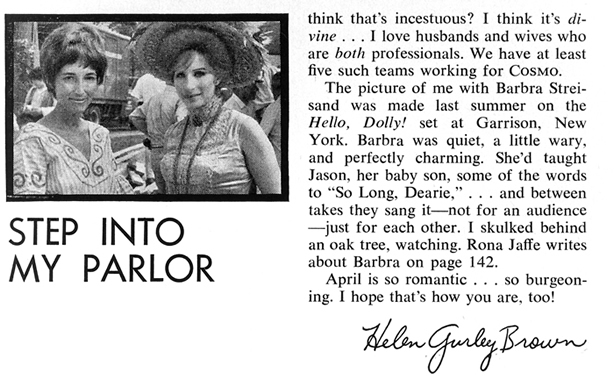

Cosmopolitan: April 1969

BARBRA STREISAND: “SADIE, SADIE, MARRIED LADY...”

THIS MAY BE THE FIRST ARTICLE TO CAPTURE BARBRA AS SHE IS

BY RONA JAFFE

I first met Barbra Streisand at a party, before she had opened in I Can Get It for You Wholesale, or had appeared at the Bon Soir, cut a record, or been married. Very few people had ever heard of her. Our host said to me: "Go talk to Barbra Streisand over there; she doesn't know anybody." She was standing in the corner — a skinny teen-ager with a Modigliani face, wispy hair, and a funny peasant dress. She was with Elliott Gould and they were holding hands, watching the festivities they were no part of, like two scared kids. She was so shy that making conversation with her was like getting blood out of a matzo, but I could see from her face that she was grateful someone had made the effort.

A few minutes later, a girl who identified herself as a press agent of Barbra's came up to me, giggling, and said: "Barbra Streisand thinks she's flat-chested so she's got the front of her dress stuffed with tissue paper—you can hear it crackling. Go look." I didn't. I thought, what a mess it was to be just starting out in show biz and have to put up with people who said things like that to make one sound interesting.

When Barbra first appeared in a night club—the Bon Soir in Greenwich Village—I went down to see her. She was sharing the bill with a female impersonator named Mr. Lynne Carter, and the place was only half-full. I got a table at ringside and sat through two shows, mesmerized by that marvelous voice, the impassioned face, the expressive hands with the long fingers and Dragon Lady nails. I had no doubt then that Barbra Streisand was going to be a big star.

OCTOBER 1968: I drove up to Barbra Streisand's rented house, in Beverly Hills, which she had leased for three or four months to make her third film, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. (Hello, Dolly! is now in the can.) It was a superstar mansion, the kind you see in the movies, hidden from the road by a long driveway and spacious grounds. I was relieved to see that none of the cars in the driveway looked very imposing; there wasn't a Bentley or a Rolls in sight. The rent on the house must have been high: The landlord let Barbra build a tall, ornate, white wooden fence around the swimming pool so the baby wouldn't fall in. There were rooms upon rooms, housing Barbra, husband Elliott Gould (this was before they had separated), their twenty-two-month-old son, Jason, a baby nurse, a fulltime secretary, a dresser, a Chinese chef—and Sadie, a fat, fluffy white poodle. I was with Barbra's publicist, David Horowitz, a nice, haymish man — the kind of unusual press agent you ask to stay for the interview.

The house was exquisitely furnished by its owner, film director George Axelrod, with antiques, some kooky things, and original paintings by famous modern artists, and there were lots of windows overlooking the gardens. While I was waiting for Barbra to come downstairs, I went into the huge kitchen, where her Chinese chef, Felix, was making homemade eggrolls, the hors d'oeuvres for an entire home- made Chinese dinner. He gave me one to sample, and it was as different from "takeout" as Maxim's is from Horn & Hardart. Being one myself, I knew then that the Jewish kid from Brooklyn had indeed found success and happiness: homemade Chinese food whenever she wanted it instead of waiting until Sunday night to go to Flatbush Avenue to "eat Chinks."

"We have company for dinner," Felix said.

"How many people?"

"A lot." He smiled. "Four."

