Business Week

May 20, 1967

What makes a Barbra special

Besides personality and charm, Miss Streisand has a manager who limits her appearances. One result: Monsanto is delighted to pick up a six-figure bill for her next TV show

Her name is Barbra. Her second name, of course, is Streisand.

One evening next October, this performer who needs little introduction will be featured in a taped, hour-long "special" program in color over the CBS television network. Titled The Belle of 14th Street, the show will attempt to recreate authentic vaudeville entertainment of the pre-1914 era. Co-billed as guests of Miss Streisand will be actor Jason Robards, veteran song and dance man John Bubbles, and dancer Lee Allen.

If the program does as well as the two earlier Streisand specials, over 20-million people will be tuned in—and new popular and professional acclaim will be paid to the 25-year-old girl from Brooklyn who has strained the hyperbole of press agents and reviewers in her flight to the top of the entertainment world.

Paying the tab. Among the most delighted by her show this fall will be Barbra's TV sponsor, Monsanto Co.'s Textiles Div. (formerly Chemstrand Co.), which sponsored the first two specials, My Name is Barbra in April, 1965, and Color Me Barbra in March, 1966. Monsanto has spent an average of $580,000 for each of the three programs and feels it has gotten its money's worth in advertising and publicity for its synthetic fibers.

The network, which acts as middleman, is just as convinced of the value of its investment. It is paying a minimum of $5 million over 10 years to Barbra's independent TV company, Ellbar Productions. This comes to around $500,000 each for one show a year.

"That's sufficient," says Martin Erlichman, Barbra's 36-year-old manager and chief strategist. "I like to think of her specials as really special."

Out of the Village. In 1961, Erlichman found Barbra doing an offbeat singing act in a Greenwich Village night club, and he is given a great a deal of credit for what has happened since: her appearances on nighttime TV shows (where she gained a reputation as an outspoken "kook" that she has been trying to shake); her first musical comedy part, which established her, in I Can Get If for You Wholesale; her outstanding recording sales; her TV career; creation of the role of Fanny Brice in Funny Girl; and personal appearances around the country, before two Presidents, and in England.

At present, she is in Hollywood and about to burst into motion pictures. She has agreed, at an unprecedented price for a newcomer, to film Columbia Picture's version of Funny Girl, Twentieth Century Fox Film's Hello, Dolly!, and Paramount Pictures' On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.

I. The right material. To a greater degree than most celebrities, Barbra has succeeded by picking "quality" shows and avoiding overexposure. This was necessary to set off her unconventional gamin looks, her arresting voice — and the Streisand mystique, which contains elements of adolescence, hipness, and folksy humor.

Discussions about this fall's special, for example, began a year before videotaping, which took place last month, in New York. First came conversations involving Barbra; her husband and associate, actor Elliott Gould (the first part of Ellbar); Erlichman; her TV director, Joe Layton. and writer Robert Emmett.

Good old days. In her antique-decorated, Central Park West apartment before the taping, Barbra explained: "We came up with the idea of doing a real, turn-of-century variety show with the songs and costumes of that time . . . We weren't looking to make fun of it, or 'camp' it, but do it as they did."

There followed weeks of research in old tomes on show business, back volumes of Variety, and listening to recordings of old performers such as Eva Tanguay. "We even called George Burns in Hollywood and Jack Pearl," says Erlichman, naming two living survivors of vaudeville.

Things slowed down toward the Christmas holidays when Barbra's first child, Jason Emanuel, was born. Then, after a period of maternal retreat, conferences on the show resumed in earnest early this year.

Guest stars were lined up. It had been decided that, unlike the previous specials which were showcases for a relatively new TV performer, 3 other name performers would join Barbra in this one.

Format. As eventually put together, the program was to have eight different routines, including: a rousing, patriotic number with Jason Robards, Barbra, Lee Allen, and a pert 11-year-old child performer, Susan Alpern; a tear-bringing refrain, Mammy o' Mine, by John Bubbles (the original Sportin' Life in Porgy and Bess), and an 11-minute, quick-change version of the Tempest with Barbra and Robards.

