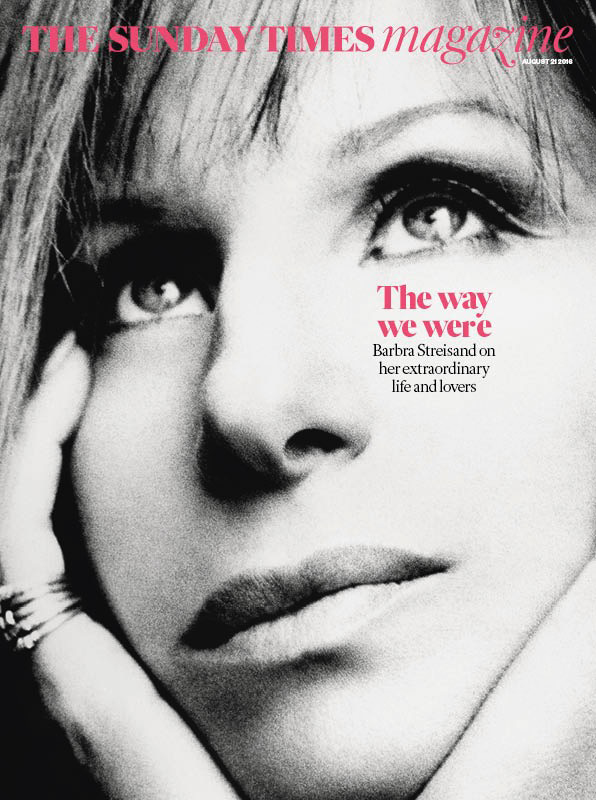

The Interview: Barbra Streisand, singer and actress

August 21, 2016

Interview by Chrissy Iley

I’m in Malibu. Not quite in Barbra Streisand’s house, but at a studio just down the road. She’s been doing some television interviews and the lights are set up, so bright that I have to peer to see her face.

I want to hug her hello. After all, this is Barbra Streisand, whose songs I’ve known all my life, whose voice is a comfort in its complete empathy. Whatever I’ve felt or whatever you’ve felt, Barbra’s songs make us believe she’s felt it more. That’s part of her charm, part of what makes her an icon.

My arms are already in a clumsy outreach when I remember her telling me in a previous interview that hugging doesn’t come naturally to her. She had a complicated relationship with her mother, Diana, who always discouraged her from pursuing a career in show business, perhaps out of fear that her daughter might fail. She told her that her voice was too thin. Diana was an amateur soprano with professional ambitions. They never hugged; her mother wasn’t a toucher, so “for a long time, touching felt alien”. Now she can just about do it — touch, that is. Still, Streisand could never please her mother. “But I owe her my career. I was always trying to prove to her that I was worthy of being somebody,” she said when we last met.

She is 74. There’s less angst about Barbra now, more composure, more polish. She’s wearing a soft, drapey black dress, multiple long gold chains and strappy sandals that have spikes across the straps. Dark red toenail polish. The feet are very maîtresse — dominatrix, even, though the rest of her is soft. She’s always loved the juxtaposition of feminine and masculine.

Instead of a hug, I deliver her a cake, one made from the recipe used by her favourite childhood bakery in Brooklyn (Ebingers, which closed in 1972). My friend’s grandmother was the manager, and he has all the recipes. It’s a mocha almond cake and more powerful than a hug or a kiss. To Streisand food is love.

She’s always loved food a little too much — always on a diet — although she’s never been fat. I’ve heard she once used a cake on stage to make her cry. “That’s right,” she says. “It was a chocolate cake and it was put on the stool [in the wings] where I could see it. It wasn’t that I had to cry,” she corrects. “It was that I was supposed to be in love with the actor but I couldn’t feel anything for him. I didn’t even like him. I put the piece of cake in the wings so I could pine for the piece of cake.” We laugh. A real, proper laugh, the composure gone.