As I sat in the living room. drinking beer and waiting for Barbra Streisand, I thought about all the things I already knew about her. People who didn't know her but who had read her interviews said she had changed. They said she was an imperious, rude monster. People who knew her well said she hadn't changed. She was still shy. Hardworking. Professional. Adamant about things that mattered. Right about them. It took her a long time to make a new friend. She had to trust the person first. She was wary of the new people who flocked around her now just because she was a star, when nobody had wanted to bother with her before. Her best friends were still her oldest friends: Sis Korman, occupation housewife, who comes to visit her often and stays long; her manager, Marty Erlichman (Barbra had once said: "Other people love money, but Marty loves me"). I remembered I had met Barbra one time backstage during the intermission of Funny Girl, on Broadway, and she had talked to me about literature, because I suppose that's what most people think they should talk to authors about, and she had said she liked Dostoevsky and Chekhov. And she'd said that she never had time to read a whole book any more and it made her feel guilty to have all those books piled up in her bedroom at home and be unable to finish them. And, I thought, how many people would just have said: "I read your book and loved it," when they hadn't read it at all.

Now, in Beverly Hills, she came into the living room and we shook hands, which is a dumb thing for two girls to do but is the kind of thing you feel like doing when you meet Barbra. "I'm glad you're late," she said, "because I'm late."

Her hair was long and straight, parted in the middle, blondish brown, and she was wearing the new look in make-up: very little, subtly applied. Her face is softer than it appears in photographs, and quite gentle. She was wearing a navy-blue long-sleeved shirt, matching wide-legged slacks, a beige sleeveless Bonnie Parker sweater, some antique chains around her neck, and bone-colored high-button shoes.

Barbra went to the bar to get a Tab because she's on a diet. "Last night I was dying for some crappy won-ton soup," she said. "Not good won-ton soup [evidently the kind Felix makes], and not really crappy won-ton soup, but medium crappy, the kind we used to get in Brooklyn, where the kreplach are chewy, not mushy. I can't find it in Los Angeles."

She sat down and lit a cigarette. "I have to lose eight pounds and I just can't. I'm O.K. in the morning; I have my skim-milk milkshake with the diet coffee syrup, eighty calories, and then I do exercises and swim in the pool, and then I'm so crazy I just go and eat a whole container of Wil Wright's coffee ice cream — two hundred calories for half a scoop!"

"You ought to get Skinny Shakes," I said. "Eighty-eight calories for a whole pint and they taste like frozen custard." (That was before the Skinny Shake miniscandal broke, and the calories had to be recounted.)

"I read about them in New York, but they never heard of them here." Barbra sat up straight, her eyes wide-open in mock tragedy. "I'm longing for a Skinny Shake. I am longing for a Skinny Shake. Do you think they would ship them here in dry ice? No, that would be too much trouble."

"Oh, no, you'll get them," Horowitz, her press agent, said. "I'll call tomorrow."

I complimented Barbra on her shoes and she said, "I got them in Paris. They're last year's, see the pointy toes? They wanted me to go to Paris to pick out the clothes for On a Clear Day, but I just couldn't shlep over there and take the baby. So I'm going to have the costumes made; Scaasi for the modern ones and Cecil Beaton for the old ones. I think it's crazy the way they spend so much on clothes for movies when you can just buy them in boutiques." She jumped up to write something down on a piece of paper and sat down again.

"Those shoes look as if they ought to have roller skates attached to them," I said. "Where did you learn to skate so well for Funny Girl?"

"In the Brooklyn gutters." Barbra grinned. "But that's the extent of it, I can't skate any better than that. I used to go to the Roller Dome, you know, inside, where you rented skates, and my dream was always to have a pair of my own . . ." The grin turned wistful and she shrugged. "But I never got them. I wanted the good kind, with shoes, not the kind you clamp on that tear the sole right off your shoe like that."

I remembered my own Brooklyn childhood, where you always wore a skate key on a string around your neck as a mark of status and roller-skated to the penny-candy store on the corner instead of walking, even though it was half a block away. For years I had scabs on my knees, also a mark of status in those days.

"On top of everything, Howard Koch [her On a Clear Day producer] just sent me seventeen different flavors of ice cream from Baskin-Robbins," Barbra said. "Did you ever have licorice ice cream? Peanut-butter-and-jelly ice cream? Later, you can taste it. I sent him a note." She looked at her watch. "The baby should be up soon and you can see him. He's so smart—twenty-two months old and he knows all the letters, and he knows all the words to my songs, and he can chew gum! Did you ever hear of a kid twenty-two months old knowing how to chew gum and not swallowing it?

"He saw me chewing it and he said 'gum,' so I took it out of my mouth, and after he chewed it a while I told him to give it back, and he did. Now he chews it all the time. It looks so strange. I let him come on the set once when we were filming Hello, Dolly!—the scene with a lot of kids dancing with umbrellas, where they're doing 'Put On Your Sunday Clothes.' Now, whenever he hears any music, he wants to dance, and he says 'umbrella.' He thinks you need an umbrella when you dance because he saw that number. I don't like to take him to the set, though. He came one other time, when we were doing the 'Hello, Dolly!' number; there was me, his mother, in a red wig and a gold dress, with a strange man on each side of her, and he got upset. He didn't like it. I got embarrassed with him watching me. It was like having my mother watch me—I can't let her see me perform, either—because she knows I'm just pretending and it's not really me at all. Ooh, what is that—dust?"

She jumped up and began to dust a leather chair with her hand, then she went to the french doors and began to run her finger over the frame, looking for more dust.

"You're a real balabosta," I said. [That's somebody who goes around cleaning after the maid.] "I clean before the maid."

She grinned. "So she shouldn't think you run a messy house?" Barbra sat down again. "Well, don't you want to ask me any questions?"

"No," I said. "I just sit around with the person."

"Don't you take notes?"

"No. I just remember it all."

"Yeah? Well, I have a pretty good memory, too, and I remember most everything I say, and some of these interviews I read that are supposed to be about me—I never said those things. I don't know why, you come out here and all of a sudden they hate you. Those reporters have a ... uh ... journalistic concept, and they just write what they wanted to write before they met me. They write about me as if I'm some kind of a ... uh ... old-fashioned star, with an entourage. I don't have an entourage. I hate having people around me. I hate people fussing over me."

She picked at a broken nail. "I have a terrible memory when it comes to personal things, but I always remember everything that concerns my work. I can remember something somebody said about one of my songs four years ago. But at home I have to keep lists all over the house, and every morning I go around gathering up all the lists and then I still forget something, because I forget where I put the lists. You noticed when I jumped up just before to write something down?" She showed me the piece of paper. It said: CLUB SODA.

"The thing about my interviews," she went on, with a rather wry, resigned melancholy, "is that none of them are really me. They're not what I'm really like. I have this friend, Ernest Lehman, who produced and wrote the screenplay for Dolly! and a lot of other things, and who's a very nice man, and he said to me: 'Barbra, if they knew what you're really like, they wouldn't write about you.' Because I'm nice. I really am, I'm nice. But if they knew that, they wouldn't write about me."

The phone rang. It was Elliott, calling from the set where he'd just started work on a new picture. "It's called Ted, Alice, Carol, and Bob," Barbra said. "That's not the right order, but I always put Ted first because Elliott's playing Ted."

"I heard you were doing a new record album," I said.

"Well. I'm supposed to be, but I've only recorded three songs. I'm lazy."

"Are you a Taurus?"

"Yeah! How did you know?"

"Lazy and musical. Strong, a lot of drive."

"Yeah?" Barbra pondered that a moment. "Well, all right. What are you?"

"Gemini."

"What's Gemini?"

"Flighty and fascinating," I said.

"I like Virgo men," Barbra said. "I know three Virgo men. Elliott's a Virgo. What's Virgo?" "Selfless and analytical. Critical."

"I love them. Somebody did my chart once but I don't remember it. Do you want to see the baby? Then you can taste the ice cream."

We went upstairs to the nursery, a series of rooms down the hall from the master-bedroom suite. The baby was running around. He has huge eyes and blond ringlets, and it's hard to tell at his age which of his parents he most resembles; he looks like both of them. He ran over to his phonograph to put on a record of one of Barbra's songs. The song, from the as-yet-unreleased soundtrack of Hello, Dolly!, went something like: "I'm a woman who always gets my way.. ."

"Oh, do you want to hear that again?" Barbra said, obviously wishing he'd play something else.

"That," he said firmly.