Barbra also would do a series of solos, as the headliner, the Belle of 14th Street herself; as a German lieder singer; and as a boy soprano — plus a striptease number, billed as an Unforgettable Forget-Me-Not.

For sheer pulchritude, though, the bravos would go to a line of heavy-weight chorus girls, each weighing in at over 200 lb., and decked in fluffy, pink frocks. Nicknamed the Beef Trust Chorus, they were chosen in a contest that drew considerable publicity and were modeled after a real act of the 1900s. "In the old days," comments director Joe Layton, "everyone had a gimmick."

Progress reports, as the book took shape, were made to CBS, the sponsor, and the sponsor's ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach. This was chiefly to inform and satisfy curiosity rattier than to seek approval: Streisand's contract provides for absolute creative control. Her company delivers its packages to the network for the agreed-on price, and pays all production overhead, including crew costs, studio rental, and talent fees.

Period-piece audience. The sponsor was gratified in other ways however. About 120 of Monsanto's primary and secondary customers in the textile-apparel trade were invited to play the audience — in period costume — for this simulated variety show. Their fee was the kick of applauding on camera, watching the cast put on a few numbers, and a party to top it off. They were asked to appear at the studio only on the last day of taping, but through clever splicing, it would appear that they were there during the entire show.

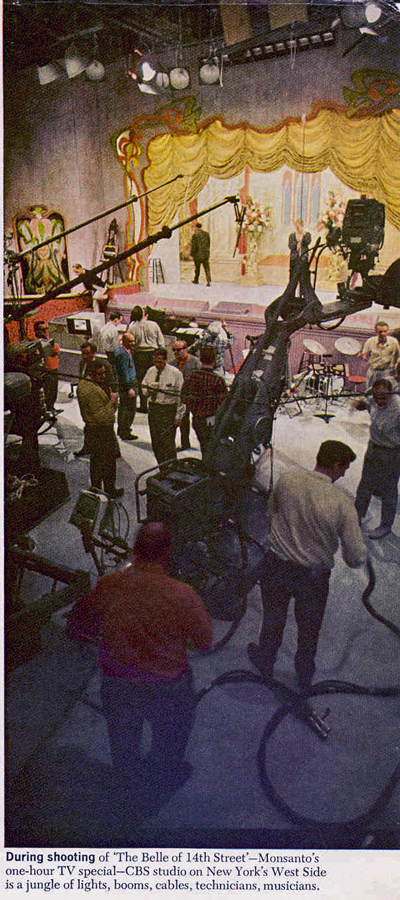

Videotaping took four days, Apr. 26 through 29, on Manhattan's West Side — in CBS's enormous studio 41, crowded with camera cranes, boom mikes, cables, and banks of lights and catwalks overhead. Sometimes until early morning, this studio also was filled with people: 150 behind-the-scenes technicians, extra actors, publicity agents, photographers, hairdressers, wardrobe and makeup attendants, CBS guards and pages, and representatives of the network, sponsor, and ad agency. Most not immediately involved in the production watched from the edges of the set, or peered down from a narrow balcony facing the stage.

The set was a slightly art nouveau interpretation of a variety house stage, circa 1900. The orchestra pit was occupied by only eight mustachioed musicians and a conductor, because musical accompaniment was played back from a tape prerecorded by a 28-man orchestra.

II. Over and over. What impressed observers the most was that making the one-hour TV special was precisely like making a small movie. There were numerous "takes" and retakes of scenes, until on-stage fluffs or technical problems were eliminated. This was engineered from the multi-screened and dialed control room, where Walter Miller, the technical director, fired cues to cameras.

Some of the interruptions resulted from mishaps. During the patriotic number, Jason Robard's trousers were taken away for unexplained repairs, and he waited in his shorts, coolly puffing a cigarette until they were returned. Barbra, playing Ariel in the Tempest, also had some faulty landings until she mastered flying on a wire and harness. "At least you could pick me up," she said to the director after one leap.