Streisand is never afraid to be herself. I remember the story of when she was asked to play the film star and Broadway comedian Fanny Brice in Funny Girl. Brice had had a nose job in real life. “She cut off her nose to spite her race,” Dorothy Parker quipped in 1923. This almost cost Streisand the part. They worried that Streisand looked too Jewish to play a Jewish star with a nose job. She has always said she’d never change her nose.

What gets you about her new album, Encore, is its absolute Barbraness. I wonder if she’s improvised new words to the songs, they seem so her own. The songs are all rediscovered classics, recorded with unexpected artists including the actresses Anne Hathaway and Melissa McCarthy, and the Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane. There’s a soulful version of Climb Ev’ry Mountain with Jamie Foxx and an impressive duet with Hugh Jackman on Any Moment Now. There’s also a posthumous duet with Anthony Newley, a British singer-songwriter who died in 1999, on probably his most famous song, Who Can I Turn To?, which he wrote with Leslie Bricusse for the musical The Roar of the Greasepaint — The Smell of the Crowd in 1964. Newley, in his shaky Cockney tones, sounds like Laughing Gnome-era David Bowie. “I’ve heard that David Bowie was very influenced by Tony Newley. I was doing Funny Girl and he was doing The Roar of the Greasepaint, and I met him that year and thought he was fantastic. Then we became friends,” she says casually.

I tell her that at one point I was friendly with Sacha, Newley’s son with Joan Collins, and that we briefly worked on a musical about his father’s life. In the course of that I uncovered a little-known song called Too Much Woman. It was a song that Newley wrote about Streisand, whom, according to his son, he was completely in love with. Newley loved women, but for him Streisand stood alone as the unconquerable “too much” woman. Did she ever know about the song?

“Tony Newley sent it to me when he was dying and I thought, ‘Wow!’ ” She sings it to me in a Newley-style voice: “ ‘I heard you on the radio today ...’ It’s a wonderful song. I love that song.” Her voice is emotional now. She smiles. She wasn’t expecting me to know about it, but she seems far from floored by it, or the idea that he was deeply in love with her for all those years.

“Well, you have exclusive knowledge for your article, don’t you, because it has never been written about. I’m proud of that song. I’m proud that he wrote it for me.”

I understand the concept of “too much woman”, a strong woman, a woman in charge, a producer/writer/actor that isn’t a man. In the UK we have a female prime minister, for which both left and right seem grateful that she’s sensible. Is this a new age when there’s no such thing as too much woman?

“I don’t know much about your prime minister. She’ll probably have more balls than the old one,” she laughs.

Is Hillary Clinton too much woman for the United States? “I hope not. I really hope not, but I think the British have always been ...” Her voice trails off. “When I made Yentl as a first-time director, I made it in England,” she says, referring to her 1983 musical film, the first time a woman had written, produced, directed and starred in a major studio production. “Margaret Thatcher was prime minster and you had a Queen, so powerful women were no big deal. I think in this country we still think of powerful women as suspect, you know, like they’re too ambitious or they’re control freaks, which is such a shame.

“I pray that we will have Hillary as our president, and I think that informed, smart people are going to vote for her. At least I hope so. I’ve met a lot of people who are powerful and smart, like Michelle Obama.”

On the day we meet, Donald Trump’s wife is accused of plagiarising portions of Michelle Obama’s speech from the 2008 Democratic convention. Streisand looks irritated. “They are that stupid?

“Golda Meir,” she says suddenly. “She was one of the first women to head a country [Meir was prime minister of Israel from 1969 until 1974, when she resigned]. I had a conversation with Golda Meir when it was the 30th anniversary of Israel, and that shows you all that women can be. She could declare war on one hand and say, ‘Would you like a Danish with the coffee?’ with the other. She was the grandma — a very warm, sweet lady, yet a powerful leader. Women can be many things: angry and forgiving; have PhDs and manicures.”

Streisand always has a beautiful manicure. A little defiant touchstone — her mother told her to cut her nails and learn to be a typist. I have no nails. She looks at my fingers a little mournfully, but it’s not about the nails. I was thinking we’d segue from Meir into hate crimes and what it means to be a Super Jew today, but instead she asks: “Can we talk about Newley some more? What happened to this musical? Why are you not working on it any more? Did you disagree?”

