After Five

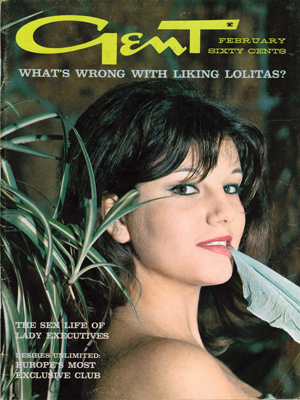

[Gent Magazine, by Mack Curtin]

February 1964

The circle of light picks her out and immediately the audience is aware of a separate force. Her long elegant fingers jab the air with overlong pink fingernails. The diction is almost affected but absolutely clear. The opening song is over nearly before it begins. There is then time for mutual appraisal. Hers of the audience and they, more closely, of her. Formalities are off-handedly dispensed with and her second song begins. It is somewhere in this song that the audience becomes pleasantly aware that it has submitted to latter-day witchcraft. Its practitioner gives no sign that she knows or even cares, because she is telling them the most important story in the world and she has never told it to anyone before. When her song is finished, she chatters on amiably, either about her dress or how her hair looks or how she happens to feel on that particular night. All is received by the audience with an attention so fixed that a practicing hypnotist would sallow with envy.

Generally at this time she interjects lighter material. Often alarmingly brief, such as “You better not shout, You better not cry. You better not pout, I’m telling you why — Santa Claus is dead.”

It is, however, in great numbers such as “Cry Me A River” or “Happy Days Are Here Again” that she reaches most deeply into her audiences. It is here that her abilities as an actress, above and apart from her capacity to entertain, raise her songs to the level of actual experience for her listeners.

At the end, the applause is always closer to an ovation and the audience leaves in a strangely contented mood because for a brief time, they have been taken out of themselves, drenched in both sorrow and hilarity and then calmly revived and sent back to their own lives.

Barbra Streisand, at the age of 21, bears the stamp of a true “original” — the most precious attribute a creative artist can possess. In the world of popular entertainment, originals do not appear frequently. When they do, they have, without exception, been great stars. They may not have any one talent which cannot be found in greater degree or more perfect form, in lesser-known artists. But they all, however, have been able to project the ineffable radiance known as “star quality.”

Anyone who has seen Miss Streisand perform or heard her Columbia recordings realizes that “star quality” is a term with a very real meaning in her case. Her nonchalant manipulation of her audiences has caused more than one show business veteran to shake his head in disbelief. It is difficult to attend a Streisand performance. One participates in it.

She has been compared, among others, to Fanny Brice, Beatrice Lillie, Lena Horne, in fact to almost everyone but Jenny Lind. In some degree, it is easy to see why people insist on comparing her to other artists. There is something reminiscent about her performances. Actually what occurs is that she agitates a seldom-plucked cord within everyone. That cord is a palpable and visible excitement generated only by those artists in full command of all about them; by all great performers, be they dictators or divas. How few there are is obvious in the number of highly paid and publicized performers who with $25,000 acts, bevies of chorus boys and/ or girls, special arrangements, masochistic conductors and four changes of costume, proceed to reduce their audience to a state of quiescent-alcoholism by the blandness of their efforts. They are extremely proud of the “newness” each year of their material, their act, their costumes, and most of all what they fondly introduce as “my newest hit.”

On the contrary, the true original changes from year to year about as much as Ethel Merman’s hair style or Edith Piaf’s collection of little black dresses. There has been about Barbra Streisand, from the very beginning, this sureness of approach. To the end, her most compelling focus will remain her hands, her hair, her eyes and a purple grab in her voice.

Miss Streisand’s Broadway debut in Harold Rome’s “I Can Get It For You Wholesale” in the 1962-63 season served notice that not since Mary Martin had arrived on stage in the late 1930’s, perched on a cake of ice, wearing the briefest of parkas and declaring a prurient affection for her Daddy, had any performer so immediately and completely established herself.

Barbra Streisand represents, to many, the outsider looking in. An outsider perhaps by choice; by her refusal to accept a commonplace set of values and willing to pay the price. Not a beatnik, but not committed either. Willing to be something that has become increasingly difficult — an individual. She speaks for a whole group disenchanted by the joys of conformity; a prematurely aged youth that may not be sure what it wants but has a fair idea of what it does not want.

Barbra Streisand is a kook!

But is she? As remote from the average night club performer as Arnold Toynbee, she is currently the most sought-after performer in this cruelly realistic field. Most of her material is unfamiliar to the mass public, yet she is the single most important new female recording artist. She has appeared in only one Broadway show, in a feature role, but the choice is hers of what will be her next play.

Performers as universal as Barbra Streisand come along very rarely. Once here they are seldom forgotten.

End.

Related Links: Funny Girl, Broadway Show pages