Barbra started to play a picture-puzzle game with twenty- two-month-old Jason, a game where you had to fit a cutout of an animal into a space and then find and put the name of the animal under the picture. He got every one right.

"I'm not sure I could do that," I remarked. "I had an I.Q. test a few years ago and I put the elephant's tail where his trunk should be."

"You'll never get into college," Barbra said, grinning. Then she asked Jason to find all the letters and put them into a box as she called them off, and he did that one unerringly, too. "I hate to sort of show him off," she whispered, "but you can't help it, you're so proud of them. When I was pregnant, I found some beautiful antique letters made of ivory, in New York, and I bought them for him. so that's how he learned, because he played with them." (I noticed that most of the time we'd been together she spoke without accent, reserving that comedic Brooklyn dialect that is her trademark for her few moments of humor and for public appearances. Does a car salesman sell cars at home?)

Taking the baby along, Barbra showed me around the rest of the upstairs. She has a room to make up in—there was a phonograph there, and the baby put a record on right away. He seems to thrive on music, and when it's playing he can't stand still. Although Barbra had dressed and made up just before she met me, I noticed that everything was put away on the dressing table, in antique boxes and holders.

"You're neat," I observed.

She looked embarrassed. "Yeah."

On the couch in the huge bedroom were some dresses with the tags still on that she'd bought at Ohrbach's. "Isn't that cute?" Barbra said, holding one up. "Like a school uniform. I'm going to wear it with knee socks and flat shoes. They each cost $17.99. It's crazy. I'll buy a Galanos dress, $750, wool, and then I'll go out and buy all these dresses for $17.99. Let me show you my favorite room."

We went into a room that had nothing in it but Barbra's clothes; one wall just for dresses, one wall for shoes, one for bags and accessories. Everything was immaculate. Many Beverly Hills mansions have the same arrangement, but it's still the one thing, to my mind, that speaks of having arrived. For a girl, it's a dream room.

"Mommy's clothes," said Jason. "Yes," Barbra said happily. "Mommy's clothes." She seemed much prouder of his sentence than of the clothes or the room. She picked Jason up and stood in the doorway. "Your hair is the same color as the baby's," Horowitz ob- served. "Does she or doesn't she?" "You know she does," Barbra said.

She put the baby back in his room and we went downstairs, where Barbra circled the living room, seeing that everything was ready for her dinner guests, wondering where all the ashtrays had got to. She had a sotto voce consultation with her housekeeper. I eavesdropped, of course.

"I have these two bra slips that split when they were washed," said the star who makes a million dollars a picture, "and I thought we could cut off the slips so I could still wear the bras and they wouldn't go to waste."

A minute later, I said that since her guests would soon be there I should leave. "Oh, no, you have to taste the ice cream first!" She took me into the kitchen.

Strange, exotic Chinese food was laid out on the butcher's- block table, ready to be prepared. "I used to work in a Chinese restaurant," Barbra said. "In 'Takeout.' " She rattled off some Chinese. "That's 'sweet and sour pork.' " More Chinese. "That's 'eggroll.'"

She gave me a dish for the ice cream, but we both ended up eating it out of the paper containers with two spoons— licorice ice cream, peanut-butter-and-jelly ice cream, pumpkin ice cream. "Which do'you like the best? Here, try some more and decide.'" Then she ran over to the cabinet. "Taste this." She put it into my mouth: pickled scallion. "Try this—pickled radishes from Japan. Now we've had everything: pickles and ice cream."

A gift service had sent a sample: a mix of blue cheese and Roquefort rolled in a ball and covered with chopped nuts. Barbra had to open it and try it right away, so we had some of that, too.

"Wasn't that nice of them to send it!" she said. "They want an autograph," the housekeeper said. "Everybody wants something," Barbra said, and shrugged. I left then, with heartburn, and a very warm feeling for Barbra. "Goodbye." she said at the door. "Take care." But the way she said it, it didn't sound like a cliche; she really meant it. Our visit—and it really was a visit, not an interview—was all relaxed and simple. Barbra Streisand really is a nice lady. If she weren't so talented and such a star and didn't say such kooky things, nobody would bother to write about her. But they would be awfully glad they had met her and spent time with her. I was.

Sadie, Sadie, married lady, you can come to my house and eat hazerei any time!

End.

[ top of page ]