January 1966

Cavalier Magazine

by Alan Levy

[Barbra-Archives Note: The article which appears below was excerpted from Cavalier Magazine in 1966. I did not include the first two pages in which the writer quoted various interviews with Ms. Streisand which appeared in other publications. Since most of the material is redundant, this excerpt begins with the new material: an interview with Barbra in her FUNNY GIRL dressing room...]

Barbra's dressing room at the Winter Garden was empty of people when I was admitted. But it was by no means empty. It was cluttered with photos, paintings, posters, and clippings of Barbra; enough toy pigs and penguins to stock a concession at Coney Island; a portrait of John F. Kennedy; piano, TV set, and refrigerator; bouquets of paper flowers; a collection of ornate fans; and a shelf of books featuring Your 1965 Solar Horoscope, How to Raise a Dog, Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman, Dead Souls by Gogol, Mrs. Richard Rodgers' guide to decorating and entertaining, Let's Peel an Onion, a series of essays on extrasensory perception, The Children's Shakespeare, Reason in Society by George Santayana, and a paperback sequel to Famous Monsters of Filmland. This one was called Son of Famous Monsters of Filmland. A chaperone from Barbra's press agency, who had followed me in, explained, "Barbra loves pigs, penguins, and horror movies. She says penguins are like little men."

The dressing room was like no other I have ever seen. First of all, it wasn't just a room but a two-room suite (living room and dressing room, plus a lavish John) with red and green wall-to-wall carpeting, a florid wallpaper whose style struck me as $1.19-steak-house Paisley, 15th-Century Directoire chairs, a Louis XIV daybed, and, above all, a huge crystal chandelier. There is some talk that, after Barbra leaves Funny Girl on December 26, the dressing room will be maintained in its present form as a Museum of the Performing Arts. A visit there has already become part of New York City's welcome for heroes, along with a ticker-tape parade up Broadway. When visiting astronaut Scott Carpenter, just back from Outer Space, dropped up, he was greeted with Earth Mother aplomb:

"I'm really honored. I'm always interested in scientific and medical things. Whenever I go to the dentist, I can spend three, three-and-a-half hours there talking about nerve endings and things like that." While I browsed, a girl in a red polka-dotted muumuu breezed in, said "Hi!", and busied herself with a live white toy French poodle on a leash. The poodle, name of Sadie, was unmarried. The girl, name of Barbra, took some dog food out of the refrigerator and told me to "siddown" while she coaxed Sadie to eat. Sadie didn't need much coaxing, but the brief flurry of household activity had a warm, comforting effect. The absurd dressing room, which had made me feel like a pawn adrift on a Mad Hatter's chessboard, took on a flavor of Jewish matron gemutlich. My hostess was as real as food—a young, attractive house-wife, not a caricature and certainly not a sex symbol in a muumuu (Barbra's addiction to wearing tents impels columnists to color her pregnant. This worries her: "Maybe they know something I don't know.") Her bustling around put me at ease. I was no longer an interviewer, but more of a casual caller—perhaps a nice young man who had come to sell her an Encyclopedia Britannica that she really didn't need, but would like to hear about. Except, I reminded myself, my hostess already is an entry in the Britannica Yearbook as one of the prime tastemakers of the 1960's. The introductions were only mildly strained. "I'm shy," she confessed. "Like I can't say my own name. I can't say 'I'm Barbra Streisand.' It's a hard thing to say your own name, y'know?" (Which may be one of many reasons why Bernie Schwartz becomes Tony Curtis, Rosetta Jacobs becomes Piper Laurie, and Betty Peiske becomes Lauren Bacall.) Barbra was not shy, however, about discussing herself. "What have you found out about me?" she asked with genuine concern.

"I'm really honored. I'm always interested in scientific and medical things. Whenever I go to the dentist, I can spend three, three-and-a-half hours there talking about nerve endings and things like that." While I browsed, a girl in a red polka-dotted muumuu breezed in, said "Hi!", and busied herself with a live white toy French poodle on a leash. The poodle, name of Sadie, was unmarried. The girl, name of Barbra, took some dog food out of the refrigerator and told me to "siddown" while she coaxed Sadie to eat. Sadie didn't need much coaxing, but the brief flurry of household activity had a warm, comforting effect. The absurd dressing room, which had made me feel like a pawn adrift on a Mad Hatter's chessboard, took on a flavor of Jewish matron gemutlich. My hostess was as real as food—a young, attractive house-wife, not a caricature and certainly not a sex symbol in a muumuu (Barbra's addiction to wearing tents impels columnists to color her pregnant. This worries her: "Maybe they know something I don't know.") Her bustling around put me at ease. I was no longer an interviewer, but more of a casual caller—perhaps a nice young man who had come to sell her an Encyclopedia Britannica that she really didn't need, but would like to hear about. Except, I reminded myself, my hostess already is an entry in the Britannica Yearbook as one of the prime tastemakers of the 1960's. The introductions were only mildly strained. "I'm shy," she confessed. "Like I can't say my own name. I can't say 'I'm Barbra Streisand.' It's a hard thing to say your own name, y'know?" (Which may be one of many reasons why Bernie Schwartz becomes Tony Curtis, Rosetta Jacobs becomes Piper Laurie, and Betty Peiske becomes Lauren Bacall.) Barbra was not shy, however, about discussing herself. "What have you found out about me?" she asked with genuine concern.

"There were these two baby girls playing in the sandbox at the park," I began. "And they're named Barbra without the middle a."

"No kidding," she said. "I'm flattered. I made the name up, know what I mean? So it's nice. I mean, that's what any performer hopes to do—to make some sort of dent on people." We chatted about a generation of little boys named Adlai growing up on the Grand Concourse and getting ready for Bar Mitzvahs now. A nice tribute, we agreed. And we talked about several generations of girls and women striving desperately for the Barbra look. I mentioned a case of mistaken identity in which Sidney Skolsky interviewed Barbra, departed, realized he'd forgotten to kiss her goodbye, went back, and kissed the wrong girl.

"That's his problem," said Barbra. Mostly, she is flattered by her imitators. But then she went on:

"The ones I've seen that struck me the most—with the eyes out to here and the hair down to there—had a look of depressed rebelliousness. They're not like joyous girls. Everything's closed in. It's written all over them that, if I made it, they can make it, too.

"I feel sorry for them. Their pride is in their rebellion. I mean, I didn't rebel just for the sake of rebelling. Also, I had a sense of humor that led me outta many traps. What I mean is: If you only have the depression without the humor, what have you?

"People write to me and say, "You're just like me, so could you help me?' And I'm tempted to say, 'You're not just like me. You're asking for help. I never did.' "

"How do you cope with requests for advice?" I asked. Her answer was a shrug and, "Who am I to give advice? If it's not your own thought, it can't solve your own problem." We discussed a Chinese custom, whereby you become responsible for any life you save, and she conceded that she has to be very careful about "leeches." And about abusing her power. A newspaper recently asked her for some advice to girls who are thinking about having their noses bobbed. She declined emphatically.

"I mean," she told me, "it's such an individual thing. If your nose is ruining your life and you think a new nose will make you desirable, by all means have a nose job." Then she volunteered her own opinion: "Most nose jobs are terrible. They look worse than the original. They take skin off and make your nose look false - like a pig! And the pain! And just think! One slip of the knife! It's like defying God! It's like defying Nature!" Now she was every inch the impassioned actress, and I wondered how she'd follow such a speech. The answer was like comic relief.

"Where's Sadie?" Barbra asked.

"She was around a minute ago, eating her dog food," said the press agent.

"She can't have gone far," I said.

"Yeh," said Barbra, "except somebody opened and closed the door for just a second while were were talking." With that, the foremost tastemaker of the 1960s got down on her hands and knees to crawl around the carpet and search high and low, mostly low, for Sadie, unmarried poodle. The press agent fell to the floor and so did I. We found Sadie underneath the day bed, where she was nasching a biscuit. We all stood up and watched Sadie eat. Barbra talked, as I knew that sooner or later she would, of food. Eating is still her most sacred ritual of the day. Not long ago, she went to Leone's for dinner: "The place was jammed and even though the food was great—listen, they brought us hot chestnuts after, which flipped me—people kept coming up in a stream all through dinner and saying the same thing over and over: 'Listen, I hate to bother ya, but willya sign this?' I wanted to say to them: "If ya hate to bother me, why do ya? Why don'tcha just admit ya know you're bothering me and don't care?' To be disturbed when you're trying to eat—that's awful!" Onstage, chanting A Sleepin' Bee across a crowded room or a jam-packed stadium, she involves us in her most intimate reverie—but she herself may be brooding about a recipe for ham with pineapple or a fried chicken TV dinner. The crucial quality to her is transmitting the emotional intensity of her involvement.

"This business is so porous," she told me. "Like one taxi driver who doesn't recognize me can spoil the whole dream. Acting and singing are never enough. You can't put your hands on them. You can't eat success." On the nightclub circuit, she used to disarm men-about-town who offered to buy her a drink by responding, "I'll have a baked potato instead. Hard crust and plenty of butter.... It was cheaper, wasn't it? And I was high enough in those days without liquor." Those who knew her then agree that her most eloquent performance was an acting-class improvisation of a chocolate chip melting in an oven. "It was beautiful, so tender," said an eyewitness. "We saw Barbra—not clunking around with big feet and bony arms—but as she felt in her imagination." Food fed her morale when nothing else did. Others were most impressed by her bravura performance on the TV special, A Date with Barbra [note: My Name is Barbra]. An Emmy took care of her morale on that one. Sadie abandoned her food and her mistress went back to her initial theme:

"Kids write to me that they like me because I'm like them. Because I reflect them! How selfish and egotistical we all are!"

"That annoys you?" I wondered.

"No, it doesn't annoy me. Because I realize it's a natural thing. I'd like to write back, though: Whaddya mean I'm like you? Who are you now? Do you have talent? Know what I mean? What have you achieved? I've worked and strived and struggled and attained, and who are you?" She turned to me and said softly, "If you printed this, it would sound terrible." But then her vehemence took hold again: "But why do they want to reduce me? I'm not that anymore. Why don't they qualify what they say? Why don't they say, 'Barbra, you used to be like me.' I suppose I'm their wish fulfilled."

As a nobody, Barbra herself used to "identify" with Marion Brando: "I wanted to say to him: 'Let us speak to one another because I understand you. You are just like me.' A few years later, when she was Somebody, she and Brando finally met and, as she recalls it, "What the hell was there to say?"

Another early hero was Frank Sinatra and, at their first encounter she was so awed that she stood up whenever he entered the room. Now she receives fan mail from him ("You were magnificent. I love you.") And the reversal of roles may be complete when and if she ever co-stars with him in a screen version of Funny Girl. The deal was in negotiation at the time of my visit, so no comment was forthcoming on a story that Barbra insisted on being billed ABOVE her hero. Upstarts have been beaten for lesser heresies, but Sinatra, the story goes, patiently explained that this could never be. And Barbra is supposed to have countered with three virtually irresistible arguments:

1. "Well, I'm a girl."

2. "Well, it's my first movie."

3. "Well, you oughtta."

Consult your movie marquees many months hence for the ultimate outcome.

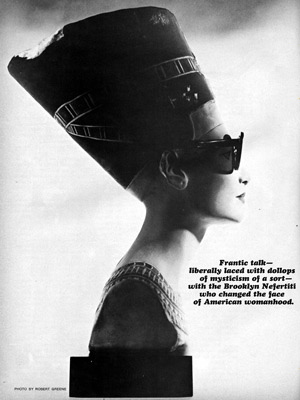

Barbra also receives fan mail from Audrey Hepburn, who cabled her: "YOU ARE WONDERFUL, MUCH MORE WONDERFUL THAN YOU CAN IMAGINE." This prompted one waspish commentator to complain that Barbra has done to American standards of beauty what Audrey almost did to bosoms and what Julie Andrews may yet do to chins: Drive them out of business. Or, as Barbra says in Funny Girl, "D'ya think beautiful girls are gonna be in style forever?"

I told Barbra about my latest parlor game—which I play in the interests of research as well as small talk: At parties or on street corners, approach the most gorgeous female in sight and ask, "What do you, as a conventionally beautiful woman, think of Barbra as an influence on American beauty?" You will never elicit a bland "No comment."

The answers had been mostly favorable, with one straddle ("How can you ask a woman to denounce what she's doing to herself?") and two notable dissents: "The Barbra Look is the latest joke that the faggots have put over on American women," a struggling model insisted. And a starlet said to me, "A woman comes out of Funny Girl saying to her man, 'Isn't she great! But what she's saying to herself is, 'That's the most glamorous female in America— and I'm better-looking.' "

Barbra drew in her breath and said, without much anger, "People must justify my success. They need to gain security at somebody's expense. I mean, if you look at her hard enough, maybe Elizabeth Taylor isn't as beautiful as she's been made out to be. Her nose isn't perfect, and she needs to be photographed at three-quarter profile. And her eyes aren't really violet. Personally, for beauty I prefer Silvana Mangano. But why can't people submit to the fact that Elizabeth Taylor is pretty damn beautiful. Or that I am what I am?"

"And the people who write about Barbra," the press agent added protectively, "they have to tear her down first before they put her on a pedestal. They think it makes more of a Cinderella story that way."

"The American people," said Barbra, "are preoccupied with one kind of face, and this is all that beauty means to them."

"A Dolly Dimple face?" I asked.

"More like Shirley Temple," she replied. I expressed my surprise at how calmly Barbra has withstood the descriptive epithets that come her way. It is easy enough for a woman to deprecate herself (Barbra has labeled herself an "ugly duckling" and "nobody's idea of an ingenue") and then pause one beat to allow the protests to register. It must be hard, however, to pick up the New York Times and see yourself described as "a pushcart broad" and "too damn delicatessen."

"They're starting to get through to her," the press agent told me. "Every now and then she winces."

Barbra alluded indirectly to the damage a stray metaphor can inflict on the toughest psyche:

"I wish my mother would believe I've made it. She wanted me to be a clerk or a teacher, something conventional and solid, and she doesn't believe any of this. When she sees something bad about me in the papers, like, for example, that I have Fu Manchu fingernails, she seizes on it as proof that all the rest isn't real."

I glanced at her nails. They were long and sharp, but not talons. They were the nails of half the girls in New York-only cleaner.

The pit band for Funny Girl was tuning up the music that makes her dance and it was time for Barbra to shed her muumuu and be wired for sound. (Although she can belt as loudly as Ethel Merman, she wears a microphone in her cleavage to deliver the low throbs to the balcony. The batteries are taped to her bottom. One memorable night, her equipment began receiving and transmitting police radio calls to the audience of Funny Girl.) Her press agent started to lead me out of the dressing room, but Barbra wasn't quite finished:

"If I were this strange-looking creature I got known as, I could never play a love scene on the stage. Who'd pay to watch someone kiss a girl who's homely or fat or badly built or with bad teeth? But I'm nothing like that. The first thing women say who come backstage after the play is, 'Oh, you're too pretty for the part.' And men from Italy, for instance, are shocked when somebody so much as hints that I'm anything less than beautiful. Like Marcello. He not only says my face is beautiful, but that it's my most important asset because - I - don't- look - like - anyone - else!"

On my way out, I picked up a program for Funny Girl and read Barbra's authorized biography:

"A top recording star, a talented interior decorator, dress designer, and portrait painter, she also plays field hockey. Her performance in I Can Get It For You Wholesale stopped the show and was much admired by the critic, David Merrick, and the show's leading man, Elliott Gould, who married her. Barbra is a follower of Eastern philosophy and cooking, but also favors TV dinners on occasion. . . . Her favorite day of the week is Tuesday, since she devotes part of each Tuesday throughout the year to stringing crystal beads which are sold in a Vermont general store. She knows how to make coffee ice cream and to fix her own hair. For more personal information, write to her Mother."

The line that intrigued me the most was the one about her being a disciple of Eastern philosophy. I wrote away for particulars. One day, my phone rang and an unearthly voice said, "She was an ardent Zen Buddhist until one day she lost the book."

End.

[ top of page ]