The most trying moments came during her striptease, in which stagehands pulled off Barbra's "breakaway" dress by wires, a section at a time, leaving her clad in a lavender, satin corset. The elaborately hooked-together gown didn't fall apart correctly until 5 a.m. Halfway through that night, director Joe Layton tossed himself down in a control room chair and announced; "I'm going to a sanitarium, I had to be crazy to do the Tempest and a breakaway dress in the same show."

Premium. He made the comment with an eye on the clock. The more overtime, or "golden hours" as they are called in the trade, the less the show's profits. Even the absentee musicians, whose efforts were on the soundtrack, received double pay after midnight. "We don't make much," says Erlichman. Frequently the real money made by specials comes from second showings and foreign markets.

Despite the slow pace, nearly all the numbers were done in time to receive the audience on Saturday, the last day.

Gala affair. By 11pm, the last sequence of the Belle on 14th Street was taped, and the only things that remained were a couple of weeks of splicing for the directors and technicians, some extra notes to be tracked in, and a lavish party hosted by Monsanto. The costumed trouped of over 150 was driven downtown to Luchow's on 14th Street, a favorite eating place of such gaslight-era stars as Lillian Russell. And obviously good time was had by all (Barbra and her husband were among the last to go home).

"We're proud of this one," beamed George McGrath, Monsanto's ad director, speaking of the celebration. But he could have been referring to the TV production as well.

III. Making it pay. In the next few months before the show runs (on an evening to be selected between Oct. 17 and Oct. 24), Monsanto will be promoting its investment as hard as it can. The company has two audiences in mind: Naturally, it wants many people at home to watch; its specials are timed for peak retail sales periods. But just as important, it plumps the wholesale trade about the coming show and makes sure the pipelines are filled with Acrilan or Cumuloft nylon carpets, and apparel under Monsanto's Wear Dated and Actionwear programs.

"This has a terrific effect on the trade," says Robert Born, marketing director. "We try to get our money out by the time the show is put on."

Altogether, Monsanto is putting on six TV specials this year, of which Barbra's is one. Others, some of which already have run, are by Dick Van Dyke (also on CBS), and Zero Mostel, Sophia Loren, and Carol Channing (all ABC). This makes Monsanto one of the largest purchasers of specials.

Looking Ahead. Because Monsanto wants to maintain identity with Barbra and its other special stars, it is "assiduously" trying to obtain the next Streisand show, now in early planning stages. This one will be an outdoor concert to be taped in Central Park for 1968.For her part, La Streisand has been happy with the sponsor. "They've been great. You show them the show, and it's done ... And I don't have to go around and appear for them at places. That's harder than performing."

Actually, Barbra has engaged in extra-curricular appearances. She has made a trailer film about the forthcoming show to be shown to Monsanto customers and retailers. Also, after her second special last year, Monsanto sent her on a free trip to the Paris couture collections where she obtained a Dior wardrobe, daily news attention, and several magazine cover stories.

But despite this, and being named to the best-dressed list in 1965, she confesses she still likes to drop into stores and buy inexpensive clothes, or "shmatas," as she calls them in Yiddish. "It all goes back to my frugal ways," she says modestly.

IV. Superstar's rewards. Meanwhile, the reward for her success seems to be more work. After finishing the special, she flew directly to Hollywood. There she has rented Greta Garbo's former home and is now rehearsing for Funny Girl, which is slated to start production July 5.

Strategy. Her manager, Erlichman, looks at Barbra's future this way: "Barbra is a $100-million business." He computes her earnings capacity at $3-million to $4-million a year and says, "I think she's going to be around 30 years."

He doesn't want to overexpose her in any one medium, though. "If she does one special a year, six to eight weeks of personal appearances, and her recordings, that's enough." As an annuity besides, Barbra, her husband, and Erlichman have set up a complex of interlocking companies under another compound name, Barbel Enterprises. Barbel generates income publishing sheet music and books, and by producing TV and stage shows featuring other performers.

There are also the tapes of the specials, which can fetch $500,000 for re-runs. But her manager is keeping these in the bank. "Someday," he envisions, "there will be TV cartridges that you can play at home...and I also look forward to a time when they may have a Streisand week."

END

Page credits: Pictures courtesy Craig Dickson, from his collection.

Related: The Belle of 14th Street TV Show