and 1 cop, standing at the door. Barbra was sitting in her canvas chair between takes, talking in her scattering, rapid voice.

"It was never true that I had no discipline," she was saying. "It's just that I never played to the balcony. I always played to the best seat in the theater. I always played to my own reality." Fanny Brice was important to her. "She was very much like myself," Barbra said. Then Stark arrived and she left with him, breaking off our talk without a word.

Soon, she was up on the stage, playing a clumsy, knock-kneed young girl, moving with a peculiar kind of awkward grace. In the script, this was the moment after Fanny's fiasco in the dance hall. Now, Barbra was singing to the audience, alone on the stage. The song was "Am I Blue?" [note: "I'd Rather Be Blue"] The young girl was tentative at first, not sure of a reception, but then the audience was with her, the music building, the voice subtly moving from hesitation to full confidence and then rolling into a rousing finale. It was an exacting and artful performance, and even the grips and stagehands—the most hardened men in Hollywood—broke into applause. For the first time I understood what she was doing with this very ordinary script. She was treating it the way a great performer treats an old standard. She was looking deeply into it, past the glib surface, and locating , the emotion that was there at the start, before repetition and second-rate artists had corrupted it.

She did almost a dozen takes of the a scene, and each time it came out fresh. The hired audience of extras was dazzled. So was I. At the end of the day, after the dance number, Barbra took off her roller skates and walked across the sound stage in slippers.

"I was trying to decide how to describe my life to you," she said. "All these people patting you, and talking to you, and working you over. It's like being a fighter. A fighter between rounds." She went into the trailer, while the extras lined up at the telephone down the studio street to call the casting offices about other jobs.

A NUMBER of people I talked to that week said that Barbra Streisand was a peculiar sort of girl to be in Hollywood as a Superstar, in her first film. There was, first of all, the matter of her looks. You could feel something in all those hordes of extras that was the spirit of malice and resentment. There were a lot of women in their forties, who once had traveled west like the blonde on the plane. They had had the teeth capped and the nose fixed but, somehow, nothing had happened. They had blamed it on agents, or luck, or not sleeping with the right people, and one morning the creamy flesh was wrinkling and they knew that none of it would happen, and they were working on the Strip or as extras in other people's movies. They would never really understand Barbra Streisand. Her sculptured, Semitic nose: everybody has written about it and talked about it. But instead of hurting her, Barbra Streisand's nose was now part of her beauty, turning her into an exotic. The looks and the voice made her an original. Both of those plus the work.

One morning I dropped by her rented house in Beverly Hills. There were three automobiles in the driveway and a small dog named "Sadie" running around the house, and a lawn sprinkler turning lazily outside. I had coffee. Barbra came down with her husband, a good-looking young man named Elliott Gould, who was dressed in corduroys and had his hair grown long for a part in a film called The Night They Raided Minsky's. Barbra was late. She said goodbye to Gould and we dashed to the car. She slid behind the wheel, turned around, and was about to leave when her hairdresser, a middle-aged Negro named Grace Davidson, rushed out, followed by the dog. She got into the backseat of the car with the dog. Barbra talked all the way as we drove through the seedy center of Hollywood.

"A performer has a given task," she said. "It's part of the job to do it right. You don't ask the motivation. You just do it ... I'm very tight with my time. It's a tough fight to get me to do interviews. I have too much to do and think about. If you talk or verbalize too much about your inner feelings, then your feelings don't mean the same thing they once did. Then reporters get your meaning wrong, anyway. It's very frustrating.

"Almost since the beginning, all the publicity has been frustrating. The stories are always so stupid. There's one going around now that, because the new photographs of me look good, I must have had my nose done. They can't just say that I look good and forget about it. That's one reason why I couldn't care less about publicity."

Did she ever stop working? Was there anything done for enjoyment, when she was not thinking about her work and the film and what she would do the next day?

"No, never," she said, driving easily, enjoying the feel of the huge car, a Chrysler Imperial, as it moved through the hot streets. "I guess that's hard on the people who live with me. But I can't ..."

THERE were other things happening in the world—she realized that; yet these things were often too depressing to think about. "Our foreign policy is very —unreal. I guess they think they are sticking to the American tradition or something. But all that waste and killing. Maybe we just will have to learn to lose some face. I mean, this is the destruction of the earth we're risking. In a way, it's probably all inevitable. The, thing is that, so far, any scientific development exceeds our emotional development. Our leaders sometimes seem very childish. They don't seem to realize that we can destroy ourselves."

She was quiet for a moment. "That's one reason why I decided I was not going to waste my time on trivia," she said. "Life is too short and precarious. The hippies are going the other way. They're looking for some kind of instant Nirvana on drugs. But you can never give up fighting. That's the thing. I feel I've got to take advantage of my time. Life is too important to put up with a lot of silly things."

The solution was work. Barbra said working with Ross and Wyler on a movie was one of the important things.

"We can disagree on a point of interpretation," she said. "But money is being spent: you've got to do something, you've got to produce. There's no time for self-indulgence."

Movies, she said, were "a different kind of discipline from the theater. All those bright lights, close to the retina, lots of people standing around . . . you can't fake anything. That camera sees too clearly." She wondered about success, and what had happened to her, and all the people out there in the audience who didn't know anything about her at all, except that she was an entertainer.

"If I had something to say to them," she said, "I would say, 'Don't envy.' Everybody in their own way has problems. They should try to make their own lives the fullest they can be."

THROUGHOUT her monologue, she was cool, almost cold. She had a day's work ahead of her. I asked her how she liked Hollywood and Los Angeles in general.

"Well, it doesn't matter where you live," Barbra said. "It's how you live, what you live, who you live with. And the rest is extra. Like the weather. This is a small town, really, in its attitudes. It has its status symbols, and it's small, narrow life. But I'm not involved in any of that. I just appreciate the weather and the driving. But the place doesn't really matter."

We were at the studio, and the gate was rising while the guard waved us in. Extras were moving toward Stage 16. Barbra Streisand got out and said goodbye and went off to see rushes. That was it. The girl from Brooklyn with the odd-looking face and the big talent was a star now, and there was nothing really to find out about her. I went to the press office to arrange for a ride to the hotel, where I could check out and get a plane back to New York. At the cigarette stand, I met one of the Funny Girl extras, a heavyset woman with washed-out orange hair. She was seventy-eight years old and said she was once married to Fatty Arbuckle, the comedian of the silent era whose career was destroyed in a lurid sex scandal.

"Are you having fun?" she said.

"Sort of," I said.

"Barbra is a real star, isn't she?" she said, and her voice was sad and wistful with the knowledge of too many years spent in the industry, looking for jobs and seeing all the bright young people arrive and blaze finely and vanish again. "She has a lot of talent."

"Yes, she does," I said.

AT the airport, I picked up a paper. The front page was about a fierce battle in Vietnam, away out there in the real world, where real young men spilled real blood and fired real guns. There was an item in a gossip column saying that Barbra Streisand was being "difficult" on the set of Funny Girl and the production was far behind schedule. I didn't really care. All the way back to New York I slept without dreaming. And, coming into the city, I thought about a young Negro soldier I had seen in Vietnam one afternoon in a place called Bong Son. One moment he was standing beside me. The next moment, he was dead with a bullet slammed into his chest. I never found out if he had any talent.

END

Related: Funny Girl Movie

Page credits: Article provided by Mark Iskowitz, from his collection.

[ top of page ]