Not really. Sacha just went off me. “Why was that? What year was that? Is that why he was calling me and I could never find out what it was he wanted? I’ve met Sacha. He came to my house with his kid and his mum. The little girl wanted to see my dolls’ houses.”

Streisand has an annexe at her home where she keeps her collection of old-fashioned dolls’ houses. She told me once that she likes them so much because she didn’t have a proper childhood. As well as being constantly criticised by her mother, she was bullied as a child for looking too weird, too Jewish.

It was a painful sharpening of her drive. Her father, Emanuel, died from complications after an epileptic seizure when she was only 15 months old. She never knew him, but always missed him. She feels she found him while making Yentl, the story of a Jewish woman in the early 1900s whose desire to learn is so great that she disguises herself as a boy at a time when eduction was strictly a male preserve. Streisand played the film’s lead role. “I created him. I was the director: I was the one in control. I was the male figure. It was all very cathartic.”

She started off singing in clubs at about 18. In her first recording contract with Columbia Records she agreed to take less money as long as she could have full artistic control. Another time she clashed with her record company after her nose was airbrushed for an album cover. She has always fought for artistic integrity. “That’s right. That’s called a control freak, but why would any man or woman not want to be in control of their own life?” Now she belongs to a small coterie of luminaries who have collected Oscars, Emmys, Golden Globes, Grammys and a Tony.

I’ve never understood why so much has been made about her not looking like the perfect leading lady. When you look back at her in The Way We Were and Funny Girl, of course she looks striking, but also gorgeous. Perhaps it was because she didn’t believe she was beautiful that other people didn’t see the beauty in her. She carried around the sense that she was an oddball, a misfit, and because of that she became a champion for other misfits.

She tells me she’s happy with James Brolin, to whom she’s been married for 18 years. She’s been with her manager, Marty Erlichman, for 55 years, and with her assistant, Renata Buser, for 43. She at last has contentment.

Her first husband was Elliott Gould, whom she married in 1963. They have a son, Jason, now aged 49. They divorced in 1971. Maybe she was too much woman for him, too. This was after her performances in Funny Girl and Hello, Dolly!, and I wonder if he felt in her shadow. She brings the subject back to Tony Newley. He’s playing on her mind now. “He had a fantastic voice and he was so lovely and very handsome, yes. I loved his looks. He looked like the Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist.”

Streisand has always liked beautiful men. She told me once it was the one thing they all had in common. Warren Beatty, Ryan O’Neal, Don Johnson, Andre Agassi. “They were all attractive. I love beauty, whether it’s in a piece of furniture or a man. My husband has the perfect forehead, the perfect jaw, the perfect teeth. Even if he makes me angry, I get a kick out of his symmetry.”

She says happiness has changed her relationship with work — she’s become lazy. But work to Streisand is a very different concept from how it is to most people. She’s still prolific. She’s been working on her autobiography for more than a year. Right now there’s the album and a tour, and soon she starts work on the movie Gypsy, an update of the 1962 film about the burlesque dancer Gypsy Rose Lee; Streisand plays her domineering show-business mother, Mama Rose.

She has used her stardom well, raising so much money in support of women’s heart disease healthcare at Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre that it has named one of its cardiovascular units after her. These days it means more to her to have her name on the Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Centre than up in lights. More women die of heart attacks than breast cancer, yet more money is raised for breast cancer. Streisand is a lobbyist — she wants more funds. Coincidentally, her tours usually coincide with the run-up to an election. She is a Democrat, a campaigner with a passion.

She recently made a breakthrough by demanding that female lab mice be used for research into heart disease at the medical centre named after her. Apparently, mice used in drug trials were always male, even though the research was on women’s heart disease. “When I asked why, the answer I got was that female mice have hormones, so they’re more complex. Well, so are women,” she has said. “So even female mice are discriminated against!” She got her female mice in the end, but admits that “it was a fight”.

Fighting, though, is in her DNA. She always rises to fight for what she believes in. She has made me laugh, made me think. Would it be appropriate to hug her goodbye? Not really.

End.

Related: